|

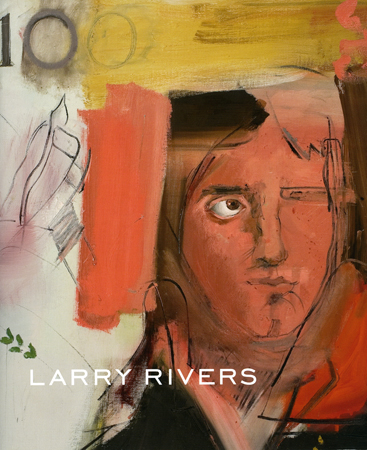

Larry Rivers : Eternal Renegade

by Vincent Katz

When looking back on Larry Rivers’ early work, one cannot escape the feeling of paradox that gives it life. The paintings and drawings he made in the early 1950s have a recessive style that belies the sense of danger implied by the artist’s impulsive personality. His attack on the then-moribund form of history painting, as exhibited most famously in Washington Crossing The Delaware (1953), is a case in point. Although Emanuel Leutze, who depicted the same subject a century earlier, is not a great artist, he comes from the classical tradition of painting and draughtsmanship that Rivers almost obsessively wanted to enter. It may seem odd to characterize an artist so insistent on tackling portraiture, still life, and landscape, in techniques that recall Ingres or Cezanne as a renegade, but a headlong quality was central to Rivers’ nature, and it was to emerge more forcefully as his work matured from the late 1950s through the mid-1960s.

Rivers’ artistic development, defined by a devotion to craft, flourished in collaborative spaces. The story of how Rivers, then a jazz saxophonist, met Jane Freilicher in 1945, and through her, Nell Blaine, is well known. Rivers imitated Blaine’s work and impressed her with his persistence. He drew almost constantly and spent a year studying under Hans Hofmann. By 1949, Rivers had met poets Kenneth Koch and John Ashbery and shortly thereafter Frank O’Hara, initiating a period of cross-fertilization of which O’Hara’s and Rivers’ lithographic collaboration, Stones (1957), is only the best-known example. O’Hara wrote admiringly that Rivers appeared on the Abstract Expressionist scene “like a demented telephone” — his diverse classicism could not at first be placed, though its communicative power was instantly recognized. Ashbery has clarified how Rivers in the early 1950s seemed a compendium of rapidly-evolving styles: Bonnard-esque; expressionist in the manner of Soutine; then something more delicate and simultaneously modern.

Throughout this evolution, drawing remained of prime importance. Fairfield Porter, in “Rivers Paints A Picture,” (Artnews, January, 1954), observed, “For Rivers, drawing is the most important part of painting, to which everything else is subservient and dependent.” Describing Rivers’ process, he noted, “When he draws, Rivers rubs out a great deal; about as much time is spent on erasing as on making marks.” While Rivers was lionized early on in his career — he was included in a 1950 show organized for Kootz Gallery by Clement Greenberg and Meyer Schapiro — it wasn’t until the mid-1950s, while living year-round in Southampton with his ex-wife’s mother and his two sons, that Rivers hit on his classic mode: heroic, large-scale tableaux, effected through a brushy technique. The approach owed not a little to Willem de Kooning’s muscular excursions but was modified by Rivers’ own determined use of what Raphael Rubinstein has recently termed, in another context altogether, provisionality. In Rivers’ case, this was attained by erasure, painting out, and the use of multiple views of the same figure or limb.

The current exhibition provides an occasion to examine this fruitful period in some depth. There are monumental early portraits, such as Augusta (1954), a nude portrait of his first wife, and O’Hara (1954), a scandalous nude portrait of Rivers’ collaborator and lover; paintings that gather subject matter into planes of painted incident, whether interior as in The Wall (1957) or exterior as in Southampton Backyard (1956); paintings based on photographs, such as Bar Mitzvah Photograph Painting and The Last Civil War Veteran (both 1961); paintings based on commercial design, such as French Money I (1961) and Three Camels (1962); and at least one vocabulary lesson painting, Vocabulary Lesson (Polish) (1964-65). Of great interest is the selection of drawings, including 1950s portraits of O’Hara and Jack Kerouac and a study for Stones. These allow us to analyze Rivers’ compositional approach and his precise use of line.

Rivers was in some ways blown out of the water by Andy Warhol’s arrival in the early 1960s; the effect of Warhol’s photo-based works derailed a great many artists, including, it could be argued, Rauschenberg, and his influence continues to be felt today. If we deem that influence detrimental, it is not to denigrate Warhol’s achievement but on the contrary to underline how pervasively it submits other artists to its identification. As this exhibition demonstrates, Rivers started long before, in a very different place — a place of innocence and the conquest of technique and public imagination.

In the 1970s and later, Rivers’ renegade character became somewhat ossified, unalleviated by a concomitant struggle for technical discovery. In stressing this quality of character, or personality — which remained throughout Rivers’ life a source of great personal charm — one remembers the signal role technique played in his early devotion to the craft of drawing and painting.

|