home | books | poetry | plays | translations | online | criticism | video | collaboration | press | calendar | bio

| Art Books and Catalogues | Curatorial | Poetry | Translation |

|

|||

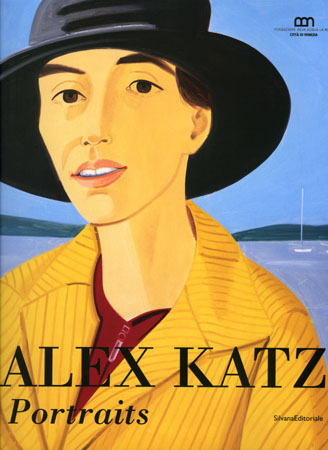

| Alex Katz Portraits, 2003, Silvana Editoriale, Milano, Italy | |||

|

Exhibition “Alex Katz Portraits” at Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa curated by Vincent Katz It could be good to begin with some words. Words are not objects but pathways, leading back in time and forward, not fixed but moving. They are also not units, but like machines, complex mechanisms, tools that can benefit us or fall dull from mis-use. The following words, along with some examples, may help us think about what a portrait is. These particular pathways come from The Oxford English Dictionary, a work of literature delicately tied to its time. The following may help us think about what an artist does when he makes a portrait of someone. Portrait [medieval Latin protractus plan, image, portrait, from protractus, past participle of Latin protrahere] Portray [Latin protrahere, to draw forth, reveal, extend, prolong, in medieval Latin also to draw, portray, paint, from pro-forth + trahere-draw.] Draw I. Of traction. II. Of attraction, drawing in or together. III. Of extraction, withdrawal, removal. IV. Of tension, extension, protraction. V. Of delineation or construction by drawing. VI. reflexive and intransitive Of motion, moving oneself. VII. In combination with adverbs (e.g. draw out). It seems by following words -- and we could keep going, pursuing “design,” “delineation,” “paint,” “picture” -- that eventually we can get to the bottom of this, but we cannot, only in terms of words, which pursuit interests us, as writers, and people who use words, to be able to say clearly what it is we think about a work of art, but it does not get deeper into the work of art. There are technical descriptions, that get part of the way, and theory, which is usually limited by its attempt to secure acolytes. Following words is a pleasurable way, and not without merit. To think about the portrait, I have attempted to dredge the meanings of the word. Literally, “portrait” comes from the Latin word meaning to drag or draw something along, the same root meaning for our word “draw,” so dragging something across a surface results in a picture. There is additional resonance in the case of a portrait, coming from the Latin protrahere: to draw, drag forward, especially to drag forth from a place, leading to (1) to bring to light, reveal make known, (2) to compel, force, (3) to drag on, protract, defer. A portrait then is “something revealed.” That may be a good point of departure for thinking about portraiture. What is it that is brought to light by a portrait? What distinguishes a portrait from a picture of a person that is not a portrait? We shall leave aside an extended definition, that results in such valid conceptions as “portrait of a tree,” “portrait of a house,” etc. It has been thought at certain, though not all, times that a portrait is supposed to reveal something from a person’s recesses, something hidden in normal life, not available to surface perception. The portrait, in a psychological age, could reveal the supressed torments of the psyche. In an age less concerned with psychology and more concerned with status, a portrait could be thought to reveal determining facts about a person’s social standing and power. In ages in which religion plays a dominant role, a portrait could reveal basic truths about a person’s vital relationships to all-powerful gods. In different ways, portraits reveal something about a person’s perceived position in the universe. The source of the perception varies too according to the epoch. In ages when depiction is strongly controlled by social and economic forces such as religious and secular powers, portraits work in the manners thus determined. In ages when patronage dissipates and artists work with less security and more freedom, the artists themselves have more control over the defining signs and symbols in their portraits. “I see a difference between signs and symbols in painting. A sign is read and the meaning is singular. A symbol is perceived and ambiguous. To function, a symbol must be part of high style art. A symbol must do many things simultaneously, while having but one image. A high style makes an image that is multiple. The head of Nefertiti is a good example. It is a specific woman. It is a beautiful woman. It is realism. It is an aristocrat. It is elegance. It is mother. It is queen. It is power. It is a god. It is steadfast and unchanging and therefore, security. It is fleeting beauty. It is the unattainable. The style enables the image to move gracefully from one idea to another.” That account of the multiplicity of symbols, given by Alex Katz in his “Talk On Signs And Symbols,” delivered at the General Meeting of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 23 April 1977, holds the key to his ambitions for all his pictures of people and particularly his portraits. The portraits, focused as they are on individuals, lend themselves to this game of multiples, in which everyone is enriched -- the artist because his work does not deaden into a known quantity, the viewer because the work is always changing, always alive. When Katz began painting people, in the mid-1950s, he used photographs as sources, and made paintings of people posing, usually with faces devoid of features. All that was left was the emotion of the pose, the closeness of family or friends momentarily grouped, demonstrating their solidarity, however fleeting. In 1957, after meeting Ada Del Moro, whom he would soon marry, Katz became interested in the possibility of making a likeness of a specific person. The portrait in the 20th century, like the sonnet, had been, if not officially declared dead, at least left for dead among those involved with the most advanced modern art, but just as Edwin Denby and Ted Berrigan would reveal that the sonnet indeed had tonic life left in it, Katz saw a way to make portraiture vital in the 1950s. Katz titled his art education memoir Invented Symbols pointedly because he believes in the importance, for the artist, not just of working with symbols but of finding his own (“Prometheus. . . inuented the natural pourtractes with the fatte earth.”) In working toward an idea of a contemporary portrait, Katz tried to move from the generalized emotions of his early photo-portraits to a specific image of a person that would also imply a specific moment of a day, in a specific light. Paradoxically, once he succeeded in getting the individual person right, then he was further along the path he had initially started on, namely that of creating a personal image with multiple ramifications. “When you made it figure and environment in a real clear way, it had a way of abstracting into a more generalized statement. The particular person became A Woman.... I figured if I could paint a particular subject, it could be both specific and universal. It could be a certain person and a generalized woman.” “People think realism is details. But realism has to do with an all-over light and having every survace appear distinctive.” “A double portrait is three or four times as complicated as a single portrait. You have to decide who’s going to look at whom, how the figures will relate to each other as well as to the viewer. Are they going to face the viewer, totally passive like pieces of cucumber? ...Most painters in the 20th century treat people as vegetables: they just plunk ‘em down and paint ‘em.” VK: Why do you choose the people you choose for your paintings? AK: They are usually suitable for the social types I’m interested in portraying. I want to do an old man, a pretty girl, a beautiful woman, a romantic couple, etc. VK: There are many well-known art personalities in your paintings. AK: I started out painting my friends, and none of us was particularly famous. It’s a segment of society I live in. I don’t think of one person being more famous than the next. They have a particularness, but I’m also interested in a general type. The image is multiple in reference. VK: What aspect of your work do you feel has not been adequately addressed by critics? AK: In general, people have minimized the optical quality in my paintings. They’ve stressed the formal or social qualities. The optical element is the most important thing to me. That the paintings actually have to do with seeing. It has to do not with what it means but how it appears. There was a moment in history when the Western portrait became personal. Just as poetry could suddenly be directed more precisely at a contemporary and describe settings in ways that we today find modern, so portraiture abandoned the realm of the ideal, of humanity as a generalization, to try to show what an actual person looked like. This process must have evolved gradually, but it can be fairly called a Roman contribution and the beginning of portraiture as we think of it. From the beginning, portraiture served a social function, and patrons wanted some degree of control of their depictions, particularly in the cases of the most public figures. Yet, the flip side usually held, that the person now wanted his individual traces recorded, no matter they might look sullen or mean. paintings as family pictures/poems to people (Personism) In selecting the paintings for the current exhibition, I was aware that some of Katz’s paintings of people have more of the quality of portraits than others. The nudes, for instance, have more to do with ideas of the nude, the nude in art history, and the look of different kinds of light on different kinds of flesh, the shapes that appear, than they do with presenting a portrait of a person. Again, a man with a basketball is more about the idea of an athlete, dynamic motion, a kind of American type, than it is a portrait. The portraits could be full-figure, or they could be zoomed in to show only the subject’s face. They could have a single subject or more than one. The key seemed to be that the portraits do use the personalities of the subjects as a jumping off point, given the facts that likeness in a literal sense is not a prime concern and that the individual was often chosen precisely because he or she could lead to multiple interpretations. Through the years, my father has painted many portraits of me. My mother has been his most frequent subject, and he has painted my girlfriends, my friends, my wife, my dogs, and my two sons. I used to think of these pieces primarily as works of art. I could see them objectively, in the same way that I could refer to my father as “Alex Katz.” But there is always a subjective side as well, at least for the subject, and I think for the artist too, these pictures of the segment of society he inhabits do ultimately document, and preserve for all of us, a record of connections. Perhaps the greatest group portrait he has done, the large-scale cut-out piece One Flight Up (1968?), as well as being a dynamic flow of visual information, is also a remarkable social document of a world of young painters, dancers, poets, curators and critics. Some of the paintings are indeed family pictures. My mother cried recently when the painting Vincent And Sunny (1967?) was taken down from the wall next to the elevator in my parents’ loft. Partially, she was crying because we always thought of it as on of our paintings, in the sense that they stayed around the house for so many decades because only a handful of people thought they were anything more than light entertainment. I guess they mistook charm for unimportance. That mistake is a grave fault in human nature. |

|||