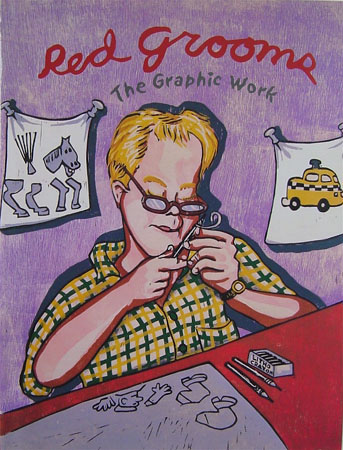

The Prints of Red Grooms

by Vincent Katz

I. Beginnings

Red Grooms’ first print, the linoleum cut Minstrel (1956), already suggests the exuberant theatricality that would come to define his mature work. Although he made it while enrolled in Peabody College in Nashville, pursuing a degree in teaching, it represents more than an academic exercise. Grooms had gained experience during brief stints at the School of The Art Institute of Chicago and the New School for Social Research in New York, and he put it to good use in this punchy, clear image exhibiting an energetic line and Grooms’s native subject matter. “Both in Chicago and New York,” he explains, “I had done a lot of drawings, pencil and ink. I didn’t do any paintings at all. I didn’t even do watercolors. I just did black-and-white drawings. I was developing some peculiar imagery.”(1)

Informing the Minstrel image is Grooms’ love of the theater and movies, both of which were to play seminal roles in the conception and the actual production of his mature art. The minstrel in this print is wearing a top hat, an important early symbol for Grooms of a crazed stage persona, a mad professor gone vaudevillian. One of the first artists to make an impact on him while he was still a teenager, had been Jacob Lawrence, and in Minstrel, Grooms attempted to combine the enthusiasm of his personal stage experiences with the formal and social sophistication he had observed in Lawrence’s depictions of African-Americans. Access to reproductions of art was important to Grooms’ development, and received images were soon to make themselves evident as subject matter in his work.

In the summer of 1957 Grooms went to Provincetown, where he studied for two weeks with Hans Hoffman and met Yvonne Andersen and Dominic Falcone. Their Sun Gallery was showing post-Abstract art that would prove to be a catalyst Grooms needed to arrive at his own vision. From his reading and observation, Grooms was attracted to the improvisatory bravura of the Abstract Expressionists, but he was also drawn irresistibly towards the human figure and various characters he wished to depict. After the summer, Grooms moved to New York with Andersen and Falcone, and in 1958 they produced a portfolio called City, designed by Andersen with prints by Grooms and Lester Johnson and poems by Falcone. Grooms’ four prints--drawings that Andersen reproduced on a small letterpress--are in black-and-white and reveal the facility he had by then developed in line drawing, as well as an interest in the macabre in one of the images, The Operation. At this stage, though, Grooms’ treatment of a body being operated on still relies on the fantasy appeal of the movies. In particular, it brings to mind Frankenstein, the monster Grooms would later play in Rudy Burckhardt’s film Lurk (1964). Also in 1958, Grooms made Five Futurists, a linocut based on a famous photograph, which is the first example in Grooms’ work of art-historical figures as subject matter.

In 1959, back in Provincetown, Andersen and Falcone’s Sun Gallery was thriving with shows by Johnson, Alex Katz, and Anthony Vevers. Allan Kaprow came up at the end of the summer, and there was much discussion about a new kind of art that, taking its cue from Jackson Pollock’s “Action Painting” (as critic Harold Rosenberg had called it), would make action itself the art. That September, up in Provincetown, Grooms staged his first Happening, Walking Man.

Back in New York, Kaprow and others began doing Happenings--brief events with elaborate sets performed in front of an audience--and they began to attract attention. Grooms had an alternative space then, which he called the Delancey Street Museum, and it was there in December of 1959 that he staged The Burning Building, perhaps his most famous Happening, and one upon whose imagery he would draw in the future. Grooms’s Happenings were never as free-form as those by many other figures; they were more like mini-plays. He made a woodcut to advertise The Burning Building, posting copies downtown. Although it was his first woodcut, it shows a maturity not evident in his previous graphic work. The interaction of the strongly outlined figures with each other and the urban backdrop behind them is deftly effected. The elegant lettering has the perfect blend of clarity and irregularity needed to render it intensely alive. Lettering would continue to be an important part of Grooms’s graphic output, as would the intensive use of poster advertising.

During this same period, Grooms put out a mimeographed Comic (1959), at the request of Claes Oldenburg, who was having his Ray Gun Show at the Judson Church. Grooms’s comic book, printed in black on pink paper, folded and stapled to mimic the appearance of a real comic book, revisited the big-city danger theme of firemen that so intrigued him. Comic provides tangible evidence of a key element in Grooms’s repertoire that would distinguish him throughout his career: the humor and silly outrageousness inherent in comics or funny papers. With their serial frames, bright, eye-grabbing colors, improbable plots, and light conclusions, comics furnished Grooms with ingredients perfectly suited to his natural talent for rapid, unedited drawing. Grooms would combine the high-art aestheticism of French modernist artists, the spontaneous, aggressive draughtsmanship of the Abstract Expressionist painters, and the low-art spectacle, humor, and plain zaniness of comedic movies and comic books.

In 1962, Grooms teamed up with filmmaker and photographer Rudy Burckhardt to make Shoot The Moon, a 16-millimeter film inspired by Georges Méliès’s pioneering 1902 film, Voyage À La Lune (A Trip to the Moon). The film’s preposterously self-important Mayor, played by poet and dance critic Edwin Denby, and two officials, played by Burckhardt and Katz, develop figures that, along with the fireman, and later on the policeman, represent iconic urban images for Grooms. His city is one in which people and buildings are in perpetual motion, all in a constant shuffle of energy. As in Pollock’s paintings or the Baroque compositions of Rubens, the eye is led on a ceaseless chase around the image, with one detail, then another, clamoring for attention. This can be true even when there is a predominant image.

Grooms made two prints which enlarge upon the exalted whimsy of Shoot The Moon’s top-hatted eminences. Self-Portrait in a Crowd (1962, published in 1964) was Grooms’s first etching and his first print commission. It depicts a man wearing a stove-pipe hat, hurrying through a crowded street scene, with activity everywhere within the frame, from the ghoulish countenance at the top left to a little dog scurrying along the pavement. A drypoint from 1963, Parade in Top Hat City, pulls back for a view that encompasses brick buildings near and far, all peopled by men in top hats, with a parade of more top-hatted men marching into the distance under a darkly-etched helium balloon. Leaning in from the right is the star of the show, a young man with spiky hair extending a prominent, dark, top hat. He could be the same figure rushing through Self-Portrait in a Crowd. These are early examples of Grooms’s predilection for inserting images of himself into scenes, whether they be imaginary ones such as these or even, anachronistically, historical or art-historical scenes.

In time, Grooms would come to look upon prints as a way of reaching a wide audience. For the present, he concentrated on his three-dimensional work, which kept getting bigger and more environmental until his City of Chicago installation of 1968 finally established him as a major artist some ten years after his arrival on the art scene. He made prints sporadically, developing a reduced graphic sensibility, with simplified color and blunt outlines, as in Mayan Self-Portrait (1966), Mayan with Cigarette (1966), and The Philosopher (1966). Perhaps his most significant graphic productions of the 1960s were the posters and flyers he ran off as announcements for his exhibitions at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Large for their time, modeled on movie posters, they were gaudy and ambitious statements, often mixing media. As in the films he continued to make (where Grooms would frequently combine live footage with animation) so in these lively posters he would interweave photographic and drawn imagery.

Expressionism of the German and American varieties was also influential on Grooms’s graphic style. The variable perspectives of his cityscapes recall German Expressionist films, but it is in fact closer to home that we find more apt graphic parallels--in the prints of John Marin, for one. In 1913, Alfred Stieglitz published a Marin suite entitled Six New York Etchings. Marin’s Brooklyn Bridge and Woolworth Building No. 2 take as subjects architectural monuments Grooms would tackle in his defining Ruckus Manhattan installation of 1975. Marin’s treatment presages Grooms’s in its skewed angles that evoke the city’s tumult.

Observation and categorization of urban types in public spaces has a long history within fine art, at first marginalized, then gradually accepted. William Hogarth in the 18th century made engravings of fanciful theatrical scenes, as well as his more famous moralistic sequences. In the 19th century, Honoré Daumier used the recently-invented lithography technique as a means of mass communication. His political caricatures were published in popular magazines, but he also made paintings and watercolors based on observation of Parisian types. Baudelaire considered him on a par with Ingres and Delacroix as a draughtsman.

Both Hogarth and Daumier, like Grooms, had limited formal education and worked professionally as artists from an early age. The same could be said of another graphic precursor to Grooms, Reginald Marsh. Although he studied at Yale, Marsh got his real education after moving to New York, working as an illustrator for Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, The Daily News, and The New Yorker. He drew people on the subway, making prints like the linocut Subway Car (1921) and the etching 3rd Avenue El (1931). Daumier, too, in his Types Parisiens series, had done an interior of a bus which featured a pretty girl wedged between a drunk and a butcher.

In his book on Marsh’s prints (2), Norman Sasowsky points out that, while he always carried a pocket sketchbook and also made watercolors and took photographs of subjects that interested him, Marsh did not normally use these studies as actual material for his prints, preferring instead to rely on his imagination to mold his observed material into a new reality. Red Grooms also tends to have a sketchbook near at hand and is wont to take down several versions of a scene in rapid succession. When he comes to making a print or painting, however, he too prefers not to be limited to his sketched observations. Grooms goes much farther than Marsh, creating fantastic scenes wholly free from naturalistic constraints such as perspective and the laws of gravity.

By the late 1960s, Grooms had developed graphic mastery and was moving rapidly towards his mature style. To achieve it, he needed to plunge headfirst into the actual chaos of the city, to move beyond the polite but somewhat adolescent fantasies of early images such as Parade in Top Hat City. The first clear step in the direction that would ultimately lead to a masterpiece such as Ruckus Manhattan was Patriot’s Parade (21 by 32 1/4 inches) (3), the artist’s first lithograph, which he published himself in an edition of 25 in 1967. Quite unlike the storybook air of his earlier parade, which floated gaily into the distance, this parade make a full frontal attack on the viewer. To complement its savage subject matter--the violent fervor of pro-war demonstrators--Grooms created an apocalyptic, shifting scene, in which scale is rudely abused. Larger heads lie frighteningly behind smaller ones, a tiny baby disappears beneath the sole of an enormous shoe, and a relentless filling-in of space adds up to a suffocating feeling that there is no escape. A grimacing, jut-jawed policeman raises a billy club, about to bring it down on an already vanquished peace protester, and in the upper right corner of the print, under a sign reading “NAPALM EM ALL,” a group of paraders marches towards us in stars-and-stripes top hats, and we realize with a sigh that our innocence has ended, that those funny, top-hatted loonies of our youth have retreated to the realm of childhood memories, to be replaced by a reality which, although repellent, can also be energizing.

II. Nervous City

“We want a poem to be beautiful,” wrote W.H. Auden, “that is to say, a verbal earthly paradise, a timeless world of pure play. At the same time, we want a poem to be true, to provide us with some kind of revelation about our life, and a poet cannot bring us any truth without introducing the problematic, the painful, the disorderly, the ugly.” Grooms mastered early on Auden’s “timeless world of pure play.” Before he could move beyond the realm of the merely titillating and become a major artist, he needed to add layers of complexity to his pictures. This he accomplished by introducing the disorderly and ugly. If his subject was to be the city and its denizens, its characterization had to be as complete as possible.

Grooms studied first in Chicago, then in New York. His first major installation was City of Chicago(1968); later, he made Ruckus Manhattan (1975). Perhaps by coincidence--or perhaps by instinct--he always tackled the Second City before going to the capital. The same is true of his mature print work. In 1970, he was asked to take part in a portfolio of Chicago artists entitled 76 artists -- 78 prints. Grooms’s participation was his first silkscreen, printed on glossy poster paper. Its official title is Manic Pal Co. Mix, but a close look at the print reveals the heading actually reads “MANICIPAL CO-MIX,” a Groomsian verbal transformation of “Municipal Comics.” Language in Grooms’s prints often functions as a tongue-in-cheek commentary, while at the same time allowing the potential for confusion, as in this case. Both phrases have relevance, as the image is definitely a mix, an all-over stew of Chicago images, and also humorous, as Grooms, again affirming his appreciation of comic books, gives disaster an approachable spin.

Manic Pal Co. Mix is a direct precursor to Grooms’ first major prints, Nervous City (1971) and the No Gas portfolio(1971), which move to New York for their settings. The Chicago print includes in its margin a wailing firetruck with the comic-book style sound effect “AHRRR,” an image which would reappear in No Gas. It also settles on certain urban types (the fashionable young lady, the crude cop, the hippy, the porn shop habitués) which would become staples in Grooms’s work. The setting too--a public place complete with garbage and sewer systems--would soon become a constant.

Nervous City (22 by 30 inches), a color lithograph printed by Mauro Giuffrida at Bank Street Atelier in New York, was Grooms’s first chance to work in a professional print studio. The difference is obvious, not only in the wonderfully enhanced richness of tones that lithography allows, but also in the controlled composition, in which each figure stands out vividly while simultaneously adding to a powerfully chaotic compositional whole. While it contains many of the elements from Manic Pal Co. Mix, and it continues scalar distortions like those in Patriot’s Parade, Nervous City clarifies such details as the rats scurrying along the sidewalk, a man’s bloodied face, and a leering man injecting a hypodermic needle into the central figure. This female figure is shocking both in the graphic evidence of the abuse she has suffered and also in her current violation, which is the central image of the print. While Nervous City has greater buoyancy in its actual execution than Manic Pal Co. Mix, its picture of humanity is more explicit and sadder.

Grooms’s particular achievement during this period was that of taking a hard look at urban life and showing what he saw there, while not sinking into cynicism or indulging in facile social commentary. In his graphic work, he was developing the vision that would enable him to conceive of Ruckus Manhattan’s various elements and connect them. In his No Gas portfolio of lithographs, while maintaining graphic interest in every part of an image, Grooms moved away from the visual cacophony of Nervous City toward dominant, central, images. The firetruck which appeared in Manic Pal Co. Mix’s margin is now the main subject of the print Aarrrrrrhh. The rat which skirted the bottom of Nervous City looms large in Rat. A haggard, unshaven figure hovers over a huge coffee cup in No Gas Cafe, while an outrageous floozy gets center stage in Taxi Pretzel. The image that looks forward most directly to Ruckus Manhattan, while winking backward at Marsh and Daumier, is Local, a subway interior with a gaggle of extreme characters who will be developed three dimensionally in the life-size subway car of Ruckus Manhattan.

Nervous City marked the first time Grooms allowed sexually explicit subject matter into his work in any medium. It may have had to do with his belief that printmaking could provide an avenue to a wider audience where filmmaking had not. As Grooms describes it, “I don’t know where my raunch comes from exactly. We were like the anti-raunch, when we did Shoot The Moon. We were like these Boy Scouts, doing this movie that had zero sex appeal. I think that raunch was part of my equation to some sort of modernism. I suppose I thought that if I could be out there on the raunch level I could get to some kind of edge.”

In the early 1970s, Grooms began working with professional printmakers in a variety of techniques. 1976 was a watershed year for Grooms’s printmaking; he produced 22 editions, including the two versions of Picasso Goes to Heaven. This image had started as a 15 by 16 foot painting on paper in response to the news of Picasso’s death in 1973. With the onslaught of the Ruckus Manhattan project, Grooms had to leave the Picasso painting unfinished. He made two marvelous prints of the image upon resurfacing from Ruckus Manhattan in 1976. After completing that 6,400 square foot installation, Grooms relished the opportunity to work alone, and prints provided that opportunity. One of the first he did was the lithograph Matisse (1976, 27 by 19 1/2 inches), a detailed and faithful rendering of a famous Brassai photograph of Matisse drawing a nude.

The most significant body of prints Grooms made during the 1970s were the etchings printed by Jennifer Melby. The majority of them continue the sexual undercurrent that first surfaced in Nervous City. Two prints of 1976, Manet/Romance and Heads Up D.H., extend a complexity of grounds first encountered in Manic Pal Co. Mix. In these images, vastly different scales and worlds overlap with a gyrating intensity that prevents the eye or mind from stopping until it has left the image. Included in the mix in both cases are images of a sexual nature. In Heads Up D.H,, in particular, one notices, next to the pensive figure of Lawrence himself, a dominatrix with studded collar and whip. The artists named in the titles figure in both images, and the effect is that of a psychosexual whirl, reflecting someone’s inner fears and desires, accentuated by the fact that there is no realistic ground for the eye to settle on.

For the suite Nineteenth-Century Artists, Grooms’s first and most extensive set of etchings, he was able to delight in the pure power of black line on paper. The prints vary in technique from the openness of Baudelaire, with its expanses of untouched paper, to the dense aquatints in Guys and Degas. In all the prints, an air of erotic play parallels Grooms’s carefree speed and wit with line. In terms of subject matter, these prints are different from the gloomy and dense grounds of Manet/Romance and Heads Up D.H. Rodin frolics in his studio in a pair of women’s boots, Bazille looks at us over the shoulder of a corsetted model, his brushes and palette fallen in disarray, while his naked posterior points upward at an improbable angle. Nadar reprises imagery from the early Parade in Top Hat City, with the difference that now, instead of watching a balloon float away in the distance, we have a close-up view of the top-hatted photographer in the balloon, engaging in champagne-fueled revelry high above Paris.

Rrose Selavy (1980), the last print Grooms would do with Melby, takes up this theme of sexual subplots for famous artists, this time directly referencing a famous photograph by Man Ray of Marcel Duchamp dressed as a woman. A sexual tension also underlies a silkscreen Grooms produced in 1978 with Chromacomp, Inc., entitled You Can Have a Body Like Mine. The overlapping of semi-nude male bodies with those of fully clothed women gives the impression, again, of men in women’s clothing. Cross-dressing in Grooms’ prints, and other sexual themes, are never the entire subject of a print. Rather, they provide visual excitement which, in the case of You Can Have a Body Like Mine, is engendered also by the punchy red background, the abrupt shifts of scale, and the fleet of green cars that careens in the upper portion of the print.

In 1979, Grooms went to Minneapolis to work with Steve Andersen, whose operation was then called Vermillion Editions and is now Akasha Studio. Andersen was a skilled printer of silkscreen, lithography, and woodcut, who liked to combine multiple techniques in one project. In 10 working days, Grooms and Andersen initiated about ten projects. The results of printmaking, especially in the spontaneous way Grooms engages in it, depend to a great extent upon the personal interaction between artist and printer. “Steve is a guy who has no qualms about using the most elaborate approach,” Grooms explains. “To get the work the way it should be, the way the artist wants it to be, he will bend over backwards without any concern for time or expense. He’s very good at improvising and picking up in any which way the thing lands.”

They conceived of a portfolio to be entitled Sex in the Midwest and prepared the lithographic stones. Ultimately, however, prints were issued separately, not as a portfolio. The first two to appear were Lorna Doone (1980), a large print on two sheets featuring a New Wave girl in a leopard-skin jumpsuit lounging in a Midwestern field, and The Tattoo Artist (1981), which shows a redheaded man, naked except for ladies’ stockings, garter, and stiletto heels, getting a tattoo from a similarly-dressed lady. A much more intricate piece, Pancake Eater, was editioned in 1981. It started as a simple lithograph, but as Grooms had already produced two fully three-dimensional prints by then, he and Andersen decided to give this one a more lavish treatment as well. It ended up being a three-dimensional box depicting a house, with a Mylar sheet printed with silkscreen images of a whip, boots, and lace curtains. Then came a standard vinyl window shade, on which was silkscreened a silhouetted image of a lady with a whip and two slaves. After one lifts the shade, one finally gets to see the lithograph, which shows the eponymous pancake eater, an elderly lady, fully-dressed, being served by two young bare-chested men in collars and chains.

Two lithographs from Sex in the Midwest were editioned only very recently, although they were part of the original group whose stones were drawn in 1979. Rosie’s Closet was published in 1997, and the Sex in the Midwest title sheet was published in 1998. Times have changed, and alterations to these two images prove the social climate is not as tolerant in the 1990s as it was in the 1970s. Rosie’s Closet is a charming, rather large (34 by 25 1/2 inch) print, depicting two women engaged in a game of doctor in a closet filled with hats, shoes, a Clue gameboard, and a toy railroad train (a phallic image Grooms had already used in Heads Up D.H.). There is nothing vulgar about the image, and the expression of the woman facing us is one of Grooms’s most delicate evocations of female beauty. However, it was determined that the stethoscope placed over her frontally exposed vagina was too disturbing an image, and for the 1997 version a collaged panty has been inserted. The revision for Sex in the Midwest, originally meant to be glued onto a portfolio cover, is even more direct. Across the midsection of a naked couple embracing in front of an open window, a large black bar has been silkscreened with the word “CENSORED.” Two other images remain uneditioned, while an additional two stones have been destroyed.

In the 1980s, Grooms would move into a new phase, dominated by three-dimensional prints and images from modern art history. Grooms would treat the city again, but it would not be the New York of Nervous City. In 1983, in the serigraph Saskia Down the Metro, Grooms even referenced his own work, including seated figures taken from his subway installation in Ruckus Manhattan. While the print is graphically interesting, it has an air of nostalgia about it. Danger has been modulated. Grooms’s period of sexually explicit subject matter had also come to an end.

III. Making History

After the early linocut Five Futurists (1958), which both played on recreating photographic imagery in a hand-done technique and referred to a group of real, historical artists, we have to wait until the mid-1970s before encountering Grooms’s next prints of historical subjects. The overwhelming number of artists Grooms has chosen to depict are French, indicating that French modernism is a leading source of his inspiration. Picasso Goes to Heaven (etching and pochoir, 1976, 23 5/8 by 23 7/8 inches, color and black-and-white versions) is a complicated image. As Picasso rises on a swing, he is surrounded by a coterie of artist-associates, including the Douanier Rousseau, Gertrude Stein, Cézanne, Stravinsky, Apollinaire, Braque, Laurencin, Max Jacob, Matisse, Diaghilev, and Nijinsky. True to Grooms form, he complements these contemporary personalities with figures from Picasso’s paintings and a group of old masters.

The only large-scale woodcut Grooms has ever done, and his largest print in any medium, is The Existentialist (1984, 72 1/4 by 42 inches), published by the Experimental Workshop in San Francisco. The subject is Alberto Giacometti, whom Grooms remembers seeing in Paris in 1960. He evoked the same postwar Parisian ambiance in Cafe Deux Magots (1985, published in 1987), which emerged from in his first session with the master French etcher Aldo Crommelynck, who printed extensively for Picasso. The Deux Magots was an important meeting place for many of the people featured in the print. The actual combination of all these personages at one time--not to mention the spatial distortions that enable Grooms to show everybody simultaneously--sprang directly from the imagination of Red Grooms. The scene, which comes with a legend identifying Brassai, Giacometti, Camus, Françoise Gilot, Prévert, Juliette Greco, Cocteau, Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir, among others, was the result of a research effort not uncommon for Grooms, carried out this time by Grooms’s wife, Lysiane Luong and her Parisian family.

In 1988, Grooms made a color lithograph entitled Van Gogh with Sunflowers, printed by Bud Shark, with whom Grooms began working in 1981. Grooms’s masterful drawing technique is well-suited to lithography, and in this print his sequential marks pay homage to one of Van Gogh’s techniques. Another color lithograph from Shark is Grooms’s Matisse in Nice (1992), a good-sized (22 1/4 by 30 inches) interior showing Matisse painting a nude. With only eight colors, artist and printer have created the impression of a rich panoply of tones. The bravura performance of Grooms’s drawing in the two paintings within the print, the letter on the coffee table, and other details is matched by the precise application of tones.

From the School of Paris, Grooms moved to the New York School, developing unusual techniques in emulation of the formal inventiveness of its artists. He made De Kooning Breaks Through (1987) and Jackson in Action (1997), two three-dimensional prints done with Bud Shark; Elaine de Kooning at the Cedar Bar(1991), a stratograph printed by Joe Wilfer; and The Cedar Bar (1987), an offset lithograph printed by Maurice Sanchez and Joe Petruzelli of Derrière L’Etoile Studios. This last piece is based on a photograph of a large maquette Grooms made of the famous bar where artists congregated in the 1950s. One can make out De Kooning, Pollock, Guston, Rothko, and Newman. Following his predilection for mixing media, Grooms made new drawings of Mike Kanemitsu, Theodore Stamos, and others, which were printed together with the photographic image of the maquette, creating a juxtaposition of esthetic realities, and an abrupt juncture between background and foreground.

Grooms has also made prints that have contemporary artists as their subjects. During his great homage to Nineteenth-Century Artists in 1976, Grooms felt moved to include his friend Rudy Burckhardt in the series and made the etching Rudy Burckhardt as a Nineteenth-Century Artist. Since Burckhardt was born in 1914 and exuded old world charm, it did not seem like such a stretch. Two prints from 1980, which combine etching and aquatint, feature contemporary realist painter Jack Beal. They are Jack Beal Watching Superbowl XIV and Dallas 14, Jack 6.

Into this sprawling and ever-expanding set of heroes and superheroes, Grooms has often insinuated himself, a red-headed figure in the background. He has also made self-portraits in different print media, going back to Self-Portrait in a Crowd. More recent examples include Self-Portrait with Mickey Mouse (1976), a harrowing, crudely-hatched view of the man who had just finished running the marathon of making Ruckus Manhattan. Red Grooms, Martin Wiley Gallery (1978) goes back to the gallery posters he did in the 1960s, combining photographic and drawn images. Self-Portrait with Liz (1982) is a look in the mirror, based on a watercolor, while Red Grooms Drawing David Saunders Drawing Red Grooms is a conceptual lithograph, featuring Grooms and his former assistant, artist David Saunders, shifted to different perspectival axes within the same print.

Increasingly, in the 1980s and 1990s, Grooms would look to technical challenges as a motivating factor, while constantly mining his fascination with historical figures and the question of the artist’s own position as a practitioner of traditional and untraditional artworks. He no longer seems affected by the danger the city may provoke. From a calmer, more worldly point of view, the artist gazes upon eternity and smiles.

IV. Three-Dimensional Prints?

How did Grooms ever arrive at the idea of bringing the staid, stable, two-dimensional print into the arena of sculpture and pop-up books? “When I was a kid,” he explains, “I used to make model airplanes out of paper. I got them in a kit which contained a simple page, a flat sheet with tabs, and you cut them out and glued them together. Actually, old toys were made exactly like these three-dimensional prints. They were printed on tin sheets and then cut out and assembled.”

The immediate impetus for the three-dimensional prints were paper sculptures Grooms made in the early 1970s using a hot glue gun. Grooms is naturally attracted to a sculptural aesthetic. He also likes to combine media, blurring traditional distinctions. In that sense, his extensive foray into three-dimensional printmaking is akin to the Cubists’ modernist innovation with collage. In both cases, a conceptual development from technical experimentation led to a new form. Grooms’s first attempt to go beyond the flat sheet in printmaking was in the lithograph Aarrrrrrhh from the No Gas portfolio, which includes a firetruck that folds away from the surface of the print. His first fully three-dimensional print, however, was Gertrude, printed by Mauro Giuffrida at Circle Workshop in 1975, two years after his discovery of the glue gun. Gertrude was composed like a tab toy, printed on a flat sheet, with sections to be cut out and tabs to be inserted.

When Grooms next wanted to do three-dimensional prints, he turned to Steve Andersen. Their first three-dimensional piece was Peking Delight (1979), a wall piece like Gertrude, as opposed to some later three-dimensional prints, which are free-standing and can be seen from all sides. Peking Delight is handpainted and printed in 21 colors, using pochoir stencils, silk screens, and rubber stamps. Unlike Gertrude, it is made of wood, to which the colors have been applied. Grooms and Andersen then made Dali Salad (1980) in two slightly different versions. Dali Salad bears the mark of Steve Andersen’s careful complexity, combining lithograph and silkscreen on two types of paper and vinyl, with Ping-Pong balls for the eyes. The hair is simple black Arches paper cut to Grooms’s specifications. The moustache is painted aluminum.

Grooms and Andersen have recently teamed up on another blockbuster, Katherine, Marcel, and The Bride (1998), which depicts, three-dimensionally, the home of Katherine Dreier, the famous collector, with artworks by Brancusi, Duchamp, and Leger. This time, 130 separately editioned colors were silkscreened onto an elaborate support structure of board, cut by laser and assembled by hand. It took over four years to complete and is yet another example of Grooms’s love of theatrics and showmanship.

In 1981, Grooms made his first print with Bud Shark, a lithographer who also works in woodcut, marking the beginning of what has become Grooms’s most prolific relationship with a printer. Grooms’s first print with him, Mountaintime (1981), although not fully three-dimensional, already contained paper and string additions that took it beyond a simple flat sheet. The following year, they made their first three-dimensional print, Ruckus Taxi (1982). Grooms’s first free-standing print, it comes in a Plexiglas box and can be viewed from all sides. With only five colors, they managed to capture the excitement of Grooms’s early city work and reference a huge walk-in taxi created for a revival of Ruckus Manhattan.

Among their other three-dimensional prints, Grooms and Shark, who co-publish many of their efforts, have done a bullfight, a cut-away subway train, and a basketball player, who rises high above everyone else in the scene to dunk the ball. Then there is the remarkable De Kooning Breaks Through (1987). Its conceit is to have the artist physically breaking through his canvas of Woman and Bicycle by riding a bicycle through it, thereby making literal his smashing of the prohibition among Abstract Expressionist painters against painting illusionistically (or “penetrating the picture plane”).

The most spectacular three-dimensional prints by Grooms and Shark are three of artists. South Sea Sonata (1992) shows Paul Gauguin making an ink drawing in Tahiti. The artist’s large head dominates the scene, a little ponderously, while a two-dimensional backdrop reveals women in the back of a grass shack. The relationship of head to body to room is more lively in the recent Picasso (1997). In this piece and another from the same year, Jackson in Action (1997), Grooms has reached a new level of execution. Picasso uses only six colors, printed on two sheets from ten plates, and comes away with astonishing details such as the lighted cigarette, the owl sculpture, and the mandolins and paintings hanging on the wall. The relationship between the body of Picasso and the background is perfect. The same is true in Jackson in Action, despite a much higher degree of compression. The latter image includes the stop-frame effect of Pollock in different positions with dripping paint and actual paper versions of those famous skeins. The figures of Lee Krasner in the doorway and Rudy Burckhardt photographing Pollock round out this terrific scene that draws upon the energy that inspired the Happenings.

V. Collaboration

The work of a master printer is identifiable from artist to artist. When an artist is happy with a print, he signs it. The story of printmaking is the story of people working together to achieve a common end. Red Grooms has relied on collaboration since early in his career, first in performances, then films, then in huge installations, and also in prints. As Grooms has pointed out, the chemistry between an artist and a printer will determine what types of projects they will undertake together. One printer will encourage outrageous subject matter. Another will propose a new technique. Another will give plates to the artist to take home and do with whatever he will.

Chromacomp, Inc., was a silkscreen printer Grooms worked with from 1971 to 1978. They produced some of Grooms’s most vibrant prints, including Mango Mango (1973), Bicentennial Bandwagon (1975, published in 1976), and You Can Have a Body Like Mine (1978). For the first two prints, Grooms, wanting to expand technical possibilities, made a maquette using cut-out pieces of brightly colored paper. Its effect is apparent in the floral patterns on the woman’s dress in Mango Mango and a squared-off quality to the lines. Mango Mango was a large print for the time at 40 by 28 3/4 inches. Bicentennial Bandwagon is only 26 1/2 by 34 3/4 inches, but it seems larger because of the graphic punch it packs, partially as a result of the cut-paper technique and partially because the print is a compressed version of the maquette, which was about twice its size. Echoing the cut-paper original, the figures seem to be two-dimensional, free-standing cut-outs, with the grass behind them a flat, as in a stage set, and the active sky a further backdrop. The print gains much of its dynamism from the baroque nuance of detail, reminiscent of Grooms’s New York City street scenes. There are hints of the sexuality we have observed in other Grooms prints from this period in the phallic red rockets bursting and the outrageous platform pumps worn by the bearded figure (presumably male) riding a big-wheel bicycle across an impossible tightrope, suspended from a bamboo pole and a detached architectural dome. The vehicle on which all this activity takes place is a faithful if improvised version of a circus bandwagon, an example of how Grooms combines historical accuracy with ludic fancy.

Grooms did 27 prints with Jennifer Melby from 1973 to 1980, most of them black and white etchings, some with aquatint. One of their later pieces, Coney Island (1978), was an aquatint in four colors. It is the only print in which Grooms has taken on the locale that so appealed to Reginald Marsh, who reveled in the Baroque quality of the place “where a million near-naked bodies could be seen at once, a phenomenon unparalleled in history.” Grooms was more attracted to the carnival atmosphere. He had tackled the subject before in the cover art he did for Richard Snow’s poetry book The Funny Place (Adventures in Poetry, 1973). There, he had been in the thick of his Nervous City mode and drew a dense tableau of disparate types jammed together in suffocating proximity. For the print Coney Island, Grooms went back to the overlapping grounds he had realized in Manet/Romance and Heads Up D.H. and gave them a whirlpool figuration, inspired by rides at the amusement park.

In the early 1980s, Grooms made three silkscreens with Alexander Heinrici. For Fred and Ginger (1982), Heinrici gave Grooms a special paint that would adhere to clear plastic Mylar, enabling Grooms to make the color separations himself, which he found liberating: “That was good because I could get out of this trap where the print is a reproduction of a work. In lithography, it’s so hands-on; you’re actually drawing on the stones or plates and doing the color separations yourself. That’s going to have an immediate effect that’s different from when somebody does a reproduction of a work, which was usually the case with silkscreen.” Grooms also used the Mylar on his next print with Heinrici, Franklin’s Reception at the Court of France (1982), drawing with pencil and bamboo pen. These prints have a lively appeal similar to that of Bicentennial Bandwagon, even though they were arrived at differently.

After working with Aldo Crommelynck in Paris in 1985, Grooms looked forward to another chance, which arose when Crommelynck had a studio in New York in the 1990s. They did a series of eight etchings with aquatint based on Grand Central Station, a topical subject since the installation of Ruckus Manhattan there in 1993. Their major effort was a rich-toned color etching, Main Concourse Terminal, Grand Central Station (1994). They also did a set of six smaller etchings on related subjects. In one, we see the master printer Crommelynck at work, a thickly outlined form sketching with a compass on an etching plate to describe the precise arc of the Main Concourse ceiling, while in the background an imaginary ruin extends, full of similar arches.

Grooms got to work with Joe Wilfer before his untimely death and made two unusual prints, Elaine de Kooning at the Cedar Bar (1991) and A Light Madam (1992), using Wilfer’s stratograph technique of building up paper to form a relief surface similar to a woodblock. Where a woodblock often reveals the texture of the wood, a stratograph reflects the more muted texture it receives from the paper, which suits the darkly-lit settings of these subjects.

Epilogue: Marginalia

Printmaking for Grooms began in making gifts for friends. Later, it became a vehicle to disseminate his vision of the city as a site of invigorating chaos. Finally, it provided an opportunity to work with master craftsmen and to align himself with great artists from the past. Recently, he has made prints in the margins of his three-dimensional sheets--marginalia, which he improvises in the print studio. Liberty Front and Back (1998), a color woodcut on rice paper no bigger than a postage stamp, has the informality of Grooms’s earliest woodcuts. He keeps devising ways to refresh techniques, working at breakneck speed, molding and reshaping the world he sees.

Notes

1) All quotations of the artist are from interviews with the author during June 1999.

2) The Prints of Reginald Marsh by Norman Sasowsky (Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1976)

3) All measurements in this essay refer to image size, which may differ from paper size.