|

Stewart MacFarlane, Painter

by Vincent Katz

Stewart MacFarlane is in mid-career -- like the news that Joey Ramone recently died, or that the Buzzcocks have reunited, this news makes us feel old. Old, but happy, as we have been able to witness the development of a remarkable artist, and one who himself still seems to be in the first blush of youth. There is an undeniable energy to MacFarlane’s paintings, an excitement in his seeing, planning, constructing, and ultimately unveiling a shocker that transmits itself to the audience.

The word “audience” is not literally accurate when referring to the visual arts, as it properly applies to hearing an artist and only by extension to seeing or reading. In MacFarlane’s case, however, I feel no chagrin using it, as the performative, exhibitionist, element of his work, redolent of his time as a rock’n’roller, is central to its experience.

MacFarlane grew up in Adelaide, where he studied art in secondary school with David Dridan, who opened MacFarlane’s vision to the possibilities of being an artist. As MacFarlane has written, “I could see his paintings hanging in real galleries.” The student began frequenting such galleries, where he first came into contact with the work of Arthur Boyd, Robert Dickerson, Sidney Nolan, and others. Again MacFarlane: “This experience made a lasting impression on me. I liked the ‘good life’ feeling of the cool, shady galleries... The paintings on the walls seemed huge and extremely impressive. Someone had concocted these images from their imagination, on their own terms. They existed in this time...”

From St. Peter’s College, MacFarlane entered the South Australian School of Art at age 16. There he learned principally from David Dallwitz, who taught MacFarlane the art of building a composition through weights of tonality, the classical technique of chiaroscuro transposed into contemporary subjects and colors. Dallwitz encouraged MacFarlane in his dream of moving to New York, putting him in contact with the sculptor Clement Meadmore, whom MacFarlane met only once, before signing up to study at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan in 1975.

The mid-seventies were an exciting time in New York on a number of fronts. As well as being an artistic capital since the heyday of the Abstract Expressionists, and providing access to major works by those artists in the city’s museums, New York had also been the site of many subsequent art movements of international importance, including Pop, Perceptual Realism, and Performance Art. By the mid-seventies, though, the dry rigor of the reigning modes of Minimalism and Conceptualism had left the environment a little enervated. In an oddly parallel development, popular music, which had seen such a creative and experimental efflorescence in the 1960s (to the point of the coincidence in 1968 of Jimi Hendrix’ distorted version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” with Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “performance” of recordings of various national hymns)1 , had reached a similar point of over-inflated bombast and self-importance. What was wanted, in both visual art and pop music, was a release of vital energy that could cut the Gordian knot of over-intellectualizing and bring back the quickness of immediate adventure.

In pop music, bands like the Ramones, Television, Richard Hell and the Voidoids, and Patti Smith were creating a scene at Max’s Kansas City and CBGBs that would initiate a sea-change in popular culture. What they promoted was a fast, loud, streetwise approach that not only did not rely on technical skill but often reveled in the very lack of it, or at least the inhibition to undertake a piece without worrying whether or not one’s skill were up to the task. Of course, there was a conceptual element to this approach, just as much as with Minimal art, but different in being based on a looser, physical approach to art. In that, it can be said to have more in common with the physicality of Jackson Pollock’s or Willem de Kooning’s attitudes to painting, mixed with some of the wry cynicism of a Claes Oldenburg or Jim Dine.

In painting, a similar phenomenon was taking place, a “dumbing down” of art in the sense of using blunt, semantically quasi-opaque images while simultaneously returning to the “primitive” and officially outmoded technique of paint on canvas. Artists like Dan Friedman (whose magazine D.U.M.B.O , a purposefully selected acronym for Down Under Manhattan Bridge, epitomized the raw attitude of the times), Richard Bosman, Elizabeth Murray, and Jonathan Borofsky were painting in a roughly expressionistic style, incorporating identifiable images in their pieces. While Murray was more interested in objects of daily use, such as coffee cups and shoes, rather than the human form, all these artists seemed to be searching for archetypal images -- people engaged in raw primal struggles, braving the elements or suffering disasters. These confrontations had a matter-of-fact quality to them, though, unlike similar ideas that had motivated the Abstract Expressionists.

This was the New York that MacFarlane knew during the years 1975-1982. In fact, MacFarlane straddled both the pop music and art worlds. He led a band during those years, Stew Lane and the Untouchables, whose single “Play This Song/Perpetrator” I remember well. I also remember Stewart. He worked for a time as an assistant to my father, the painter Alex Katz. I remember discussing the Kinks’ song “Australia” with Stewart, among other things. Through the School of Visual Arts and the painter John Button, who taught there, MacFarlane was introduced to a special part of New York’s art world, in fact the one he most credits with his artistic development at the time, that of New York’s Realist painters.

Since the early 1950s, there had been a strain of objective painting in New York that had its successes (usually not as notorious as those of the movements mentioned earlier and therefore only tardily acknowledged in official histories of the times). Jane Freilicher, Katz, Fairfield Porter, Larry Rivers in the 1950s and John Button, Rackstraw Downes, Janet Fish, Al Leslie, Willard Midgette, Philip Pearlstein, Paul Resika in the 1960s were among the artists who represent this vital counter-current in the art of the times. All continued actively in the 1970s and beyond and were successively better recognized for their contributions.

This is a disparate group of artists, ranging from Rivers’ almost Pop image-reliance to Resika’s practically abstract planes that double as boats and bodies of water. Within that range, there is, with particular relevance to MacFarlane, a renewed interest in how to make a contemporary depiction of a person. This can be a portrait of a recognizable person, as in Katz and Porter, or an attempt to create a contemporary version of that timeless image, the nude figure, such as Pearlstein has made.

At the School of Visual Arts, Button became a mentor, encouraging MacFarlane and advancing his conception of structuring a painting through tonal harmonies. To support himself, MacFarlane worked as studio assistant to Button, Fish, Katz, and Midgette. Today, this time-honored tradition of working in an artist’s studio may be in danger of going by the wayside, as art schools stress theory and techniques of making professional contacts over those of creating sophisticated art. As an apprentice, one gains the unsubstitutable experience of assisting the artist and simultaneously learning by watching how he prepares the grounds of his canvases, how he mixes colors, the kind of preparatory studies he makes, how he transfers the formal and textural elements of those studies to a larger canvas, and the process -- different in time and approach for each artist -- by which he ultimately gets the paint on the canvas in the desired manner.

In examining MacFarlane’s own output, we may make the following observations in regard to color, technique, and composition. Certain early paintings, such as The Office, 1974, make use of a Pop-influenced frontality. Already in this painting, the elements of violence and sex are present, but in the future the danger will become less obvious. Some paintings show the influence of Katz in abrupt compositions with large close-up heads and bodies cropped unexpectedly by the edge of the canvas. MacFarlane’s actual technique of painting -- and it is notable that he paints almost exclusively in oils -- seems to relate most to that of Janet Fish. In Fish’s elaborately artificial still lifes, her art of mark-making and her jazzy approach to color become the real subject. MacFarlane’s technique is always interesting, toeing the line between precision and fluidity. His sense of composition, which may be his most defining quality, owes something to the compression of Pearlstein and perhaps something to a painter like John Moore, whose landscapes present odd confrontations of foreground and background.

It is possible to see in MacFarlane’s paintings the solid grounding in depicting the observed world that he gained in New York combined with a sense of fantasy that, at least so it seems to this American author, could only have arisen in Australia. An artist limits himself by unawareness of international trends and likewise by slavish imitation of them. Each artist must grow from his native soil (native in a specific sense of this neighborhood, this road), but he benefits by knowing what’s going on around the world. We can imagine MacFarlane taking inspiration from an artist like Arthur Boyd, in particular, and to a lesser extent, Sidney Nolan, to arrive at an exciting fusion of paint-intelligence with a free-ranging invention. Boyd’s Woman Injecting A Rabbit, 1973, gives an idea of the area, with a bushy-haired nude woman rushing in from the left to secure and inject a black rabbit sitting on a table before a window looking out on a brightly-lit landscape. The image attracts our interest, but the paint holds it. There is also MacFarlane’s brash use of color, an expressionist, almost Fauvist, system of substitution quite different from the more homogeneous use of color favored by the younger New York artists of the 1970s.

All I have spoken of so far is background, the essential groundwork that enables an artist to do what he can do. What MacFarlane himself does is all his own. It comes partly from the movies, the film-noir tradition and its more lurid descendants, both filmic and literary. Partly, too, it comes from rock’n’roll. The frontality of the sex in MacFarlane’s paintings and the luscious impossibility of the women have to be seen in terms of the scene. So should the sexual ambiguity in certain paintings. Not only an openly androgynous piece like the drawing Jackie, 1989, but in every image of the male genitalia we’re back to that queer edge that even the straightest rock’n’rollers must necessarily confront. This sexual world is not meant so much as an affront to straight society as a matter-of-fact account of a life. This is not to say that MacFarlane’s images are documentary, although the male protagonists usually bear a strong resemblance to the artist. Rather, his images, even those with a slightly surreal edge, come from a real world, heated up by the artist’s invention.

How the audience responds -- whether they cheer or boo -- depends in part on their moral make-up. In recent years, explicit sexual images of all stripes have become commonplace. What distinguishes MacFarlane’s images partly is their brightly painted palpability; they are much more sensuous than the photographs usually used to capture such material. Also, queer flirtations aside, it is by and large a straight white male world. This may raise some hackles and is probably calculated by the artist to do so. Balthus is the classic case of an artist probing taboos, but his images are back in the male-gaze world, albeit given unique psychological juice. MacFarlane’s brand of prurience has more to do with artists like Eric Fischl and David Salle, straight white males who have continually pushed buttons with their tawdry views of the female sex. Unlike Salle’s media-oriented images or Fischl’s psycho-social portraits, MacFarlane’s deal more intensely with the interaction, or lack of it, between people. In a funny way, his lack of commentary comes back to Katz, whose group portraits have been noted for their avoidance of narrative. We can weave intricate tales about MacFarlane’s people, but someone else can easily weave quite different tales. MacFarlane gives no easy answers. When one first sees his blond bombshells and men at the ready, one expects a two-star hard porn flick, but MacFarlane deftly subverts that expectation.

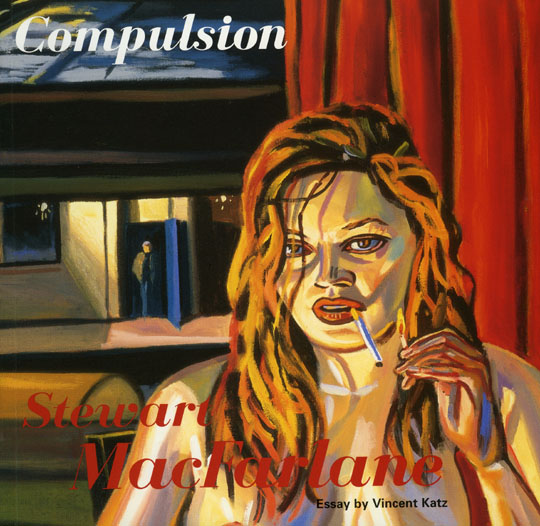

His are not classical female nudes, modestly accepting the male artist’s authoritative gaze. In fact, there is a range of relationships for the men and women in these paintings. In The Bike Rider, 1985, and Compulsion, 1986, we have man alone (to the point of being completely naked) with vehicle. In both cases, the men are at the mercy of somewhat sinister forces around them. Manhattan Memory, 1986, which clearly does not take place in Manhattan, is a painting that partakes of a nightmarish quality reminiscent of David Lynch’s best work. Particularly unsettling is the mirror on the back wall which should reflect the observer. A sense of dislocation accentuated by the cropped figures informs View Street and The Seventh Floor, both 1987. Full frontality of the women in Secrecy, 1988, and The Late Show, 1989, indicates, in these cases, woman who are in control of their own sexuality. Even in Young Artist and Model, 1988, and Outcast, 1996, in which women lie or float on their backs, the direct eye contact they make with the viewer makes the viewer conscious of their humanity.

From 1989, as indicated in the painting Restless, MacFarlane achieves ever greater fluidity of composition. His images seem to jump off the canvas with little of the roughness that sometimes stops the eye in earlier work. Although there is still a refreshing ambiguity to his paintings, there may be a greater sense of empathy, especially in the depictions men. My favorite paintings are the latest ones, in which a normal situation (watching tv naked in bed) can be given a paradisiacal, if unnatural glow. Conversely, an “unreal” image, such as Tower, 1999, attains an earthy presence by the harmony of colors and forms and the integration of man into his environment. MacFarlane is clearly at the top of his game and set to rise.

|