|

Juan Gomez : A Painter Of Differences

by Vincent Katz

Juan Gomez does not sit still. As a man, he left his country and found a new home, where he can practice his devotion to the art of painting. As a painter, his work has embodied multiplicities many artists never achieve. The most obvious one, the one a reader of supposed meanings of artworks, as opposed to an appreciator of art languages, would notice, is the alternation between abstraction and figuration, but this is only part of the story. More importantly, he has moved from a language that was spontaneous and squalling to one that involves extreme calculation and equilibrium.

Born in Bogota, Colombia, Gomez grew up in a family that valued the arts. His parents took him to the Museo del Oro, which holds whatever pre-Columbian gold work was not pillaged by the Spanish, and his grandfather was an architect who had an active social life. “We had a summer place where his friends would go, musicians and artists,” Gomez remembers. “I saw painters there. I remember someone painting in the house, and one of my aunts painted a mural there. My grandfather’s sister makes pottery. She had a workshop in the city, where we would go, and she would let us play with the materials.”

After a disappointing stint trying to study commercial art at university, Gomez decided to move to the States. “I wanted to get away, leave everything,” he remembers. “I was fed up with the situation in my country, which is not very receptive to anything that is different.” Eventually settling in New York, he studied first at the Art Students League and later at the School of Visual Arts. Among his instructors were Jan Avigkos, Caroll Dunham, Lucio Pozzi and Barry Schwabsky, but the one who had the greatest impact on Gomez was Haim Stainbach. Stainbach told Gomez that he was in a medium with tradition and history. “’Your options are mapped out for you,’” Gomez remembers Stainbach saying. “I was painting abstract, and he sent me to look at Soulages, which I didn’t like at all. He told me to find my peers. For him, painting was a hard road to choose for an artist — he was very critical of painting and of my doing painting. He never told me he liked my work, but he challenged me.”

In the late 1990s, Gomez was making erotic drawings, but his paintings of the same time were abstract. “The drawings were like journals. I was not trying to produce finished work. When I approached the painting, I remember thinking, ‘These are abstract, because my purpose is very abstract.’ I remember feeling as though someone had dropped me in the middle of China, a place where no one understood me, I didn’t understand anyone, so that’s what I could express, without words, without figures. Those were the only parameters I gave the paintings. I didn’t play with concepts or the history of painting.”

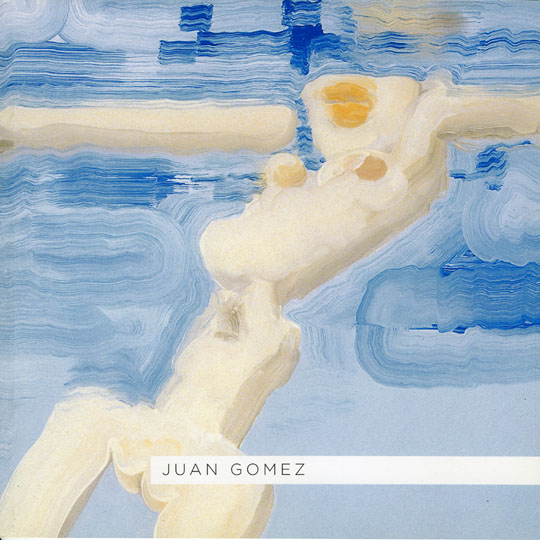

The nudes are a major breakthrough for Gomez. Having worked in increasingly astute abstract techniques — first in jagged flurries of cross-fire strokes, then in dense fields animated by winding paths scraped into the paint — Gomez achieved the ultimate synthesis when he brought the nude female figure into these wavering, linear fields that have a vaguely pre-Colombian air. The figures seem oddly contemporary. They all depict the same woman, whose only hair is on her head and who is composed of scrubbed, elongated, parts that fit together, or fall apart, like an erotic construction set.

The imagery seems to speak of breakdowns, which could be the dislocation felt during or after sex, the dislocation of being in strange place (she seems in fact to be in no particular place), or it could be simply the dislocation of existence itself, of trying to be a human being in a world that is frequently inhumane. These questions of humanism bring to mind a precursor to these abruptly mutated females, namely the nudes of Picasso. As with the Catalonian master, the female form in Gomez’ paintings is broken into parts, yet one does not necessarily take this as objectification. The figures in Gomez’ paintings are not made to seem available, as are even the most tortured of Picasso’s figures.

Juan Gomez’ work, whether in oils or in watercolor, clearly signals his desire to place himself within the tradition of western art. The coloration of the watercolors brings to mind old master drawings, as does Gomez’ facility with form. Other artists come to mind — Guston for the bluntness of his figures and Dunham for the playful perversity of his images. One is taken, over all, with the materiality of Gomez’ work and comes away from it wondering if, despite the titillation of the imagery, the main attraction is of someone who is really involved with the mediums of paint, who is not only willing to work through that, but who can provide rich textures and shocking contours, for which lovers of technique will be grateful.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Blind Hymn

The mongers move together in a circle, circulating wares, comparing, noting

But nothing is very different, it is rotten, there is a dull light pushing integers

Across a vast area, in which several indistinct children play tentatively with a

Ball, no dinner bell is rung, no keyboard clatters, just the sound of boat horns

Insistent in the fog that brings every day to a raw finish, a bleating or purpose

December 15, 2005

São Paulo

|