home | books | poetry | plays | translations | online | criticism | video | collaboration | press | calendar | bio

| Art Books and Catalogues | Curatorial | Poetry | Translation |

|

|||

|

Francesco Clemente, Ten Portraits One Self Portrait, 2008, Gian Enzo Sperone, Sent, Italy |

|||

|

MY FRIENDS is somewhat of a joke, the water gracefully does he really know her? the concerti grossi which makes me wonder — who are my friends? it’s not easy to talk about this, that’s why Vincent Katz |

|||

|

EVENING BLOSSOMS ‘Tis better to sink than to fink Here lie the remains of last night’s battle, That glowing stone, the fire of Sappho Ancient harmony of those islands flows even unto “Why have you changed toward me? But that fire cannot be ignored which flames up Vincent Katz |

|||

|

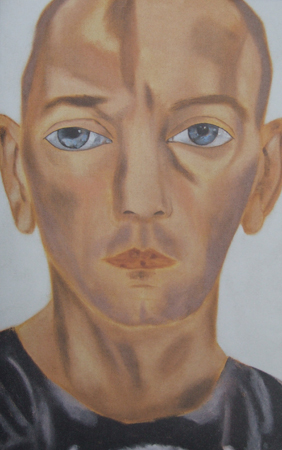

Francesco’s Friends These paintings are not depictions. A dimensional illusionism is quickly felt in the planes of faces, necks, and shadows, but noses often flatten into those planes. The background colors are generally uniform. Abstract patterns occur in facial shadows; garments provide regions for image-transformation. Correct anatomy applies from head to body and arms, but sometimes arms are too small for the head size. This kind of scale-rupture has been given the name Expressionism. What is being expressed in these new portraits? Rene Ricard. Poet, critic, friend. The hands, one grasping the other. The look in the eyes, accepting of life, but there is sadness there, beautiful green. The mouth twisting to one side, recognition of life’s savageries. The all-night theater. The endless waiting. The screams. All subsumed into an image of ultimate urbanity: poet as Baudelairean flâneur, man-about-town, someone able to put it all in perspective, as a painter should, but a writer does it differently, quicker or slower. He is well dressed; gridded shirt, earth colors, looped scarf or neck kerchief. He is suave, collar and lapels swaying out with bravado from the shoulders, the head at a certain tilt that says, “I know this,” and “Okay, it is not all so great,” and “I fit into the ultimate frame.” Father Pierre. A significant, erect, visage. This is a gentleman — or a man of the people — someone to be trusted. His head tells us that, or projects that, erect on the stalk of its neck, eyes peering intently into ours, a look of beneficence. It means not that you are happy, or that you know better than other people, but rather that you accept people and things as they are. Abstraction takes place in the white-collar segment, brownish columns of cloth supporting it (as the neck-column supports the head, one continuous upright). The painting contrives a way to mimetize the man. Tom Levine. The eyes are watering. Is this man crying? His head is turned slightly. His nose expands to the right. His hair is brushed elegantly out to the sides. His forehead is a great dome of human existence. He has delicate eyebrows. His lips carry centuries of European suffering, and refinement. Michael Stipe. Rock and roll, but also a person in the room, with an equal interest in what they all are interested in: art, poetry, fashion, music, theater. An esthete. A sensualist. His eyes, grey-blue, bright harbingers of his whole expression as a person. The look is self-confident, awake, but not domineering. How could one be, in this day and age? Donald Baechler. Painter, friend, colleague in decades of painting war in this City. Donald Baechler always wears shirts and jackets. Here, he has taken off his jacket, is still wearing his shirt. He is relaxed, so relaxed he may be dancing. His right hand touches his left side; his left hand rises to push against the picture frame, away from his left ear. The grey mottled background suggests a day of painting. There are many dips and gullies in this portrait: beneath the eyes, at the base of the neck, in the back of the hand, below the wrist, at the sides of the face. These are all beguiling, suggestive. The darks and lights of a personality one knows well. Self-Portrait (in Drag). The intense redness of it. As though it was all painted in red before the painter toned it down by slapping on a black mini-skirt, tight, feathery top and black bustier. The red burns through the dark-haired wig and the skirt. The face, too, is dark, framed by white beard and moustache. This is not a head and shoulders, but rather the whole body, from the thighs up. The curves are essential. All portraiture is drag, and all self-portraiture. Here, the artist who has done so many self-portraits re-invents himself. He is not the introspective time and space traveler of yore, but rather the party-goer of this day and age — the person of indeterminate predilections, about to go out you don’t know where. Nina Clemente. She has an authoritative look, almost a sneer in her eyebrow arch and lips. The hair is unusually painted. At first, you read it as hair, because it comes from her head and falls down to her shoulders. When you look more closely, however, you start to see it as shaped, snake-like, coils, painted brusquely with brown paint. These shapes, which can also look like calligraphy, or writhing figures, are what fall down onto Nina’s bare shoulders. She is more dressed up than the others, in a strapless gown, whose shapes also take on lives of their own, as shells or faces. Like Stipe’s, Nina’s arms seem small for her body. It is as though the painter wanted to see what she was capable of, what she could make, rather than making her a static figure. Either way, she is goddess-like. Tunga. The expression works at the viewer; the twist of the mouth echoes the tilt of the eyes. An authority accrues to people take who assume one name: Liza, Caetano, Bird. Tunga is in that category, a sculptor whose work is known around the world. Here, in addition to his twist, his personality is signaled by the cigarette in his right hand. The hand itself is dominant, resting on the bottom of the picture frame, its veins popping out like roots. It is a serious hand, a hand of action. Behind the hand, a white jacket: sign of purity, or a doctor’s careful precision. Within the jacket, a dark grey shirt appears, open at the neck, allowing the painter to create one of those diving neck shapes of which he is so fond. Miquel Barceló. Barceló is of Clemente’s ilk: a painter of large, expressive canvases, whose dark tonalities suggest an elemental quest. Here, he looks, his lips pressed together. The curl of his nostril is noticed. His hair, like Nina’s, is clearly painting, and not the hair it at first seems. It is grasslike, spiky and has an animal-like gesturality. Symbolically, the painter raises a sea shell in his left hand. This is the continuity of crustacean to mammal, and redolent too of hearing, complement to the artist’s vision. Barceló’s bright green shirt and fiery jacket are evidence of Clemente’s own preoccupations with how color can be made to speak. John Currin. This is an unexpected view of the celebrated painter. Where we might expect self-confidence to radiate, instead an uncertain, possibly sad visage looks out at us. Its tentativity is signaled by the slight turn and tilt of the head. Even the hands, joined at bottom right, are tentative, signaling dominance but also insecurity. They do have the thick veins of creativity on their backs, however. The blue-green shirt is opened at the neck to three buttons, allowing a large expanse of light flesh to appear in a down-pointing wedge. Scarlet Johansson. Her eyes are enormous, but instead of mesmerizing, they are almost globe-like, like looking into two huge fish tanks. They dominate utterly the mouth, which we remember so vividly from photographs. The hair, too, is pulled back severely, not allowed to cascade. Her arms fit her body, though the body may be slight for the head. How does Francesco make these works? There are no studies. The paint is thin, and edges are feathered. What is being expressed is an idea of a painting — the format, the size, the particular colors — and also an idea of how to show someone. The bottoms of the paintings are the places for meditation; the tops are for social confrontation. One could examine the evolution of Francesco’s colors, from the earlier, paler, tones, to later experimentations with more vulgar fields. His has always been a mischievous flirtation with past and present, with high and low culture, with formality and informality. In these affecting portraits, he reaches deeper and catches his subjects’ more human aspects. |

|||