|

Sarah McCoubrey : Looking For The Normal

by Vincent Katz

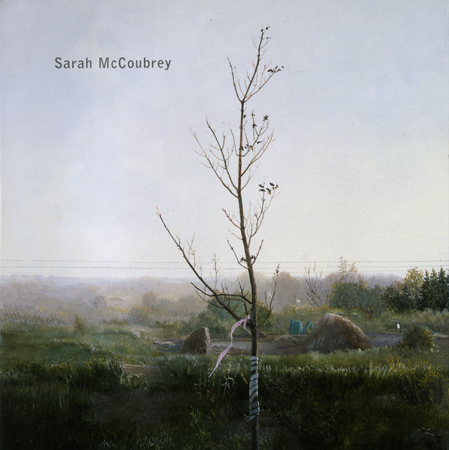

Sarah McCoubrey loves the moment of coming upon something. It is the moment her paintings obsessively, repeatedly, recreate. It is that moment Corot too loved: of seeing the light when just having emerged from a woods towards an open field, or leading to a pond’s edge. McCoubrey finds very similar moments; her achievement is to find them in normal American settings. She does not go out of her way, and she does not fantasize a false idyllic wilderness. Instead, hers is the average countryside of rusted tanks and fading signs, telephone wires and tagged trees.

What attracts one is her adeptness. Branches are her ultimate metaphor, the line as branch, but she is equally proficient at grasses, buildings, wires, reflections, clouds. Her paintings are fruitful sources of observation, for the painter and for the viewer. Although her pictures are clear, McCoubrey’s paint does not describe but has a life of its own. She has found a way to have her paint remain in delicate motion. Her main subject is light itself, and this she is able to evince most effectively: the overall glow of an afternoon, whether it be in winter or summer.

McCoubrey’s compositions are thoughtful and precise. Hers is a careful drafting: not only of lines but ideas; America as a haunted place. The evidence of people is everywhere — the sense of them — but they are not visible. The scale of the works is demure, but it combines effectively with her technique. She is not trying to make the next big thing, turn realism into camp. Neither is she content with a staid realism of the past. Like her subjects, her painting requires a new vision. It is a vision tempered by the work of a painter like Rackstraw Downes, who has looked deeply at disregarded American sites, translating them with brilliant technique into reduced, patently artificial images. McCoubrey’s subjects are different, and so are her compositions. Where Downes likes edges of industrial sites or abandoned urban thoroughfares, McCoubrey seeks out rural edges and focuses on unnoticed objects, making them of central importance. Her compositions are more classical than are Downes’; his are more modern. But McCoubrey’s pictures have a subtle, powerful identity. The particular sizes and formats give them this personal air.

Her pictures of anonymous places, done mostly in upstate New York, are neither celebration nor critique. The paintings depict what is there: a sense of atmosphere, settings for landscapes whose figures are trees, buildings, signs, and junk. When she shows a cut tree and stumps in the foreground of a painting of scrubby landscape, it is not felt as a commentary on man’s depredation of nature. That man has usually built without ecological consideration is taken for granted in these pictures.

Skies play a significant role in McCoubrey’s work, occupying at least half, often a little more, of the picture spaces. Her skies are unblemished: areas of cloud and color untouched by men. One also feels here reference to, and reverence for, other skies of other painters: Tiepolo and the Dutch landscape painters. A storybook nature of distant buildings often anchors her compositions. What McCoubrey is best at is painting the overall light surrounding overlapping branches devoid of leaves. This is a signal accomplishment that makes her work worthy of the attention of anyone interested in contemporary painting.

An example of McCoubrey’s compositional skill can be seen in Building Lot (2008). There is here a subtle exegesis: the foundation of the building stands for Spring, which is in the air. The balance between the cloud-invested sky and the growing, human-influenced, earth below is one of equilibrium. The bright red banners in the foreground form a decorative motif, and also a barrier between the viewer and the scene. The geometric pattern effected by quadralinear cinder blocks encloses piles of raw earth, while at the front of the picture, nature’s relentless grass threatens to overcome the structure if left too long dormant.

McCoubrey’s graphite and charcoal drawings on gessoed paper are well executed. The images have a starkly defined quality and sit in expanses of unmodulated paper. It is clear that she takes pleasure in the act of drawing, of scratching the image onto her prepared grounds. Apparent, too, is the care with which she prepares her compositionally and tonally more complex paintings.

McCoubrey has set up expectations in the viewer: that she is serious about the technique of oil painting, that she is aware of and invites comparisons to master technicians of the past. Her images feel comfortably full-fledged. One almost hopes she will continue painting in this vein — in similar size and subject — working on better seeing and translating her particular American vision. On the other hand, one would be curious to see what would happen should she decide to do something drastically different.

There has been a debate for centuries over whether man’s incursions should be considered natural. McCoubrey’s answer seems to be that, while humanity’s effects on the planet can have devastating consequences, they are not only subsumed by also to an important extent ignored by nature. More importantly, her work is a stimulus to seeing. Her paintings make us aware and appreciative of scenes we may pass every day without paying any attention. They also cause us to question what we see as normal, or natural. Whether we can shift the norm is up to each of us.

|