home | books | poetry | plays | translations | online | criticism | video | collaboration | press | calendar | bio

| Art Books and Catalogues | Curatorial | Poetry | Translation |

|

|||

|

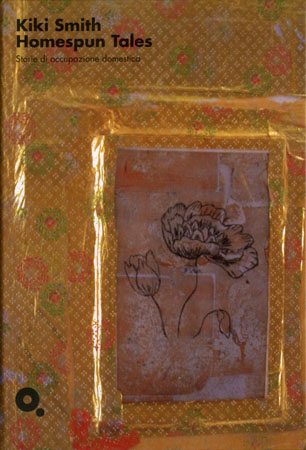

Kiki Smith: Homespun Tales, 2005, Fondazione Querini Stampalia, Venice, Italy |

|||

|

CHIARA OSCURA: A knock on the door. Somber, mystified footsteps trailing away. The same cold soup as always. Damn! It is left for hours while the work continues, then devoured greedily in competing gulps, then the plate is licked and scoured with the crust of bread provided. And the work continues. It is the compilation of the archive of documents of one of the most significant Venetian families of the past four centuries. And so there is no time for food, for repast, even for contemplation, let alone for poetry. Yet, poetry does get written, from time to time, on a rainy balustrade, when the smell of urine rises to the rafters. Poetry along the lines of: “You can portray the maiden, noble, fair,/charming of face and stately in her mien…” What should come before or after that? How to think of looking at, much less portraying a maiden — whether noble or ignoble. Would her nobility or ignobility be visible in her face, apart from clothing, hair and accoutrements of position? Where would one start, and where finish, in an attempt to convey coherence in that social picture? Or should coherence be fractured? Must it be? Must we simply portray the varied figments that attract our attention and drive us close to insanity in the closing minutes of the day, when no one is left nearby, and still the work continues? A blasted knocking from below, a hammering. How can anyone think? Let’s see… The documentation of purchases and gifts. The acquisitions, or better, the coming to be part of a family’s patrimony, of works by Mantegna (though some insist it is Bellini), Strozzi, Palma, Tiepolo, Longhi and Bella. Then there is the library of over 3,000 volumes, but that is looked after by a crew of bibliophiles, much too cold-blooded to deal with the passions of the depicted image. Maps, manuscripts… Then there is the fantastic collection of Sèvres! Alvise Querini Stampalia bought it in Paris in 1795, when he was finishing up his ambassadorship there. It contains 96 plates, 36 soup bowls, 12 fruit dishes, 16 compôtiers, 28 ice cream glasses, four saucers for them, 2 sugar bowls, and much else. The remarkable figurines of The Triumph of Beauty and The Lover Discovered. It is my job to ascertain the existence or non-existence of any and all paperwork for each purchase or gift. This imposing house rose to prominence in the 15th century and continues near the end of our own century, the 18th after the birth of Christ, and will continue for another 18 more, as far as can be seen, thanks to the good foresight of our city’s founders. I have to smile when I think of the name they gave our Republic, “the Serenissima.” Of course, there is in that name all the poetry one may find in the modeling, the scale, of Longhi’s paintings, for example, how he demonstrates an astonishing variety of social positions within a sophisticated painting style that appeals to its primary audience as being totally contemporary. Even our Sèvres pieces, on their more intimate scale (though not so much smaller than a Longhi painting, the world they imply is one of plates and silverware, whereas Longhi’s is one of walks and boat outings) express a contemporaneity of concept that will remain fresh through centuries’ vagaries. But the Serenissma was anything but Serene for those it opposed. For them, it was the Ferocissima! There is expression of that in our art and literature, as in Gabriel Bella’s painting of The Battle With Clubs, but it is couched in the cultural terms that praise violence in the name of valor as a necessary underpinning to the Republic. The Republic has endured for a thousand years, and who’s to say it won’t endure for a thousand more? Venice still lives by the sea; her coffers are weighty; men of importance still pronounce somberly on matters only they have the ability to speak of. The Querini Stampalia form an important element of the city’s functioning leaders. The arts continue to be extravagant and world-class. I must really go down and see what that infernal racket is all about. I cannot concentrate one iota on my research — it’s all up in smoke. I haven’t exited my rooms in some time. How much time? Weeks? Months? Everything is made — I wouldn’t say “easy” for me — but made so that I may continue my work efficiently. New elements are continually brought to me, and I continue to process them. Now, for the first time in weeks or months, I descend from my scholar’s garret. The hammering grows closer, more metallic. It is echoing as though someone is banging a huge gong inside my hideaway. I go down a long dark hallway. At the end, an enormous door stands ajar. I hear laughter. My heart beats faster. I pass the threshold, gliding at top speed.. What I see gives me a shock from which it takes seconds to recover. There, in bright light, sitting on the floor, is a group of the oddest figures I have ever laid eyes upon. Slightly disheveled yet possessed of a graceful innocence, they sit in a circle smoking and talking in low tones. They are like pilgrims or devotees of some strange cult, their spirits extended in the accomplishment of a task, at first undertaken for the benefit of humanity (and oneself), now subsumed into a practice ever more distinct as its own reason for existence. Stealthily, I creep closer, remaining in the shadows, close to the pool of light illuminating these speaking seated figures dressed in white, as plumes of smoke rise from their conversation. One is in the center, and she is speaking now to the others, explaining the motivations for their current acts of self-sacrifice. Because of the glow surrounding her, I will call her Chiara. This is what I hear. “…You know, house-museums, or museums with some other historical information in them. Not just contemporary art spaces. I like spaces that have histories and are interfered with and have interfered histories. They have this beautiful garden that Carlo Scarpa redesigned, and they have a library. They have a storey which is their house-museum storey, which holds their possessions. So I thought: I'll make the exhibition space back into a house — a mirror house-museum. And so everything I made for the show, I tried to make in relationship to what they have in their collection. They have lots of mirrors, so I made mirrors; they have paintings of Sibyls, so I made paintings of Sibyls. But I made a fractured version, using my fantasies of colonial American homes, together with an idea of transient squatters living in palaces. There is a large formal entrance hall with a lot of little rooms off it. I was thinking about SROs, and transient boarding houses, and ways women live. I took women from the Pietro Longhi paintings in the collection, and first I conceived other stories — alternative stories — of what those women were doing. Then I made little ceramic porcelains in relation to them. I tried to think about other women, people I knew when I was a child, or myself, sometimes, living in transient hotel spaces. They have this enormous Sèvres collection, where they have the dessert service, and they have figurines all over the walls. I wanted to make things in relation to those. I'm not making anything new, but I'm not really making artifacts. I’m in some weird other space, in between, that involves learning through doing. The little group leans back their heads and laughs deeply in the silent Venetian night. I creep away, stunned, back to my room, my papers, endless notes, the candle guttering in its plate. I hear the bells of Santa Maria Formosa and several other nearby churches blending in their tolling of minor thirds. How appropriate, I think, as I open my shutters, that the Maria here should be Beautiful, since Beauty is being made and examined — not preserved, but made to be living here. How can this person from some other age understand exactly what I, in my garret, am experiencing? How can she know what we are all living through? She must be an ageless spirit. As I see the dawn’s light beginning to color my fantastic city, I think: She shines darkly, illuminating us. And now I can back to work. [Author’s Note: the long quotation in the second half of this piece is from an interview with Kiki Smith, conducted by the author on 15 April 2005.] [Requested reproductions: |

|||