_____Katz saw his own work in terms of music and athletic enterprise, and he saw it as taking an aggressive aesthetic position. He speaks of the “five audiences” -- other artists, the general public, museums, collectors, critics -- and the necessity of reaching those audiences. He values vision over technique, yet his own technique is impressive, an aptitude developed from childhood with single-minded voracity.

_____There is an unnerving quality to a lot of Katz’s paintings. Sometimes, it is the claim that there can be this much beauty in the world, that this is real. Can women be this stunning, this full of flesh and color and grace? Then we go out and look at them, and find they are. Our seeing has been colored by the paintings; they have caused us to see differently, to see more.

The new flowers overwhelm us -- first by their color. A rose cannot be that pungent, a marigold that full of light, but they are. A live rose petal has few equals for vivid pigment. There is something surreal about the way painted the roses sit in space, most of them unconnected to stems, in close proximity to the man-made geometry of a cast-iron fence. The gestures of the roses, their attitudes, are precise. This tension is typical of Katz -- not all details are filled in, while veracity of color and gesture lead the eye convincingly. The drawing within the roses is great linear painting. The lines that seem so large up close, from a distance snap into place as flowers’ shadowed contours. The drawing of the marigolds, by contrast, is delicate up close and barely decipherable from afar.

_____ Katz uses systems when he draws -- systems for drawing eyes and lips, systems for drawing the pistils of flowers. The systems create patterns, and the artist remains alive to the stroke even while painting a repeated pattern. If one compares different paintings of the same flowers, one sees that Katz carefully varies the background tones and textures, the distances from which the flowers are seen, and the overall light.

_____Katz is meticulous in decisions of canvas size, cropping, and proximity. In order to prepare for a painting, he works in stages. He starts with small painted studies on board, done face-to-face with his subject. He synthesizes compositional and tonal elements from a series of studies, decides on the format for his oil on canvas, then draws a cartoon in charcoal on paper. This is a critical stage, at which he refines and defines the compositional strategy for the painting. Transferring the charcoal drawing to the primed canvas, he is now ready to paint. Having mixed colors based on an analysis of what worked best in the studies, he embarks on the painting, usually finishing in a single day-long session. While he is making it, the painting acquires its own life, as his translations and predictions take on realities and qualities of their own, to which the artist reacts. He builds up grounds, then quickly paints into them, leaving traces that feel inevitable as they do casual.

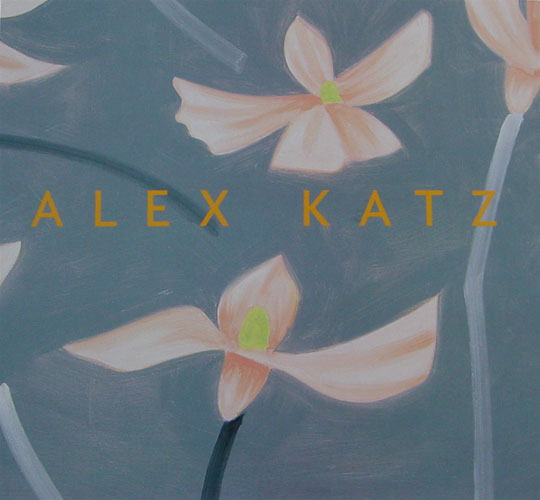

_____The word “flat” has been used on occasion to describe Katz’s backgrounds or other expanses of color. If one examines the backgrounds of these flower paintings, one finds them anything but flat. They are as active with gesture and incident as the painted flowers themselves. Often, as in Impatiens and Magnolia, the ground is brushed around the flowers’ forms, creating eddies and passages that contribute to the liveliness of the entire painting and also keep the flowers themselves in motion, by preventing the petals’ edges from becoming static.

Some critics have been most affected by what they see as the apparent tension in Katz’s work between abstraction and realism. That Katz came of age during the heyday of abstract painting in this country might seem to argue in favor of the artist’s having intentionally adopted a controversial position of being neither one nor the other, but both. In a painting like Spring Landscape, one can imagine one sees elements of Color Field, all-over abstraction, and irregular gridlike forms. While it is true that Katz’s realism is as far from the Sunday painter’s as is the work of any abstract painter, Katz is still deeply concerned with the act of seeing the world around him, whether that world consists of a mundane interior, a glamorous party, or an unidentified patch of nature.

_____What is each time more surprising, as Katz’s art and technique evolve, is his particular way of translating a vision into paint. Road takes up an image Katz has painted since early in his career. In the road painting in the current exhibition, one senses that Katz, at this point in his painting life, has so internalized facts of seeing that it is second nature for him to paint the angle of light snaking across a shadowed road in such a way that it not only lies down but also spreads in the way that light, when we see it on a summer day, spreads, not limited to a precisely carved-out space.

_____The real thrill for Katz must be in the actual painting. He consistently poses himself new technical challenges, and his technique continues to expand. What he sees also changes. In his recent paintings, the vision is not somber but light. The darks, as in Road or Green Shadows, are lush, not ominous. Two tree paintings, verticals, might stand for the entire exhibition. Birches lifts in a shimmer of leaves, one curving branch reaching down to touch a nearby limb. Grey and Green explodes in a manner we never would have imagined, a burst of nature as paint.

_____The paintings should be shocking to painters, as examples of tour-de-force painting the like of which is hard to find among contemporary artists. There are a handful of painters working today who take advantage of paint’s potentials, as opposed to drawing in paint, and Katz is among them. He exploits the natures of different pigments on smooth surfaces, allowing specific depths to appear.

In his 1960 lecture, Katz spoke of a “curious paradox,” namely, that one could achieve immortality, or timelessness, in a particular, absolute, moment. Painting was a way to achieve that state. It could be an attempt to access subconscious symbolism, such as Miró had explored, or it could be the discovery of a technique, such as Pollock’s, so quick that it precluded premeditation, at least before it congealed into a manner. Another kind of automatic painting was a more traditional one, painting nature. “Nature is always changing, always in motion,” Katz said. “The light changes, and your eyes change. That produces a state that is close to automatic painting. You can’t think fast enough to keep up with it. You get ahead of the conscious part of your mind a little bit.”

_____Landscape painting was the final element that enabled Katz to arrive at his mature work. He had already abandoned the modernist systems he had learned in art school, in an attempt to get beyond the Cubist approach that pervaded advanced art-making in the 1940s. It was during a stay at Skowhegan, as a student, that Katz first began the discipline of daily painting outdoors, an activity he would continue for many summers. By the early 1950s, he had developed an adept approach to landscape, sometimes airy, with delicate wisps of branches or stems, sometimes blockier, with patches of color serving as land forms. In the mid-1960s, having already painted his iconic large portrait heads, Katz embarked on a series of flower paintings that presented the flower, too, as a towering, monolithic subject. Part of the impetus behind the flower paintings was an attempt to present flowers in a way that was not still life, and also not patterns in a field. They are seen from an extremely close vantage and even when blown up to 6 feet high, they feel life size. The flowers’ volumetric qualities were accentuated by highy cropped compositions.

_____Landscapes rejoined the center of Katz’s preoccupations following his retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1986. Again, he wanted to try for a different kind of viewing experience, one in which the space would envelop the viewer. He achieved this first in views of New York City and then in scenes of nature. Many of the nature views are set in Maine, where Katz summers, but some, such as a 20-foot painting of apple blossoms, are actually highly selective snippets of the urban setting. Katz has also left ambiguous the settings of some of his recent portraits. Often, when an elegant figure appears in front of a beach, it is because that person was posing in front of a Katz beach painting.

_____ Flowers have crept back into the Katz corpus more recently, also occasionally serving as portrait backgrounds. This very summer, up in Maine, Katz has been working on a series of Yellow Flags, seen among tall grass in front of a dark brown brook. A casual glance around his house reveals a vertical oil on board from the 1960s of the same flowers. Day lilies and tiger lilies have appeared throughout the years, as they are a perennial part of Katz’s summer setting. The current paintings represent an active attack on the idea of the flower, one that partakes of the environmental aspect of his large nature scenes.

_____Katz’s parents were strong formative influences on the painter’s aesthetics and thinking. His mother, an actress who later ran a theater and championed political causes, followed her son’s career. Katz’s mother had in her papers some clippings of Katz’s early reviews, including one by Fairfield Porter, who wrote in The Nation in 1960, “[Katz] does not need to say that the deepest reality is in visual experience, or in the paint medium as the medium for nature, or in communication, or emotion, or the image, or in art as aesthetics -- the ivory tower.” Porter saw Katz’s work as being aware of a range of aesthetic and human experience, and capable of achieving a balance in which no particular facet was given undue weight at the expense of any other. Porter also picked up on a singular aspect of Katz’s work, its involvement with emotion. Katz himself alluded to this in his 1960 lecture, when he spoke of the ultimate aspirations for the artist: “Style comes from a person being himself and being in tune with the time he lives in. If it doesn’t come from the total person, or the person’s total experience, it’s conventional and arty, and just the opposite of artistic.”

_____According to Katz, the easiest thing for an artist to do is to develop an identifiable affect, what he refers to as “handwriting.” The next level up is the ability to create a memorable image. After that, it is an image with presence (“people can look at it, and they take something away with them”). The final level of accomplishment is when the artist has a vision: “Then people see art and see the world through your eyes, and that’s real style.” The absolute in art is not so much for the observer as for the artist. The artist achieves a moment when he is fully in the present tense and creates work that partakes of that emotion. Then, it gets translated to the viewer: