|

Hunt Slonem: Discoverer of Pleasure

By Vincent Katz

Hunt Slonem came of age in an epoch that now seems historic. Whereas many younger artists are making art through mechanical means, downloading or scanning pictures, receiving images for their pieces from mass media, Slonem belongs to a generation that put greater value on personal manual input from the artist and found its sources by personal observation and by searching far and wide in diverse locales. Travel was considered indispensable, partly to put the artist in direct contact with physical works of art. Slonem has devoted himself to the practice of oil painting on canvas and is a significant contributor to its continued vitality.

When Slonem moved to New York in the mid-1970s and began to be a serious painter, it was a period during which Modernist orthodoxy was being challenged. A number of artists began, or continued to, pull elements from a variety of locations and historical times. Artists of the ‘70s and early ‘80s who were displaying synthesizing tendencies included Francesco Clemente, whose work combined classical and popular Indian images with figures from Neapolitan frescoes, Eric Fischl and David Salle, who painted the figure in unabashedly illusionistic manners, painters like Dan Friedman, Richard Bosman, and Nancy Spero, who painted figures in self-consciously rough techniques, Philip Taaffe and Peter Halley, who worked with found or created patterns, and Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, whose first work was done on building fronts and subway walls. Critics gave names to these tendencies, calling them Neo-Expressionism, Neo-Geo, Graffiti Art.

Simply to take elements from diverse cultures, however, and put them together is not sufficient for making interesting art. An artist must have an original insight into a style and must combine that style with other styles in a way that creates a new coherence. Hunt Slonem’s art has been highly influenced (one wants to say “excited”) by periods and tendencies from other times and places. He has been affected by particular buildings and spaces. These elements come together to form his take on ambitious twentieth-century painting.

The diversity of his sources is a sign of his times; the choices are his alone. Some of Slonem’s earliest paintings were of Latin American saints. He also painted arrangements of Incan gold objects, viewed up close but painted large, giving them a massiveness similar to Janet Fish’s 1960s paintings of vegetables or bottles. He has painted Christian angels from the early days to the present. Birds have provided a major slice of Slonem’s visual symbolism. Hindu, Buddhist, and Catholic imagery have been equally important in his work. There has been a Victorian, Neo-Gothic, vein in his lifestyle that has found its way into his work. Then there is his fascination with the occult. Through sessions with mediums, Slonem says he has contacted Rudoph Valentino and others from his circle, such as the actress Nazimova and the Countess Xacha Obrenovitch, all of whose images have served as models for his paintings.

Slonem has something else that attracts followers of art: the allure of myth. He is well-known, and not only in the art world, as the artist who has lived for decades with hundreds of tropical birds in large cages in his lofts. He is also a traveler, in several senses of the word — someone who has been around the world, although he calls New York home, and who has followed many spiritual practices from the Siddha Yoga teachings of Gurumayi to more recent experiences with channeling through mediums and is a follower of Mother Meera, who he visits often in Balduinstein, Germany. He is also something of a legend professionally, having blazed his own trail much of the time. Contrary to the idea, cherished by novices and outsiders, that an artist must convince a prepotent owner of means to accept his work, Slonem successfully made his way for many years without being represented by a single, major, art dealer. Instead, he was able to secure a steady stream of gallery and museum exhibitions throughout the world, receiving abundant critical and journalistic attention for his work and lifestyle. It was because of his self-generated career and market that Slonem was ultimately approached by Marlborough Gallery, who has now represented Slonem since 1997.

Slonem’s upbringing may have contributed to his self-reliant, peripatetic nature as an adult. His father was an Navy Captain, stationed in Kittery, Maine, when Slonem was born. From Maine, the family moved to California, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Virginia, Washington State, and Hawaii, where he encountered a variety of tropical flora and fauna that would inspire him in later years. In high school, Slonem spent six months as an exchange student in Nicaragua, where he often visited the jungle to observe butterflies and birds. While a junior at Vanderbilt University, Slonem was offered an opportunity to spend the year at the University of the Americas in Cholula, Mexico, (he later transferred to Tulane, where he received a BA in Painting and Art History in 1972. He began to visit New York in 1972, without knowing it would become the city in which he would eventually settle. An important artistic stage for the young artist was the summer of 1972, which he spent at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, in Maine, having found about the school from painters Emery Clark and Mary Burton Wheeler. It was at Skowhegan that Slonem first had contact with artists who were significant figures in the New York art world; that summer, he met Richard Estes, Alex Katz, Alice Neel, Louise Nevelson, and Philip Pearlstein, not to mention Bette Davis, who was a friend of the school’s founder, Willard Cummings. In the fall, after receiving a scholarship to the Banff School of Fine Arts in Alberta, Canada, and not liking it, Slonem resolved to move to New York, where he has been based ever since. His first project, once there, involved using holy cards from Nicaragua and Pre-Columbian sculptures from Mexico and Morocco as subject matter for paintings.

Two early bodies of work brought him attention: a series of paintings based on images of particular saints and one of paintings of gold Incan artifacts, whose images Slonem took from photographs. His work found a context in group exhibitions, mainly in the East Village, with the titles “Exotica,” “Stigmata,” “Precious” (at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery), and “Revelations.” In 1983, The Metropolitan Museum of Art bought a Slonem painting of Saint Martin de Porres from a group show titled “Saints” at the Harm Bouckaert Gallery.

The saints that have appeared in Slonem’s paintings are Saint Niño de Atocha (13th Century), Saint Martin de Porres (1579-1639), Saint Rose of Lima (1586-1617), Kateri Tekawitha (1656-1680), and Dr. Gregorio Hernandez (1864-1919). Saint Niño de Atocha appeared in Atocha when Spain was under attack by the Moors. Strict prohibitions had been placed upon captured Spanish soliders; only children could bring food to their relatives. El Niño de Atocha, dressed as a pilgrim, began giving wood and water to the prisoners. He also performed miracles well beyond the region of Atocha, including guiding refugees to the safest roads. He always dressed in a hat and ornate cloak and held a basket of roses or food in one hand and a pilgrim’s staff in the other. Saint Martin de Porres was a Peruvian lay Dominican brother, born in Lima, the son of a Spanish soldier and a black Panamanian freedwoman. He devoted himself to the sick, built an orphanage, and founded several nurseries. He was known for bilocation, levitation, miraculous knowledge, instantaneous cures and an ability to communicate with animals. One of his symbols was the grouping of a dog, a cat, and a mouse, who ate together without fighting. St. Martin de Porres is often depicted with a broom, since he thought all work, even sweeping a floor, to be sacred. He is the patron saint of African-Americans, bi-racial people, hairdressers, hotel-keepers, mulattoes, and race relations. He was canonized in 1962. Saint Rose of Lima, a colleague of Saint Martin’s, was also born in Lima and became a Dominican tertiary and mystic, later canonized as a saint of the New World, patron of South America and the Philippines. She was known for her life of austerity and devotion. Kateri, also known as Lily of the Mohawks, was the daughter of a Christian Algonquin woman, captured by the Iroquois and married to a non-Christian Mohawk chief. She converted to Christianity in 1676 and was known as a miracle worker. She was the first Native American proposed for sainthood and was beatified in 1980. She is the patron of environmentalists and exiles. Dr. Gregorio Hernandez was a well-educated Venezuelan doctor, who traveled to France to study bacteriology and pathology. In 1891, he became Professor of Medicine at the Central University of Venezuela. He wrote many scientific works and also a book on philosophy. He often treated the poor for free. After his death, his fame as a healer and spiritual assistant to doctors grew. He has been beatified and, when canonized, will become patron saint of Venezuela and of medical students and doctors. He is usually depicted wearing a suit and hat. While Slonem’s early paintings of saints triggered an empathic response in viewers and brought him into a cultural context in the art of his time, the paintings are often static, the figures stiffly painted. The most intriguing thing about them is how the saints often seem almost devoured by lush landscapes around them. This lushness was a precursor of a type of art Slonem would one day create, that perhaps he wanted to create even then, but it would take several trips to India and changes in perspective before he could arrive at that artistic place.

Travels and homes have been significant inspirations for Slonem. The saint paintings came out of trips to Central America. A later series of paintings involving rope that Slonem hung in his bird cages derived from several trips to Haiti. A major change occurred in Slonem’s life and work when he began traveling to India in the mid-1980s. He did a painting titled Bombay Zoo, 1989, which came from his experience of seeing birds in large cages in that city. Also while in India, Slonem was asked to help design a space for birds at an ashram. Back in New York, he painted his own birds: Piculs, Chattering Lorries, Toucans, Lady Gouldian Finches, Parrots, Java Ricebirds. He has also owned a Kookaburra, a Hammercock, and a Peacock, as well as several monkeys and cats. The ritual of feeding and caring for animals parallels Slonem’s daily ritual of preparing and painting canvases. Every morning, Slonem chops up large bowls of fruit, tofu, chickpeas, corn, mealworms and defrosted mice. While feeding his birds and cleaning their cages, he collects their molted feathers, accumulating them for large-scale installations, inspired by Meret Oppenheim’s famous fur-lined tea cup and Hawaiian king’s capes, made by collecting moulted feathers of the Mau Mau bird, a process that can take 300 years.

The variety of tropical bird species in Slonem’s work has led to a marvelous diversity of formats in which he has painted them, from the miniature to the gargantuan. He began living with birds in the early 1980s, building a 40-foot long cage to house them in his first loft, which he still maintains, on the corner of Houston Street and the Bowery. At a certain point, he realized he had been living with them but had not painted them. Thus began a shift in Slonem’s work that put him on the path he still travels today. Unlike his gold paintings, his paintings of saints, and his early paintings of animals in jungles, the bird paintings were done wet into wet and took spatial compression and ambiguity to new extremes. The early paintings were done over longer periods of time, allowing Slonem to re-consider their complex compositions, but forcing him to work on dried or drying paint, thus limiting the mobility of his brush and color interactions.

With the bird paintings, Slonem was able to work rapidly, arriving at finished paintings with a fresh pictorial framework intact. He tends to work on several pieces simultaneously, but each one takes only a day or two to be completed. He usually starts by choosing a solid color — a bright red or green, for example — to paint on an entire canvas, or sometimes, different solids on different parts of the canvas. He then begins to layer imagery over the solid color. He paints quickly, filling the canvas intuitively, as opposed to composing his pieces in advance. The birds as subjects have many connotations and cultural references, some of which are purely decorative. The Gold paintings had compressed spaces, as they were, in essence, close-up views of artifacts blown-up to New York School painting size. The Bird paintings, whether large or small, often use a murky, suggestive, idea of space inherited more from painters like Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still. Wanting to take into account the relationships of birds and humans, acutely aware that many species have become extinct and many others are in danger, Slonem decided to include the cages as well the birds in his paintings. Liking to strike as many variations as possible of a visual idea, he did paintings in which he painted cage bars only in back of the birds, only in front of the birds, or in back and in front. The cages, despite their strong connotative impact, also function largely as formal and decorative elements. Space is still quite compacted, with only flashes of light visible from beyond the cages. A little later, Slonem began scratching marks to represent the cage bars, using the handle of his brush, instead of painting them. This different technical effect was a central element in a large, signature, body of work for Slonem. The scratched hatch-marks enhance a visual unity that already exists in the works. They function as a way of finishing the pieces, giving them an impression like that of an overall light. Simultaneously, the hatch marks are aggressively formal and surreptitiously link Slonem’s enterprise to a history of Minimal art from the 1960s and ‘70s based on use of the grid.

Birds can conjure a range of symbolism, and almost every culture involves depictions of them. For me, birds bring to mind Giotto’s depcition of St. Francis preaching to the birds in Assisi, the whistling bird animation in Mary Poppins, and Pasolini’s comic transformation of St. Francis via the amazing facial contortions of the actor Totó in the film Uccelacci e Uccellini (Hawks and Sparrows). Another body of work that comes to mind is found in the frescoes painted on walls of villas near Naples during the 1st century A.D. These frescoes, with depictions of architecture, and architectural fantasy, as well as sexually explicit images and mythological references, also contain work that is smaller scale and deals with the facts of daily life — particularly food and its tools of preparation and consumption. Within this group, one finds many depictions of birds. There is a fresco that features a delicate, precise picture of a kingfisher presiding in the midst of a shallow space over an array over sea food — squid, lobster, clams — and a fishing trident. The bird is included as an example of a fisher par excellence. This is different from how Slonem would use a bird image, in that it relates directly to human consumption, whereas Slonem’s concerns are more spiritual, but the importance of the subject in this composition and the care with which it was painted make it a worthy precedent. There are also Neapolitan depictions of partridges, geese, warblers, flycatchers, parrots, roosters, ducks, peacocks and the Purple Swamphen, of which Pliny the Elder wrote that they were kept as pets by the rich and were the only birds that Romans did not eat.

There is something about Slonem’s main manner of painting, of working to fill space without hierarchical subject in a highly skilled manner that has long reminded me of Islamic art. While Islam is not a faith that Slonem has pursued in his personal life, I find a proximity in his work to certain Islamic models. Islamic art has its core the glorification of Allah, and there is a philosophical core that Slonem’s repeating patterns approach.

The most fundamental pattern [in Islamic art] is the creation of the infinite pattern… The infinite continuation of a given pattern, whether abstract, semi-abstract or even partly figurative, is…the expression of a profound belief in the eternity of all true being… In making visible only part of a pattern that exists in its complete form only in infinity, the Islamic artist relates the static, limited, seemingly definite object to infinity itself… One of the most fundamental principles of the Islamic style… is the dissolution of matter. The idea of transformation…is of the utmost importance.”

Ernst J. Grube, The World Of Islam (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1966), p. 11)

When the Umayyads, who emerged as leaders of Islam after the death of Muhammad in 661 A.D., moved the capital of Islam from Medina to Damscus, Arab culture came into contact with Greco-Roman culture, provoking one of many moments of fusion in the arts, with qualities not unlike those among which Slonem began to work.

While engaged with the birds, Slonem began other series — infinite, end-to-end, monkey heads he calls Guardians, rabbits, chandeliers, butterflies, flower and plant compositions. Each series brings Slonem into different iconographic realms, yet the technique stayed very much the same. In the 1990s, he began a body of work based on Rudolph Valentino and his circle, and a body of mysterious works, usually with a dull gold tonality, from which glimmer heads and vegetation. In addition to oils on canvas, Slonem has worked extensively in watercolors, and has made prints and sculptures.

Partially, Slonem’s approach to art can be seen as one of wanting to combine life details and aesthetic techniques from cultures at odds with the dominant models found in first world cultures into formats inherited from the later periods of high Modernism. In other words, there is, in Slonem and his work, a fascinating bi-polarity, or multivalence. For all the spiritual practices he has undergone throughout the years, Slonem lives very much in the world of New York’s high-consumption fast lane. Likewise, his interest in Rudolph Valentino and his circle might be different from what one first imagines.

In the mid-1990s, Slonem stopped seeing Gurumayi and began seeing an array of psychics. One of the results of his experiences with channeling has been a focus on the world surrounding Rudolph Valentino. To an outside observer, who may not have the same experience or interest in channeling as Slonem, the main fact of interest must be the significance of these figures as images. In the 1970s, Valentino was still thought of as a huge star with a star image, and one would find his picture in poster shops, alongside those of Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and James Dean. Things may have changed since then; Valentino may have receded into a more distant past; but for those interested in the history of cinema and the early years of the star system, the teens and the twenties are a period of endless fascination.

The paintings of Valentino’s world have given Slonem an avenue to re-figure the human form, something in which he invested energy early on in the saint paintings. What do the Valentino paintings say in comparison to the Saint paintings? Whereas the early works put Slonem into a world interested in such topics as “Exotica,” “Stigmata,” “Precious,” and “Revelations” (all these were titles of group exhibitions Slonem appeared in), indicating timely explorations of non-logical, non-scientific, world views, the recent paintings have more to do with the representation of glamour, thus representing another important side of Slonem, his life as a participant in New York City’s high culture and night life. Valentino has long been a particularly gay symbol of sexual power. His colleague, Alla Nazimova, worked with Stanislavsky in Moscow, knocked them out on stage in New York as Hedda Gabbler, and went on to be the highest-paid female actor in Hollywood before the arrival of Garbo. She was infamously independent, eventually starting her own production company, and lived an openly bisexual life in her garden of Alla mansion. Two of Nazimova’s girlfriends ended up married to Valentino. In my opinion, it is this world of unrepressed emotions and high style that Slonem references in his Valentino paintings. One may ask if he has devised a painterly style that corresponds to this subject, in the way that he devised a painterly style to correspond to his involvement with the birds. Slonem has used photographs or other found images as source material, from which he paints, in the Gold paintings, the Saint paintings, some Bird paintings, and in the Valentino paintings. Aside from several Valentino works, in which he attempted to move into large scale multiple figure compositions, Slonem has not really changed his technique since the post-India wet-on-wet transformation. One wonders whether the Valentino world deserves some new technical investigation to embody it.

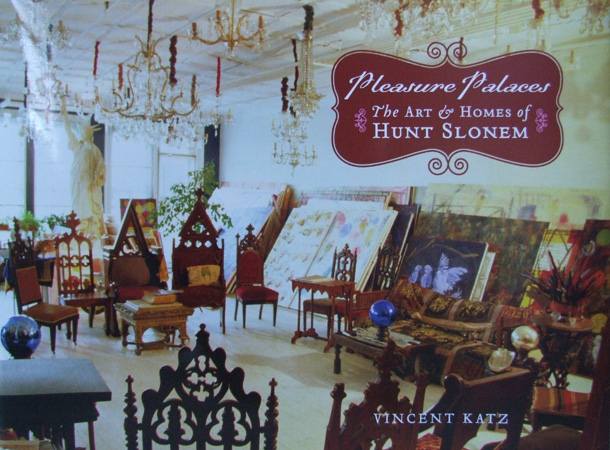

The story of Slonem’s homes forms yet another layer in his life — parallel to his travels, his spiritual involvements, and to his prolific career in painting. His longest-standing situation in New York City, which he moved into in 1975 is a 2,800 square foot loft on the second floor of an 1860 brick building on the corner of Houston Street and the Bowery. Ever more central, this was once a distant outpost, bordering one of the widest and wildest intersections in Manhattan. It was there I first met Slonem, encountered his birds, in and out of their cages, and found the intriguing way his work was done in a space that also served as a living room with its circle of Neo-Gothic chairs. What struck me was how the work was constant and how each new painting took its place at the front of a stack of its predecessors. There is always a struggle for space for New York’s artists, and Slonem seemed to circumvent it. I questioned the safety of this piling practice for his works — some were found with stacks of paintings weighing into their surfaces or with their paint stuck to another painting. His attitude was refreshingly unprecious. It was as though the works had been pushed out of the nest and needed now to fend for themselves. Slonem still sleeps on Houston Street when in New York.

20 years after moving into Houston Street, space had become an urgent issue for the prolific painter and collector. Serendipity struck when he was offered a 10,000 square feet space in the Starett-Lehigh Building on West 26th Street, facing the Hudson River. This building, built in 1929 and famous for the Art Deco curved corners on its massive exterior, was the crème de la crème of industrial space. Its enormous elevators easily bring huge trucks up to its floors, where there is ample parking; and that’s just the infrastructure. Slonem’s space was like a railroad apartment on acid. One walked down a long corridor, with room after room opening off to the left. Each room was a different color and had a different meditative feel: the first room was the office, whose black leather sofa invited both inspirations and daydreams; there followed the pink room, its color taken from a packet of Sweet’N’Low; a bedroom hung salon-style with small Slonem’s in antique frames; and the green meditation room, with its papyrus pool and candle stand, replete with devotional tokens. Finally, at the end of the hall, after passing a modest kitchen, restroom stalls, and Hunt’s enormous dining table, surrounded by more Neo-Gothic furniture, one arrived at the principal space, large, open, with windows on its South and West sides; the enormous black sofa that had once resided in Andy Warhol’s factory looked in perfect scale here, neither too large nor dwarfed. Through a forest of plants and birds, one arrived at the painting area, and it was there and then that Hunt clicked into a painting rhythm that has not stopped until this day. The 26th Street space was fully functional, with storage racks and enough space for paintings at all different stages. It was a space with a “good-omen” feel to it (a phrase Willem de Kooning once used to describe the poet Frank O’Hara). I felt so comfortable there, I asked Hunt if I could write a poem there, which of course he agreed to. It ended up being the long poem, “Painted Life.” In that abstract poem, one can find myriad details of Hunt’s space, the music he listened to, the light and the view of the river and Chelsea.

I have used the past tense when describing 26th Street, as Slonem was forced to leave it in 2003. He takes a philosophical outlook to these changes, believing that everything has its time, and unbelievably, he seems always to find a new place more spectacular, or at least larger, than the one he has left. In 2003, Slonem moved his studio to another 1920s structure, this one on10th Street, again facing the Hudson, and this time with an astounding 50,000 square feet or office space with acoustical tile ceilings and 89 rooms. These rooms were filled with broken office furniture when Slonem moved in, but he soon transformed them, painting them vivid hues of green, orange and yellow, transferring the pink room, and creating rooms for drying paintings, rooms for offices, room for black and white paintings, a butterfly room, a shell room, a Ganesh shrine, a St. Francis shrine, a Dr. Gregorio Hernandez room, a Mother Mira meditation room, a monkey room, a red portrait room, a pink room, a changing room, a black tie room, a thank-you-note room, an Archangel Michael room, a bunny room, a brown room. And oh, yes, there is a large enough space for Slonem’s dining table and his painting apparatus.

In 2001, Slonem felt the need to expand beyond Manhattan’s confines and purchased Cordt’s Mansion in Kingston, New York, which formerly belonged to Matilda & Florence Cordt. Built in 1873, the house was once Kingston’s principal mansion, boasting 12,000 square feet, including a carriage house and two caretakers’ residences. Slonem has done paintings based on the landscape around the grounds and its flora and fauna. He has done a series of Morning Glory paintings there as well. Slonem speaks of an “upstate” sensibility, citing Frederic Church’s neo-Persian mansion, Olana; both homes, and many others in the area, are decorated with yucca plants, popular in the Victorian era, and hollyhocks.

Traveling ever further, Slonem’s attachment to New Orleans and Louisiana in general has inspired him in recent years to purchase two large former plantation homes. The first is Albania on the Bayou Teche in St. Mary Parish, about two hours’ drive northwest of New Orleans; Slonem bought Albania in 2004. Built in 1842 with 10,000 square feet to its interior and an additional 5,000 square feet of porches, Albania has a typical layout of many plantation mansions in that area, an area that generated incredible wealth between 1800 and the Civil War, mainly in the production of sugar. The houses fronted onto the Bayou, the water entrance being as important as the land entrance on the other side. There were dovecotes, significantly for Slonem, separate kitchen and other out buildings. The main residential building is a masterpiece of period architecture, with its harmonious bays and simple square columns. Charles François Grevemberg finished building the house in 1842. After his death, his widow ran the plantation. In 1860, Mrs. Grevemberg owned 201 slaves, 1,507 acres of improved land, and 5,000 acres of unimproved land. The value of the farm was $200,000, the machinery $30,000, and the livestock $25,000. Albania follows the typical plan of a Louisiana plantation, as laid out by Clarence John Laughlin:

…near the river would be the main house (usually led up to by a great avenue of oaks); its pillars for the most part entirely surrounding the house; flanking it to either side were two garçonnières much smaller in size (originally, these were for the sons of a family and his friends; later, they were simply guest houses); behind the main house were normally two more structures — the plantation overseer’s office, and the plantation kitchen (kept separated, in most cases, from the main house because of the danger of fire); somewhat further back were often dovecotes or pigeon houses; then the twin long lines of the slave cabins (the earlier ones of brick, the later of white-washed wood); succeeding these, the cane or cotton fields, and finally, either the cotton gin or the sugar mill.

In meditating on the effect the plantation has on him, Slonem says, “It has that wonderful smell of Louisiana, of mildew, stale cigarettes, and orange blossoms.” There have been only three owners since Albania was built in 1837. To complement the 150 year old Live Oak trees, Slonem has planted Australian fern trees and a Satsuma orange grove that he is doing paintings from. Similarly to the description above, Albania has eight out buildings, including chicken coops, former slave quarters, a summer kitchen, and two dovecotes. He has been doing paintings of Albania in New York, from memory. “That’s how deep an impression Albania Plantation makes on me every time I’m there — the Spanish moss, the camellias, the white ginger, cottonmouths and water moccasins, the bobcats in the yard.”

In 2005, Slonem supplemented Albania with the purchase of yet another plantation home — Lakeside, built in 1835 and composed of16,000 square feet. As Slonem puts it, “The thing about Louisiana that’s influenced my work a lot is the Spanish moss and the Camellias and a flower called the Shrimp Plant, which is native to Louisiana and grows all over the front of the property. There’s always something in bloom there. I have a record of the day the 150-year-old Live Oaks were planted. I’m putting in five or six new ones every year. They harbor everything, from snakes to owls to bromelias. It’s this whole Tree of Life thing. Cypress trees, I just found out, have a life expectancy of 1,000 years.”

Hunt Slonem has written a poem which brings together in concise form many of the ideas and images that have been with him throughout his life. Pele is the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes and fire. As a child on Hawaii, Slonem used to find tear-shaped formations in green Obsidian glass, created when a volcano erupts. All these times and places, sights and smells come together to form a particular contemporary consciousness.

Staterooms on destroyers

Ocean liners to Hawaii

Pele’s Tears and black sand beaches

Vanda orchids

White catelayas

Plumeria and picaque leis

Champas glows India

White Ginger

Feilber roses in Guatemala

Orange shirts to work in

What ultimately affects us, when viewing an artist’s work, is the coherence of the technique with their imagery; then there is the question of how the particular imagery resonates with the viewer. Take the case of Andy Warhol: his mechanical approach to image-making, with the corollary that anyone could make his paintings, was perfectly suited to the found newspaper and tabloid imagery of disasters and stars from popular culture. In addition, his images had a terrific resonance for the public of his time and for long after his death. In the case of Hunt Slonem, his fast, slashing, improvisatory technique coheres with his patterned, brightly-colored images of exotic animals, things, and people. His technique, supported by his daily painting practice, has improved considerably from his early Gold paintings. One wonders now if he will branch into some other category of work, that will take his technique into even more rarefied areas. In the meantime, we are left with his imagery to contemplate and enjoy.

|