Multiple Simplicity: the Art of Yvonne Jacquette

by Vincent Katz

It was a curious choice, and a defining one, that Yvonne Jacquette made almost thirty years ago, to go up and look down. A view from above shared with her earlier work a limited viewpoint which could spawn a new way of seeing, but it was different. While based on common experience, it was not everyday experience. Jacquette’s aerial views artificially freeze transient moments, usually associated with ascent or descent. From the mid-1970s until today, she has painted only aerial views of urban and rural landscapes, at first from airplanes, then with increasing frequency from tall buildings. Her choice of path was not unlike those of her New York School predecessors, many of whom settled on defining formats, techniques, and imagery. Jacquette follows in their tradition by eschewing any thought of interiors, still lifes, or portraits -- even the term “landscape” has to be updated to include Jacquette’s visions. Yet Jacquette has always been firmly rooted in realism, and she takes a doggedly observant approach to her aerial subjects. It is the exacting attention to observable reality combined with a willfully exclusive choice of subject and viewpoint that give her work its singular resonance.

Jacquette’s paintings have been building in complexity over the last decade. She makes mid-size paintings that feel much larger than their actual dimensions. Judicious cropping and elaborate composition push the paintings’ energy -- the collective energy of many personalities -- far beyond the confines of the picture frame. Volume is a factor, but it vies for attention with two-dimensional invention. While buildings do project up into a third dimension from her surfaces, the distance between observer and subject often makes even these projections feel quite remote.

Jacquette is fixated on the romance of distance, a romance which is distinctly American, but her relation to the ground is never so far as to lose contact with individual scale. She is intrigued by the sight of a lighted window at night or dusk, as it is an indication of human endeavor that allows the possibility of contact. Her attitude is revealed by her interest in humanity’s physical creations, even while slyly pointing up their absurdity. She takes people as they are, with all their shortcomings intact, yet contact never goes beyond the realm of possibility in her paintings. We rarely see a figure, and when we do it is far away, too far to make out a facial expression or even a body type.

Everything is possibility or, one might say, shimmer. Jacquette has inverted the concerns of the Impressionists. She is involved with the shimmer not of daylight but of shadow. Still, this inversion makes her quite close to them, and, despite the separated mark-making emblematic of her work, it is not the Pointillists she most resembles, but Monet or Sisley, who painted grand urban vistas, seen from afar, as if taking a step back to say to an impressed companion, “There, that’s modernity for you!” That stance represents an embrace of change, distinct from those landscapists who search out pristine bucolic settings. Buildings, streets, automobiles, docks, boats, skylights, watertowers, skyscrapers, farms, airplanes, even a cement factory can take on an aspect of endearment in Jacquette’s paintings, since they exist and are simply part of the scene.

How about that angle, though? The view from an airplane is an archetypal contemporary experience, full of anticipation and uncertainty. Travel, particularly plane travel --which provides the possibility of rapid, drastic change in one’s locale -- can engender excitement and apprehension equally. Unlike the Impressionists, Jacquette’s airplane views are through a tiny porthole, so they can be shared only with difficulty and convey a sense of solitude.

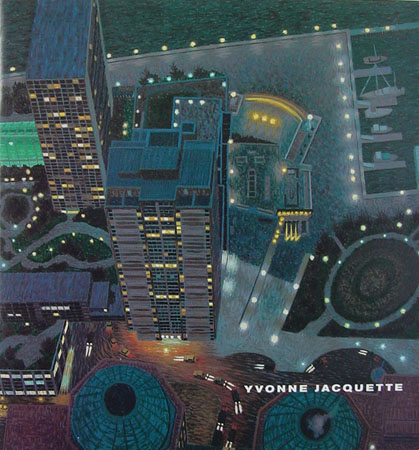

For the current exhibition, she has dispensed with airplanes altogether, focusing on vantages from high city buildings. Like the view from a plane, the view from a high structure is common to contemporary experience, but both are perspectives that have been little exploited by contemporary artists. In both cases, Jacquette has moved from more or less faithful translations to an increasingly artificial approach, in which she splices together segments from different locations and angles. Her combinations are so smooth they can escape our notice, and even when observed they are so harmonious as to become a new vista, which has an odd metaphysical effect, as though Jacquette has seen and depicted a reality distinct from the one we take for granted.

Here we have ten sights from lofty edifices -- six from New York, four from Chicago. These new paintings, all night scenes, explore deep reverberations of space. They are highly constructed subjects, based on first-hand experience edited and recombined by the artist, effectively unified by the romantic tone of artificial lights in dusk and nighttime settings. Often, we feel as though we are floating over great expanses, as in Hudson River and Two Angles of New Jersey or East River With Red Reflection. It is telling that Jacquette has replaced the airplane wing, which symbolized the artist’s diligence and modernity in earlier work, with the dragonfly (see Chicago River Fork II). Lured by nature’s scents, we are invited to float, independent like this durable insect, over vast stretches of water and city.

There is a theory of dreaming which believes that dreams of flying are of the highest value and that, to the extent that dreaming can be controlled, one should attempt to fly in dreams. This is the perfect analogue for what Jacquette achieves in these night paintings, which develop from imagery in Night Fantasies , Jacquette’s 1991 film collaboration with her late husband, Rudy Burckhardt. Jacquette explains that looking through the camera’s viewfinder at night, she was able to see only bright lights, while the rest became black. This encouraged her to work more freely with space in her paintings, often by eliminating or simplifying backgrounds. Some of Jacquette’s perspectives reflect those favored by Burckhardt, who used to scale high buildings in the 1940s to take photographs of rooftops or the streets below. In neither artist is the act of looking down an excuse for pronouncements from on high, nor do they share the ecstatic expansiveness of the Luminists, engendered by an exotic wilderness, for both Burckhardt and Jacquette prefer to honor commonplace subjects seen anew.

Jacquette’s fascination with the city has reached truly dizzying extents. She experiments compositionally, while tied to her vigilant accounts of architecture and urban design, all of which has the potential of unleashing a deeper emotional force, fostered by the interplay of tones and lighting. If she levies judgments on her subjects, she keeps them hidden. At best, we can say she presents her scenes in a favorable light. Even a work like Mixed Perspectives, From the World Trade Center, which would seem to depict the most mundane subjects (including the huge roof which dominates the lower left quarter of the painting), has nothing harsh to say about them. We are given the impression that Jacquette is captivated by the forms and textures she comes across, gazing down on typical scenes rarely analyzed, and relishes the opportunity precisely to subject them to analysis.

There are also associations each viewer may bring to a locale. With all of the World Trade Center pieces, specific places have been so clearly evinced that one may remember walks among these edifices, may picture himself down there among the shadowy figures painted or alluded to. With Vertiginous World Financial Area, Jacquette brings us close to a familiar Tribeca promenade and spot at which Scott Burton had inscribed on iron railings lines from the poetry of Walt Whitman and Frank O’Hara celebrating Manhattan. Like those two poets, Jacquette delights in her city, and she carries her passion over to the Second City as well. In two paintings, she shows a close up and a long shot of Chicago’s Gold Coast, famous not only for its luxury highrises -- which rival Miami or Rio de Janeiro for urban waterfront glamour -- but also for the Oak Street Beach, which as much as Central Park does for New Yorkers, provides a democratic gathering point for Chicagoans. In North View of Downtown Chicago, Jacquette alludes to the famous gridded beauty the city projects to the arriving or departing plane passenger; in a witty conceit, the top edge of the canvas could double for Lake Michigan’s horizon line, though it does not.

These paintings revel in variation, from the diagonal division of Oak Street Beach and Lake Shore Drive to the ever-unfolding Y-shaped progression of Chicago River Fork II, whose perspective is cleverly enhanced by the aforementioned dragonfly. The most intoxicating painting of Chicago may be Lake Shore Drive, partially because of its perceptive choice of subject, partially because of its compositional split between city and nature, but mainly for the poetry manifested in the time of day, the sensation of in-between time, night about to fall, cars heading home from work or out to dinner, but enough light is left to produce the shocking tones of blue on building tops and lake, reflecting sky’s last vestiges of day. In a work such as this, we see how, building from formal inventiveness and persistent attention to detail, something much greater can develop -- a desire and respect for the mystery of life.