home | books | poetry | plays | translations | online | criticism | video | collaboration | press | calendar | bio

| Art Books and Catalogues | Curatorial | Poetry | Translation |

|

|||

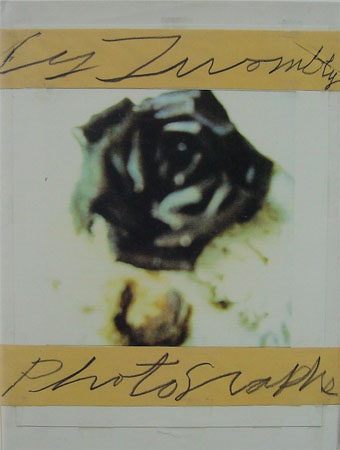

| Cy Twombly Photographs, 2002, Schirmer Mosel | |||

|

Cy Twombly Photographs Even though by now the dissociation between experience and photograph is well-known, still, because it uses a mechanical means of image-making, the idea that a photograph registers a moment, verifies for all time an actuality, retains a strong hold. Artists have always known that photography is a medium, and they have manipulated it with greater or lesser technical sophistication. What is so appealing about photography is that one u can achieve effects with a minimum of technique. To accumulate a body of work, though, requires patterns of working. Even if they start haphazardly, activities settle into methods the artist chooses to achieve desired results. Against the monumentality of the photograph-as-artwork and the nonchalance of photography-as-reality, some artists today have chosen to pick up a thread in the history of photography-as-something-like-painting. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Pictorialists emulated painterly effects in their photography by use of soft focus, matte paper, and handwork on negatives with color and brush.è These artists were fleeing photography’s stigma of literalism, which Baudelaire had mocked. At the same time, they introduced symbolist narrative elements into their work. Murky shadows and indefinite borders suggested a world well beyond that of the everyday, a world of fantasy and mysticism, of belief as opposed to the hard knowledge of earning one’s daily bread. Cy Twombly takes the Pictorialist tradition into another realm or realms. He takes it into abstraction, and he takes it into antiquity. Both these areas can be seen as extensions of the Pictorialists’ interests, but both represent striking achievements. After the Pictorialists, few have touched again those long-lost fin de siècle chords. Photographers have opted for crispness, Cubism, Surrealism. They have experimented with the photogram and photomontage. Atget did photograph the mystery of Ôthings, but the definition of his images is far from painterly concerns. The autochrome process, first made commercially available in 1907, yielded a dimming of tones and registered light with a diffuse, grainy quality. Likewise, a predilection for photogravure, the printing of a photograph from an etching plate onto matte paper, yielded a softening of detail, a melting in of the image into the paper’s texture. Twombly, too, prints his photographs onto matte paper, but instead of the high artistry of photogravure, he opts for a version of the standard color photocopier [more?]. From the commonest means, like the monk’s habit, comes vision. Edward Steichen’s The Pond -- Moonlight (1904), with its reflections of loosely defined trees and pinkish light source disappearing behind the horizon, not to mention its exquisitely planned composition, brings to mind the paintings of Edvard Munch more than anything in prior photography. Twombly’s photographs also confound one in a spatial sense, a Ónd they are deathless as well as depthless, in that they do not derive from ordinary life. Many of Twombly’s photographic images represent a personalized awareness of art that makes direct use of other art. There is a shutting-off -- of emotion, of breath -- when one realizes that Twombly’s hazy photographs of trees are in fact photographs of sections of a painting in his home in Gaeta. That realization becomes the key to seeing many of his recent photographs. These photographs, then, are not -- even when they are of three-dimensional, as opposed to two-dimensional, objects -- documentary in any way. Nor are they pure creation. Rather, they represent an obsession of focus that is disturbingly familiar. As photographs of works of art in the photographer’s personal collection, they show the expert, caressing eye looking, over and over, at the beloved object. In the final choice of images for the present portfolio, there are often three or four similar images of the same object. The d {ifferences are variations of mood, not of description. They are different breaths about the object. Not to explain it. To breathe it. Once this seeing is felt, it extends to the photographs of flowers as well. Though flowers are not works of art and will not last in their owner’s possession, still, on the day they were photographed, they were as much a part of the environment, needed by the artist to be cultivated, brought into a focus that is not the sharp focus of documentation, but rather the sliding focus of a glance. It is as though, through casual observation, one were allowed to become infinitely demanding. The deification of the casual, of course, is a hallmark of Twombly’s work, and something he shares with his longtime friend, Robert Rauschenberg. The photographs Twombly took in Rauschenberg’s studio on Fulton Street in Manhattan in 1955 reveal the random, agai un in a embracing way, taking it well beyond what could be considered de rigeur for chic bohemia and elevating it into something like a religious path. Another friend from the early days, John Cage, pictured in his A-Model Ford, did bring art and religion into consonance, and the glimpses of the early lives of these artists, and the spaces they inhabited, prove their monklike discipline and devotion. The photographs of Twombly’s early paintings in Rauschenberg’s studio are in another world altogether. Now it is not the detritus of the actual, but the ethereal glamor of ambitious art. These paintings have a pacing that places them next to any other paintings in any museum. The way the artist has stacked them, to photograph them, is part of the love he has lavished on them. They are his family, and yet they are beyond him too, partaking of the steam and streetlights of A series of details (clouds and sky) of a Mannerist painting is printed on a lightweight white paper. Then there are the flowers, in one case cloth peonies that, through the hold of the camera become bodied and sensuous. as well as fiery and overflowing. Many times (as in the statuary) this work is about how proximity changes one’s view, just as when one is up close to someone, one’s vision changes. An amazing golden maritime series, as of b ¢oats just arriving at sunset after a long day on the water, is taken from a painting of fishing boats in Gaeta by an unknown artist at the turn of the twentieth century: Twombly’s photograph has returned this painting to an aesthetic of its time. There is a photo of a Twombly sculpture (Pasargade, 1994) -- again the artist looking at himself, but this time the air is contemplative not turbulent, stark shadows forming a grid over the image and deftly coloring the sculpture’s base. Another sculpture (The Mathematical Dream of Ashurbanipal, 1999) also has a stark pattern of light and shadow draped over it. Window shades in Lexington take the place of sculpture to provide a warm, nurturing environment. Portraits of friends: Nicola del Roscio, Twombly’s editor, appears in a turban like a hip Pisanello in 1968. Rauschenberg in in New York with antique coat rack and black sweater. The artist’s son, Alessandro, now gr ⁄own up an artist too, poses next to a monumental bust of Nero. Twombly photographed Cage at Black Mountain College in western North Carolina, where he spent the summer of 1951 in order to study with Robert Motherwell. He also photographed another friend, Franz Kline, whose open smile looks into the box of the automobile, while the window’s edge seems to cut his eyes. In that moment, their impulses were in synch. Twombly was at the center. He reached and there, for a moment, the arts were in one constant movement. Then he had to paint. Vincent Katz |

|||