home | books | poetry | plays | translations | online | criticism | video | collaboration | press | calendar | bio

| Art Books and Catalogues | Curatorial | Poetry | Translation |

|

|||

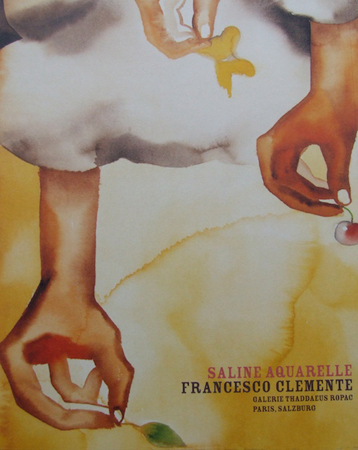

| Francesco Clemente: Saline Aquarelle, 2004, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg, Austria | |||

|

Interview with Francesco Clemente by Vincent Katz Vincent Katz: When you start on a series, do you work spontaneously, or do you have imagery in mind? Francesco Clemente: The images present themselves very quickly, in a rushed, hectic, vivid, urgent way, so usually the very raw ink drawings I just take down very quickly to remember what I see, and then that's sort of like in music, a score, that is very quick. VK: So for this series of paintings, for example, that's around us, they all come from smaller studies? FC: Drawings, yes. But I wouldn't call them studies, because they have nothing to do with the form that then the work takes. They've really to do with the reason why the work comes into an existence, which is this constellation of images that wants to come into existence. VK: When you translate it, or when it moves from a small version to the painting, is there a transformation? FC: Yes, there isn't a smaller version of the work. I could write down the description of what the image is going to be about. I happen to draw it, because it's faster than writing. And then, of course, according to which medium I'm using, my relation with this image changes. If it is a pastel, it's a more intimate and again fast process, where I'm always within that emotion. When it comes to painting, there is a fragmentation and also an extension in time of the emotion. I'm a little more impassive maybe, a little more distant. VK: How quickly do you work on paintings, in general? FC: Slow. Pretty slow. VK: And those outlines are done in, it looks like, some kind of a stick? FC: Usually with paintings, I don't make preparatory drawing. In the case of thinner painted works, which I've done in the last years, I did make a drawing using paint, and I would let some of the pentimenti show through. In the case of these paintings, which are painted in a thicker impasto, it's the first time. I feel I can have more concentration on the way the paint then sits, if I don't have to bother about the outlines. VK: Ted Berrigan wrote a poem called "Cranston Near The City Line," which contains the lines, "I never told anyone what I knew. Which was that it wasn't/for anyone else what it was for me." Was there a moment when you had that realization, that you felt -- FC: The calling? VK: that you were an artist? FC: I guess I only knew what I could not be, what I did not want to be. I did not want to make a deal. I did not want to play. VK: But did you have any of the feeling that he alludes to, a kind of separation from society, or from that society one finds oneself in early on? FC: Definitely. Definitely, yes. But there is a large slice of human knowledge which is about that. It's about the feeling to know more than the actual knowing. It's a dangerous knowledge, of course. It can generate terrible misunderstandings. Because it involves also emotions. VK: You once said that painting is the last oral tradition, and I found that really to be true. It does get passed on by people talking, a lot of the time. You also said you were preserving a feminine spirit of neolithic times. What do you feel that oral culture allows that perhaps the academic or written culture sterilized against? FC: Well, how can one say this lightly? We live in the civilization of the book. So, to turn your back to the book is really to jump into nowhere, to jump into what is specific of the poet, of the painter, of the musician, to jump into territory where nobody ever goes. And I think I was only stating a very matter of fact process, which is that when you become a painter, there is another painter who authorizes you to do what you do, and by doing certain works all of sudden you can authorize other people to do those kind of things. That to become a painter or a composer or a poet it's not enough to go to school. You have to admire somebody, you have to be drawn emotionally, with all your heart, all your body, all your mind, to someone who's come before you who makes you feel that, yeah, you want to talk to that particular person. And to talk to them, you have to be like them, and to be like them, you have to see what they see. That's an oral tradition, where knowledge is not an object, which both of us look at from a distance. Knowledge is actually a field between us, that we create between us. It's not something objective or external to us, it's inside us. And so it's also delusion, it's mystification. There is all of that edge to it. It's intangible, it's ridiculous. VK: I guess there's also an element of trial and error, when you have to physically or actively enter into it. FC: It's weak, also, it's very weak. VK: In what way? FC: In every possible way. I mean, compared to scientific knowledge, it's weak. It's a very weak noise, compared to very loud noises that science and industrial ways to communicate produce. But the fact that it's weak doesn't mean that it doesn't exist. Weak things exist, and they're lovely. VK: Now there is a new generation of artists coming; do you see work that interests you, and do you feel connections to any younger artists in a different way than you may have felt to your contemporaries? FC: I had a great relation with the people who came immediately after my generation -- Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, who were good friends and very intense inspiration and so on. The affinity I felt for them was that both of them were drawing into the world of painting and art from other worlds. They were drawing information, energies, from something that had nothing to do with painting and the arts, the urgency of that kind. I feel less affinity with people who are meditating and reflecting on formal questions relating to the arts and to paintings and to the contexts of paintings. I have an interest for it, and I'm always amused by it, but I don't feel moved by it. Which is a little bit where right now seems to be -- the new figures are more drawn to those questions, again, like the people before. Almost back to the people before, in the 1970s. VK: You have mentioned feeling an affinity to artists at different times, and in a way, it's difficult to place yourself in one specific moment. Bergman has said he can close his eyes and completely visualize his grandmother's house, and he has a strange, collapsing sense of time. Do you feel that sometimes you're not actually living in New York? FC: Well, one draws a line between first-hand and second-hand, you know? The context we live in is the proliferation of second-hand, of mediation, of everything that gets to you from somebody who was in between. VK: You mean from media? FC: Everything is a medium, I mean, is the middle. Whereas painting, poetry, music is like sex. Either you do it yourself or you don't. It is. It's a biological expression, it's like a tail on a monkey, like a wing on a parrot. Either you grow your own wings or you don't. So my inclination goes to first-hand knowledge. Whoever can come to me with his own wings, with his own tail, with his own horns, I appreciate, am grateful. Who comes to me with a telephone book or a price list of horns, tails and wings, I care a little less. I have pity and human sympathy for it, but it doesn't give me joy. VK: What about the exteriors of places, because you've lived in a lot of different places, and yet your work to me always has a very interior feeling. It always feels like it's inside a room, or even inside somebody's head, or inside a body. What do you get from the physical exteriors that you surround yourself by, whether they be in India or New York? How do they affect you? FC: That was one of the earliest strategies of the work, was to give the same weight to what's interior and what's exterior, and to consider the body as the line dividing the exterior from the interior. So the line of the drawing is a continuation of the line of the body and also what's inside you overflows outside and what's outside overflows inside. So what is outside of you has an emotional valence, and what's inside you has objective valence also. Definitely, in the same way you can be sad or happy or lonely or whatever, the exterior world too has different emotional colors. Each country, each city, each hour of the day has a diverse emotional sound, emotional color. VK: You once said in an interview that you use the self-portrait a lot because our own body is something we all have experience of. I was wondering if it also is related to a certain kind of skepticism about what can be known -- that you wanted to really pull it in. FC: Well, if the face is a mask, no, a persona, that means that the face reminds you of what is constant in your consciousness, but also reminds you of what is not constant. I mean, it reminds you of the fact that you keep dying and being born again, and again, and again. The consciousness of the self is not always there. It just comes up in flashes, and I guess to meditate on your face means to meditate on this continuous transition we go through, which we are not aware of, or we dislike to be aware of, because it's frightening. VK: But can you point to a reason why in your recent work you've moved away from that, or moved towards other imagery, you've expanded the imagery. Is there strategy to that, or is that just an unconscious process? FC: Well, there is also a weight you want to give to your own work. You don't want your own work to become a signature ever, and you just -- one moves away from everybody. If someone says, "Oh, that's the way you are," you say, "No, no, I'm not like that," and you just move away. So I guess it's a temporary reaction to an acceptance. VK: Speaking of the repetition of imagery -- using the self-portrait, but also say your series of very sexy imagery that keeps repeating over and over again -- when I interviewed Louise Bourgeois, she said that all her work is about the same thing. It's an obsession about her childhood. Do you work through a certain type of imagery that then you finish and move on to another series, or is it more abstract than that? FC: It's a common passion for ritual. Ritual is a function of human life. The context we live in has decided that we don't need ritual, but we do. I am lucky enough to be able to restore ritual into my life. But one of the key elements of ritual is repetition, to repeat an action, and to contemplate the change of meaning that the slight variance in what you do creates. VK: It sounds like it might be a more contemplative process than what Louise was describing. I mean she described it in very violent terms. Like a kind of a rise and a fall. She would be very violent, she'd work on her art, and then feel a big release afterwards. It sounds like what you're talking about is more steady, over time. FC: Fear is involved in it. I mean, you experience some sort of sacred fear before you enter into these grounds, as you should. Because you have to leave the shelter of the persona behind you, you have to leave the shelter of the self behind momentarily. And you are afraid either not to be able to do that or you are afraid to be able to do that. Either way is a fearful situation. VK: Fear of failure and fear of success. FC: Well, yeah, either way there is a fear. Fear of not being able to enter and fear of entering. VK: How important is it for you to collaborate with craftsmen, as in the woodcut of yours that was printed by an ancient process in China? FC: In India also, I've worked with miniature painters on two occasions, and I've never shared the mystique of the signature at the bottom of the work. I think most of the history of painting is a collective history. To restore that situation even for a brief moment in your life, where you're working with many people on something, and you're able to accept all the unexpected, it's a great training. Then to accept also the unexpected that can come out of your own self. VK: I wanted to ask you about material, because you've done fresco, and you started out doing a lot of drawing. You must get some impact off of the material itself. But is that the inspiration for a work or just a corollary? FC: It's the context. Painters in previous traditional societies, they were given a reason to paint and an audience. Painters after the Industrial Revolution are not given a reason to paint, and they are not given an audience, so they have to invent all of these other extensions of the work for themselves. One of them can be traditional materials, which have been always there, always used, and you find yourself almost like an actor impersonating the fresco painter, the bronze caster, the draftsman. It's a way of making yourself believe that you can do what you can do. VK: Any plans to make a film? That seems to be the mode these days. FC: Film is the art of our time, because our time is sentimental and film is sentimental, where sentimental means the history of the persona, the history of the mask, the history of what is always there in someone. The cross on your shoulder, you know the big, heavy bag on your shoulder, like in that Bunuel film. My inclination is more for another sensibility where the persona is not so heavy and not so important. I don't feel the fascination for the mask or the identity, for all the games that various identities are locked in, to meet each other. And I don't think one can make a film without that. Also, photography and film are really so much like the cult of death. I mean, it's really the momentum or the shadow. It's a celebration of death. I do not want to celebrate death. I am an enemy of death. VK: What do you mean by an enemy of death? FC: That painting is still. Painting doesn't move and doesn't play the game. It's something that just sits still and lets death go by. |

|||