|

(the natural world, the political context) :

collaborative monoprints by ghada amer and reza farkhondeh

by Vincent Katz

For weeks and weeks, two artists drew, painted, carefully selected papers, printed, layered, and analyzed. There are so many layers, and one would rather let them lie layered, not try to parse them. One would rather watch them work and observe that flux as a highly charged present moment, in which people are combining forces, conversations are quick and fragmentary, and the wishes of two artists are tried out, brought into being.

Ghada Amer grew up in Cairo; Reza Farkhondeh in Iran. They both studied at the Institut des Hautes Etudes en Arts Plastiques in Paris, at slightly different times, and met at the Villa Arson EPIAR art school in Nice when Reza arrived there in 1988. The main approaches at Villa Arson were based in Minimal and Conceptual art. Ghada’s memory is that students were not supposed to paint. Reza remembers that one could paint but that concept took precedence. He applied paint with gloved hands and remembers constructing an elaborate conceptual framework of questioning the paint as possibly dirty, a contaminated material from an older, oppressive culture, that one could handle only with safety gloves. Sometimes, there was such an emphasis on thinking that to make anything felt daunting.

One teacher at the school made a lasting impression on both artists: the poet Joseph Mouton, who told them simply, “Don’t think.” Providing this antidote to a program of rigid rules, Mouton encouraged them to do concrete things. Reza was affected by his teacher’s manner, calling it a “remedy” for the fear engendered in him by other teachers, and, one could add, not just those teachers but a larger intellectual environment of that time. Ghada was looking at America. The way Barbara Kruger’s work raised political issues — serious, but with a sense of humor — would influence her own treatment of political themes. Reza was making videos in art school: he admired Gary Hill, Bill Viola, Nam June Paik — artists who questioned the medium and aspired to image-making based on painting or sculpture.

Reza would find his way to painting, first making large-scale paintings of 99-cent items, then evolving into a non-representational treatment of plant imagery (he often constructs his images from built-up layers of masking tape). Ghada became known for her images of women from porn magazines, transformed by that most feminine of craft practices: sewing thread. Language has long played a part in her wry and sometimes very direct critiques of both Eastern and Western treatment and depictions of women.

*

The history of how they came to collaborate is essential to understanding their current work. They did not always collaborate but started separately and gradually decided to work together. It began when Reza painted on one of Ghada’s paintings. He was coming out of a depression. He thought his work was creating the depression and therefore had stopped working. What would happen if he did those bad things on Ghada’s canvases? He wanted to affect the authority she had created for herself as an artist. He began mixing colors, running up to her canvases, splashing, using tape.

He told her he thought the background of her painting was boring, and he would help her. And she thought he was right! She was confused and did not know how to react. He did not want to claim authorship. He would not sign the works. What he added would be a gift on her canvas. Only after one and a half or two years, did Ghada finally accept that they were collaborating and insist he sign the pieces.

Then they decided to work together on a new project in 2005, when they did their first collaborative drawings and prints. Ghada would interfere with Reza’s work, as he did with hers, and they would work together in prints. For Reza, this is important, because he perceives a gap separating their levels of success; Ghada’s work, according to Reza, is much more well-known and commercially viable. This would not be as significant in the print market, he thought. Prints, as often, provided a safe haven for experimentation and meditation.

*

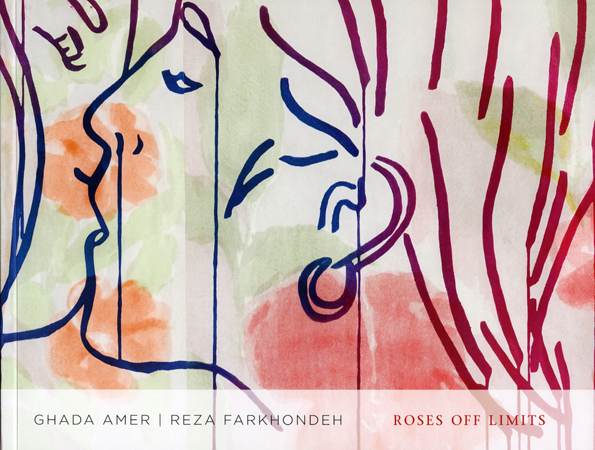

Ghada and Reza spent the summer of 2008 on a mind-boggling collaborative undertaking : a series of close to 200 monoprints. The workshop at Pace Prints became their studio, and master printers worked to enable their combined vision. In June, 2008, they brought drawings with them to Pace Prints and began to see what could happen. The resulting monoprints started from small drawings, sometimes enlarged via projection. They spent two months, working five full days a week, moving fluidly between — and combining — etching, drypoint, sugar lift, woodcut, linoleum cut, pressed paper, chine collé, fabric, sewing, and digital printing. At a certain point, after a period of trials, encouraged by the diverse printing possibilities at Pace and the printers’ willingness and ability to suggest procedures, patterns established themselves, and the two artists began to find systems for working.

A playful layering emerged: of Ghada’s erotic found images of women, often female couples, with Reza’s ceaseless patterns of leaves and flowers: an erotics of nature, of movement. The baffling array of techniques includes cutting of fabrics, taping, ghosting, projection, tracing, and transferring. The palette is consistently upbeat: bright, day-glo, colors indicate culturally non-specific good humor. Theirs is not, for all its combinatory fierceness, a collage technique. Their sophistication rather assimilates patterns and ideas from diverse periods and parts of the globe into their personal, present-tense, combined consciousness.

They took a break in August and came back for another month in September. At that point, as Reza put it, “There was no more blank paper.” Pieces were waiting for them — the results from June and July, which a month off helped put into perspective. The September process was working on work, always starting from a given field. “The whole process is editing” (Reza again). I wonder if that means anything gets taken out, but that does not seem often to be the case. It is more a case of adding elements until a balance has been reached. There is a file of unfinished works, and each one provides possibilities.

An observer can learn from the specifics of how the artists move from one decision to another. On one afternoon in September, Reza explains he is doing a test on a small plate, using 6B pencil together with solvent and ink. “The idea was to get the drawing back into the paper,” he says, retiring to a tiny room full of rags and colors. He quickly mixes a bright orange, pours it onto the small plate, tipping it from side to side to spread the solvent/pigment mix. It is an attempt to have the remaining graphite appear through the solvent, to see how they will react together. Reza has added another layer of ink to the small graphite test, to make it thicker. He will wait for it to dry, then print to see the result. He wants to find a different way of making a wash, without using a brush. If this test works, he may be on his way. The desire to remove the trace of the brush reminds one of the gloves at Villa Arson.

Each piece is a little different from the others, but many partake of common experiences in the print studio. Reza explains they all get a translucent wash that helps support the other images as they get added in. We look at another print, in an initial stage: mylars with white vegetal drawings. He is trying to get as much translucency as possible transferred to the opaque papers that will form the supports of the monoprints. In this case, there are four different patterns that have been transferred to four different plates that will be layered.

In the main room, another sheet is being pulled. Each sheet is always a step, a possible link to yet another way of bringing forth an image. The freshly-pulled sheet is orange in tonality with flowers and other vegetational designs. Ghada arrives. “Just on time, huh?” she says to Reza. “Just on time,” he agrees. Now they will work on the ghost. There was one that was white, and one that was not so transparent. Some talk about which ghost on which paper. These discussions among printers and artists, printers facilitating artists’ desires, forge not a clear path but an approach, since the artists are planning and mixing simultaneously. All is done in good humor, but the jokes frequently give way to serious discussion, much like a discussion on which path to take, if a group were on a hike in the woods.

Ghada will now go to paint on a plate. She paints on it in a focused, consistent, manner. The image is an idea to guide her, and her hand simply follows that. Sometimes drips of paint fall from her lines, and she leaves them there. They are arbitrary designs, created by the process, like the lines of thread that form thickets in her paintings around, or in spite of, the drawn images.

It is exciting to watch the printers sewing into paper: a loud pop as the needle punctures the paper, a pulling sound as the thread is drawn through; a repetitive, cumulative effort. Ghada has used sewing throughout much of her career, both as imagery and political subject matter. Viewers of her work have been made to contemplate the implications of a woman’s wielding a needle to her own ends. She is still the person in control of the needle, only now it is a different hand that works the domestic instrument at her instruction. Ghada often uses stitching in her paintings and drawings. It has become so identified with her work — her “trademark,” she jokes — that people expect the stitching to identify her work. Those expectations can be burdensome — to her and to the collaboration. For that reason, the number of pieces including stitching in these monoprints is limited.

*

In the midst of this ceaseless activity, time is found to sit down and have a conversation. The question of authorship is fascinating; whose work is this? There is something seductive about being partially the viewer, not being the one to make all the decisions. How does collaboration relate to their individual work? When they collaborate, Ghada explains, no one mark belongs to one of them; all belong to both. Trust is a major element.

We talk about blurring lines, blending images and techniques. I want to talk too about subject matters, because those too are blending. We need to go back to talk about things that may have influenced them in the past. Where did the imagery that ends up in these pieces come from? Reza’s contribution comes in patterns of flowers or leaves. He is interested in how the flatness of his images can affect the decorative motifs. The idea of flatness, along with the flatness of the print, inspired him to the use of layers. He also wanted to look for translucent papers, papers through which light can pass. Each image on its own is precise, but with the layering of other motifs, the sharpness is softened a little, as the image is forced to share space with others.

The images must collaborate, just as the artists have, if the work is to be successful. It is not clear that that will always be the case. In fact, of the close to 200 works Ghada and Reza created during their three months at Pace, they decided to keep roughly half. A certain number of experiments, useful in their own right and containing successful elements, were ultimately deemed by the artists not valid to become independent works of art.

Much of Reza’s earlier imagery dealt specifically with 99-cent culture. I wonder if his more recent reliance on plants signifies a different stance toward the world and what part of it to emphasize: the harsh, urban context of 20th-century mass production versus the grace of nature’s yearly rebirth. The motifs bring to mind Neapolitan painting, Islamic designs, medieval floral patterns. Was any of that going through Reza’s head? He mentions patterns on carpets and miniatures but says he does not work from specific references. He compiles an archive of images: some from his own photographs, others that he finds in magazines.

Combined with Reza’s flowers and plants are Ghada’s flagrantly erotic pictures. They come from pornography, but they become so delicate when transformed by her lines and effulgent colors that they seem no longer lurid but rather sweet. It is as though she has rescued the images (the girls themselves cannot be rescued) and brought them back their innocence. Still sexy, still posing, still pouty and provocative, they are now couched in the flowers and layers of two artists who love them. They are able to come out — to create an impact — but the statement is mollified. The repetition of an image plays a part in this. Pornography works because the viewer is tricked into thinking he has individual, personal, access to this girl (or boy). Here, we often see the same girl or girls repeated over and over, canceling the illusion of intimacy.

Ghada points out that she and Reza are from different cultures. She puts it delicately, saying that, as an outsider (she uses that word), not part of the Iranian culture, but knowing Reza for many years, she sees an Iranian cultural influence in his current work. Everything is a pretext to paint, she says, whether it be “Made In China” plastic toys or natural flowers. One subject is not better than the other to paint. “I am doing bodies and Reza is doing floral motifs,” she insists. “These are two major subjects in the history of art.”

Reza’s paintings of plastic toys were not cynical. They have a life-affirming quality that comes from appreciating the detritus our culture creates and abandons; they become in his paintings symbols of the hopes of the people who buy those objects. But with that appreciation, there is also a critique, an awareness of the lives mis-used creating worthless baubles and the violence their economy engenders. Perhaps this is where the toys and flowers meet: on the path towards a better world.

Ghada’s pictures of women come from porn magazines, not from the internet, which has become a highly-used source for many artists. I wonder if there is a particular aesthetic in the magazines. Does she choose them from certain cultures, or from a range of sources? They are all, she explains, from soft-core American magazines. Porn is disturbing, but the images becomes pleasant, even sexy, in Ghada’s work. Pictures created by men for the pleasure of men are reclaimed by a woman. She grew up in a conservative environment, where sexual expression was considered evil and closeted. Her religion and education told her such images were bad; now she wants to transform those images into something positive.

This desire to improve the world is evidenced in those collaborative works by Ghada and Reza that include verbal expression. Ghada has been using words in her work since the early 1990s; those texts concerned love and marital contracts. Later works dealt with ideas such as freedom, peace, security, and fear. In 2007, Ghada and Reza also made collaborative drawings that include text. One piece depicts cartoon characters from the Disney film Aladdin with the phrase “LOVE ENDS” repeating to form a circle around the lovers. In another, a smiling Snow White looks behind her to find the sewn phrase, “LOVE HURTS.” “WE ARE DESTROYING PLANET EARTH,” one drawing declares, while another states, “WE ARE TIRED OF WARS.” These straightforward sentences are a kind of hard realism that makes one think of religious concepts such as the acknowledgement that all existence includes suffering. In the current monoprints, there are a few word pieces with similar harshness. One has a border that repeats the phrase “NO JUSTICE NO PEACE,” and “LOVE ENDS” returns, starkly set this time in block letters against a paradoxically bright pink ground.

Woven and layered into these playful and decorative works are serious social and political critiques and philosophical skepticism. There is a sense in these new collaborative monoprints that Ghada and Reza have moved further into a metaphysical realm in their work. Nature is all around us in these pieces, as is politics. These are the larger pictures the artists are able to maintain at all times, while making decisions, trying out new techniques, or just entertaining each other.

The emphasis on natural and political contexts make me wonder if the plants are innocent? Are they naïve? Plants perform the essential acts of living. They have sex, they reproduce. They take over territories. Some are even carnivorous. They have suffered, as who has not? One senses that these artists have succeeded in finding the tenor of our times, yet how they have done that is baffling. It feels effortless, almost evanescent.

Ghada and Reza were like travelers, coming to a culture known yet unknown, where they would try many different tastes, swimming through different pools, putting on different textures of clothing. Only, it was not they who would do the swimming and trying on of garments; it would be their surrogates: their images.

|