|

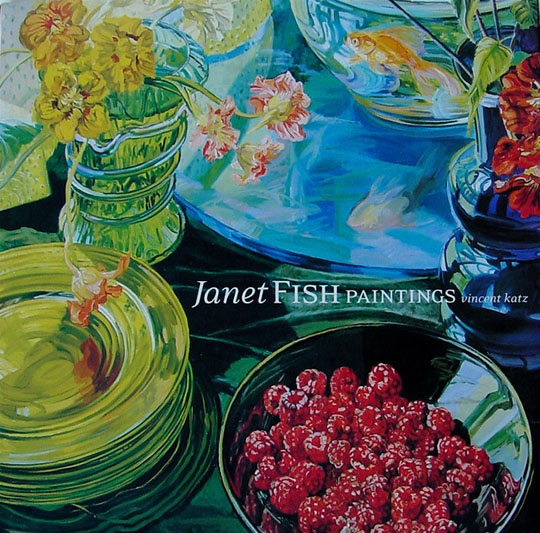

Janet Fish

by Vincent Katz

I

It was perhaps not unexpected that Janet Fish should end up a fine artist. After all, her mother’s father was the American Impressionist Clark Voorhees, and her uncle, also Clark Voorhees, was a sculptor. In fact, Fish did not need to look beyond her immediate family to witness the daily presence of art. Her mother, Florence Whistler Fish, is a sculptor and potter, and her father, Peter Stuyvesant Fish, taught art history at Roxbury High School in Boston, where Fish was born on May 18, 1938.

Fish spent part of her childhood in Bermuda. Armed with that knowledge, one imagines one sees memories of aqua waters and vermilion bourganvillas in her paintings. The only possible impediment was an “authoritarian” father, who, for instance, forbade any music but classical to be played within his household. Her father, in fact, may have been a key to Fish’s artistic success, as she has been rebelling against authority ever since.

While in high school in Bermuda, Fish wanted to be a sculptor. She made sculptures in the styles of Henry Moore and Alexander Calder, inspired by what she knew of the lifestyle of her uncle and also by her experience assisting Byllee Lang, an art instructor who was making sculptures for the Episcopal Cathedral. Members of a steel band posed for the figures and practiced in Lang’s studio, which was a meeting point for artists. Fish was particularly attracted by the idea that people could get by making art, living their lives as they chose.

Because her father did not want her attending art school, Fish studied art at Smith College in Massachusetts, earning her B.A. there in 1960, but in retrospect she has reservations about the teaching of art in academic environments:

University art departments are usually run by the art history departments, and to have any validity, there has to be a lot of talk around it. I majored in something called “Practical Art” at Smith, which meant that I did a lot of studio but also a lot of art history. Smith, as it turned out, actually had a very good art history department and a very good library, which I didn’t realize until I got to Yale. The painting at Yale was better, but the art library at Smith was better.1

The main problem with the academic environment was its lack of rapport with what contemporary artists were doing. An exhibition of new art that came to Smith was roundly dismissed in a lecture by one of the instructors, while Fish remembers being particularly attracted to a sculpture in the exhibition by Lee Bontecou.

The feeling of separation was alleviated somewhat when Fish began studying art at Yale University, where she ultimately was awarded an M.F.A. in 1963. At the Yale School of Art and Architecture, Fish studied with Alex Katz, Philip Pearlstein, George Schuyler, Si Sillman, and Esteban Vicente. Her fellow students included Robert Berlind, Chuck Close, Rackstraw Downes, Nancy Graves, Sylvia Mangold, Brice Marden (?), Richard Serra, and Harriet Shorr. Still wanting to be a sculptor, Fish began studying the Bauhaus-inspired program of Josef Albers, who headed the art department.

Fish seems never to have been taken with pure design, abstracted from observable data, so she switched from sculpture to painting. Many Yale students were mesmerized by the Abstract Expressionists and working in the manner of de Kooning. “I learned all kinds of things to think about when making abstract paintings,” she says, “such as maintaining the picture plane and ‘push, pull.’ Finally, I was sitting there trying to paint these pictures, and I felt no connection to the painting. What I was doing was arranging paint... Abstract Expressionism didn’t mean anything to me. It was a set of rules.”2 Fish cites Mondrian, George Sugarman, and Myron Stout as abstract artists whose work showed ways out of expressionism. She was also looking at Fairfield Porter’s paintings.

Porter had been instrumental in the 1950s as a bridge between what he called objective and non-objective painting. As a critic who was one of the first to champion de Kooning and a painter who dared to paint figuratively in the face of abstraction’s enshrinement as institutional art, Porter was a key questioner of dogma. He wrote in 1960, “Non-objective painting is more graphic and emotional than open to sensation; and realist painting is less interested in nature than in ideas, as: what is natural, or what should painting be about?”3

Porter brings up an interesting question about subject matter. Always one for the pithy paradox, Porter elsewhere claims that subject matters immensely to the non-objective American painters of his era, while it matters little to the objective painters that interest him. Painters like Nell Blaine, Jane Freilicher, Paul Georges, Katz, Larry Rivers, and others had digested the pictorial and technical lessons of abstraction and chose to take a different path. In many cases, taking for subjects the people and things closest to hand, they intentionally deflated the significance of what they painted, while stressing how they arrived at the painting.

Even though Porter and others had punctured the balloon of abstract Modern art’s sometimes self-aggrandizing pretension, the Hegelian idea of progress in art -- that each new phase permanently obliterates the possibility of the previous one -- did not go away immediately. In the 1960s, when Janet Fish got out of art school and moved to New York to become a professional painter, the leading theory was dominated by abstraction’s successors -- Pop Art, Minimalism, Performance, Earth Art, Conceptualism. While attentive to those movements, and in her own way, sometimes paralleling them, Fish determined her own path.

In a talk given in 1973, entitled “What The Sixties Meant To Me,” Rackstraw Downes writes:

I recall in art school being embarrassed by how to paint some tiny slivers of spandrels formed by a circle that was tangent to a square. Katz, my teacher, told me: “develop those forms.” I bought some little sable brushes and poked about. Katz looked at it a week later and said -- at a distance of 10 feet -- “you faked it.” I take that to have been my first lesson in painting as opposed to aesthetics. About this time I saw one painting each by Porter and Katz in an exhibition in the Yale Art Gallery (1961). Full of historicist expectations, I had no idea how to react. I dismissed it as rubbish. But Janet Fish said to me, “You’re quite wrong. This is the latest thing that nobody can stand.”4

While still at Yale, Fish spent the summer of 1962 at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, where she studied with Elmer Bischoff, and Katz came to critique. Skowhegan, partially because it is located in the Maine woods, has always encouraged artists to look at their surroundings, and Fish stopped painting abstract and began painting landscapes. She also became interested in the work of Bay Area painter David Parks, who along with cohort Richard Diebenkorn, was painting the figure using the language of abstraction. That winter, Fish began to paint what would become her defining project -- the still life -- although she probably did not see it that way at the time. Fish’s career can be summed up as the revitalization of the still life genre, no mean feat when one considers that still life has often been considered the lowest type of objective painting.

In 1963, Fish married painter Rackstraw Downes (who would later edit Porter’s collection of criticism), and they spent the summer in Maine. “I did a bunch of landscapes in Maine,” she explains. “Rackstraw was still doing abstract paintings, and I was painting little landscapes with acrylic, painting factories and things around Belfast. In the winter, I couldn’t do that any more, and I started doing still lifes.” A new life was about to begin.

II

The problem of determining one’s subject, of finding something to paint with which one can become completely involved, is the artist’s primary problem. Proceeding is also complicated, once the artist has found her subject. The problems are just beginning, but they are problems of a different sort. They are sometimes technical, sometimes visual, sometimes poetic, but they are not philosophical. The artist has found her basis, and no one can shake her from that. Finding that basis can be a devastating experience for some; it takes great reserves of self-reliance and will.

The main difficulty is the need to wrench oneself from the influence of those artists of the previous generation that one admires. Those artists, who may be friends and contemporaries of the younger artist, are what is current and real. To say that one will not be like them is almost a disavowal. Not knowing in which direction to turn, and living with the possibility that, unlike those happy predecessors, one’s own decisions may turn out to be completely misguided, the position of the young artist trying something different is one of instability. A few sympathetic friends can be a help.

After a year in Philadelphia, Fish moved to New York in 1965. At that time, Downes had been asked to exhibit with a group of abstract artists who published a statement to go along with the exhibition, to the effect that painting “in the middle 1960s must be abstract, flat, and made of pure colors.” Downes thought, “I can’t sign this. My wife is a realist painter.” He added a head and tail to a snakelike figure in one of his paintings, and that was the end of his abstract career.

Downes kept returning to Maine and began figuring out how to paint the landscape there. Fish became more enamored of what she saw as the solidity of objects on a table. It would be a long time before the landscape would again penetrate her perspective. Having had no training at Yale in painting from life, she had to find out for herself how to approach it. The lack of a system, however, may in some cases be likened to the lack of a straitjacket. Fish could look at the problem of painting fruit and vegetables on a table with fresh eyes and intelligence.

I was discovering things I didn’t know when I just stared straight at something. Once I’d been painting for a while and looking at something for a while, I started to see what I didn’t know was there originally. In the way it looked. Then I would try to define that through paint, what I was seeing, and interpret it. I would be quite surprised after a while at what was there. As I was painting more, if I was excited about something that I was looking at, I began to try not to figure that out in advance. If I did have that positive feeling, it usually meant to trust that unconscious thinking that there was more there than I could initially verbalize. It would mean there was a lot there to look at.

Her earliest attempts to come up with a new type of painting, surprisingly, do not rely on the primacy of the stroke. In the ‘40s and ‘50s, Jackson Pollock had elegantly emphasized the importance of the artist’s handiwork. No one could follow Pollock, though, in his particular technique, without looking sycophantic. Willem de Kooning, on the other hand, did offer an avenue to succeeding artists, in that they could take his example of the independent brushstroke and bend it to varying uses, both objective and non-objective. The objective painters of the 1950s usually employed a certain brushiness that competed effectively for attention with the images they made.

In the 1960s, hot became transmuted to cool, and the importance of personal expression that the brushstroke represented grew less. Hard-edge abstraction came to the fore, and Pop soon removed most traces of the artist’s personal touch. Realism, too, was moving towards more enclosed forms. Pearlstein, Katz, John Button, Jack Beal, and others began painting figures and objects with unbroken lines that smoothly enclosed the shapes they surrounded. The trick for those painters, as for Fish, was twofold. It was for the paint to retain its vitality and for the forms to have volume. Photo Realism and Pop were two styles in the 1960s that did neither.

When Fish moved to New York, among other odd jobs, such as answering Pen Pal letters, she worked in an art store, where she could get paint at discount. It was then that she became involved with paint as substance and also began to learn about color. Albers’ color exercises, which she had done at Yale, were about pure, composed, colors and their relationships. Important, but it had little to do with the wetness, texture, translucency, and combinatory dynamics of oil paint. These are the raw materials with which a painter works, the real matter of a painting.

Fish has said, “I tried to decide how what I was seeing related to the ideas I had brought from abstraction. I got a lot of energy from looking at different kinds of paintings and reworking the ideas that I saw there.”5 It was an exciting moment, a moment of analysis and decision. From abstraction, Fish was pulling simplification of form. Myron Stout and Albers himself were working with unadorned forms, organic on the one hand, geometric on the other. Fish chose items of daily use, foodstuffs, and found in them simple units with complicated surfaces and volumes.

The strange thing about paintings like Yellow Bananas (1967, 40 x 46 inches) and Small Red Pepper (1968, 20 x 20 inches) is that they look like they were painted in the 1960s. Even though they depict fruits and a vegetable in isolation, they reveal something about how those things were seen in those days. That has partially to do with the extreme close-up viewpoint Fish chose, something to do with the plainness of the severely limited backgrounds. There are no lush tablecloths or Persian spreads casually draped over exquisite furniture, on which these items rest. On the contrary, but for the occasional shadow indicating a table plane, they could be floating in space. We never see the edge of the surface, and in these early paintings the surface is usually a variation on off-white, giving a contemporaneous feel of the light and furniture of an artist’s loft.

What started as self-education, through persistent effort and thought, soon led a new style of painting:

At first, they were like landscape, things designed to create space. It almost started as an exercise that I’d given myself -- to paint some solid objects, because I felt I wasn’t dealing with them properly. Then I began to start to define painting in them. I took a reductive approach, which was really what was in the air anyway. So I started taking out and taking out, to find what really did interest me. Then I started throwing these apples on the table, just painting them as they were. And then I started to expand them in size, because I decided it wasn’t what was around them that I was interested in. It was what was happening in the form. So I started to enlarge those things and make them be the whole focus.

In their frontality and simplification, these mid-’60s paintings of Fish’s bear a similarity to the huge iconic heads being painted by her Yale classmate Chuck Close. Both artists were finding alternatives to expressionism in the blunt, tightly framed, focus on a single, centralized image. A comparison can even be made to the late-’60s work of Brice Marden and Richard Serra. All these artists, in distinct ways, were using a reductive approach, in which a maximum of effort could be subsumed into a highly simplified final image.

In a conversation with Fish, Close remembers how aesthetic ideas in the 1960s could travel across party lines, so to speak, and that, while they and others were painting representations, they were doing so in a way that was cognizant and approving of current tendencies: “I was making representational painting, but the things that influenced people who were involved with Minimal concerns or Process stuff were in the air. Ideas such as paring stuff away... trying to impose limitations that would allow one to move or change... were not the sole property of the Minimal artist or the Process group.”6

Fish responds to Close by saying, “...what I’ve always liked about New York was that you could visit studios and begin to relate to what someone was doing by seeing the process.” In 1968, Fish was a founding member Ours Gallery, an artists’ co-operative gallery on Grand Street, and had her first one-person show there. She showed the close-up fruits and vegetables and a new body of work she had begun, fruits and vegetables in the plastic-wrapped packages in which one bought them. She enjoyed being part of a collective force, whose interests ranged across realism, abstraction, assemblage, and other forms.

In 1970, after Ours Gallery closed, Fish joined another artists’ co-op, 55 Mercer, where she had another exhibition, this time featuring the plastic-wrapped packages. She was moving from an interest in volumes depicted by areas of light on objects to a more fleeting sensation of light reflecting off and through transparent plastic. She had set herself a more difficult challenge, while simultaneously using more identifiably contemporary subject matter.

At about the same time Fish was zeroing in on produce, Jim Dine, after having focused on tools, was undergoing a similar fixation with turnips, lettuce, and carrots. Dine’s efforts, some of which turned up on a record cover for the English band Cream, were more about drawing than about observed situation and light, as was the case with Fish. Her package paintings always have that compelling tug between realism and modernism (played out in the physicality of the abstract forms delineated, particularly, by reflections of sky and window mullions on the irregularly stretched plastic).

The art dealer Jill Kornblee saw Fish’s show at 55 Mercer. The next year, 1971, she invited Fish to show at her gallery. It was Fish’s first exhibition at a commercial gallery. Her painting had also moved to a new level. With a painting like Two Boxes Lemons A&P (1971), Fish achieves greater dexterity than previously in the various textures of plastic packing frame, crinkly plastic wrap, and the puckery skins of the citruses. Also, there is a jump in scale. From the beginning, Fish had pushed her humble subjects into the viewer’s space by extreme focus and large scale, but at three by six feet, Fish’s picture of lemons makes them seem gargantuan, yet oddly mundane at the same time.

In the seventies, Fish changed from things lying down to things standing up. Instead of fruits or packages that seemed thrown down randomly, or at least lay on a table awaiting inspection, she now painted bottles and other containers that projected upward from a surface. Verticality became a motif, as did clustering, eventually aligning itself, at least in the artist’s mind, into what she calls the grid. She was aware of the modular thinking of such artists as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and others, and their formal repetition influenced her choices of subject.

What is surprisingly not the case is any approximation to what Andy Warhol had done in the previous decade in terms of turning an observed object into a cultural sign. Despite the brand-name labels on bottles of gin, Windex, and olive oil Fish painted, there is little sense that a social observation is intended. The labels simply become part of the visual environment; particularly of interest to Fish are the colors engendered by labels prismed through glass and liquid.

In Majorska’s Vodka (1971), Fish is again working with extreme close-up, as in the fruit paintings. The large, five-by-four foot, scale, combined with the tight cropping, makes the five bottles, pushed close together, seem monumental. In her looking, Fish focuses on aspects of the packaging intended to make the product seem appealing -- bottle shape, label design, material of bottle screw-cap -- and carefully finds painted ways to capture them on canvas. There is a fascination with those items -- booze, Windex, honey -- that one consumes, but in Fish’s case that fascination gets translated into an inquiry into appearance.

In her first paintings of glass surfaces, Fish has found what will excite her for many years to come, albeit with increasing variety and complexity. The objects in her paintings almost become fetishes for her. As she becomes entranced by what she sees in their physical make-up, her victory is twofold: she has found something completely engrossing, and she has a subject which will challenge her technical skills to the utmost. Painting liquid, glass, the reflections seen through various bottles grouped together -- there can be few more difficult tasks the painter can set herself.

The passage of time also began to become central to Fish’s work, the way daylight passing over and through objects changes slightly over a period of even a few minutes. The discipline of fastidious observation that became more and more important to Fish allowed her to find a dramatic component to her subjects, namely a changing light.

Basically I’d be painting what I saw, but light is always moving through things. Part of the reason I’ve always set things up in light is that it always keeps you right there in the moment with everything moving and changing all the time with no time to fall asleep. And then all of a sudden something exciting would happen in one place, and I’d paint that. It wouldn’t be particularly the objects. It might have been a flash of light.

Windex Bottles (1971, 50 x 30 inches) presented a different challenge in that the liquid was not clear but blue, and Fish rose to the challenge combining numerous tones of blue, sometimes using individuated brushstrokes, other times more of stain-like blend, always creating the impression that light is coming through the liquid in the plastic bottles. The sensation of light in the background and shadow on the sides of the screw-caps and plunger facing the viewer is unforgettable. Fish was fascinated by more than the effect of light. She wryly interprets the characteristic pinched-waist shape of the Windex bottle as a female icon, created by male manufacturers to appeal to female buyers. One does not need to know this to appreciate Fish’s portrait of the three bottles, but their erectness is figurative, as noted earlier, and they can be seen as a humorous take on the three graces motif favored by many classical male artists and viewers.

A series of paintings of honey and jelly jars goes to the farthest extreme of probing the grid as found in everyday, non-rectilinear, objects. She sets various identically shaped jars together on a surface and starkly limits the canvas shape to the edges of those shapes. Florida Jellies, which shows six squat jars arrayed on a surface, is thus 20 by 70 inches. An additional element characterizes this 1972 work -- the detailed reflections of a set of windows facing the jellies. More than in previous reflective surfaces, Fish here is showing details of the room in which these jellies were painted, and doing so in a playful way, that brings to mind the detailed precision of the Dutch painters of still lifes and interiors. Fish’s work will move more in that direction in years to come.

More and more, as the 1970s progressed, it became apparent that Modernism’s hold on the thoughts of the art public, including collectors and museum curators, was beginning to weaken. The once-powerful idea that each way of making art permanently displaces those before it began to have its doubters. Rauschenberg had painted his white paintings in the early 1950s after all. Artists had denied the canvas since the early 1960s, exploring non-commercial avenues of performance and other time-based work. It began to dawn: what does one do after one has already done the ultimate? By the end of the 1970s, younger artists, who came of age too late to hold the Modernist masters in unquestioned awe, decided that doing what they wanted was most important, and many were seduced by painting’s eternal lures.

In the meantime, Fish, Close and others of their generation had been consistently moving painting towards an incarnation that was distinct from what had come before. In terms of career, there began to be more opportunities. From the first, fledgling attempts of the artists’ cooperatives in the 1960s, serious commercial galleries began to appreciate the value of the new objective painting. Fish showed with Kornblee Gallery in 1971 and 1976, the same year she also showed with Phyllis Kind Gallery, which was promoting the New Imagist painters in Chicago. In 1978, Fish had her first exhibition with the Robert Miller Gallery, where she would remain for over a decade. That marked Fish’s arrival as a major figure on the contemporary art scene.

In 1973 and 1974, Fish taught summers at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and began to add to her paintings elements of landscape perceived through glasses of water she set on window sills. While still seen through the screens of reflection and liquid, these landscapes are significant as being the earliest examples of Fish’s allowing the world beyond her chosen objects to impinge on her subjects. A 1976 painting, F.W.F. (72 x 56 inches) is one of the most impressive of this era. The patterns created by the complex forms of the glasses, compounded by the reflective surfaces on which and in front of which they sit, engender a profusion of detail that is new for Fish. Differences in depth of field become more pronounced, as do differences in precision and looseness of technique. Every area of the canvas has visual interest, and many focal points attract the eye in succession. Not only her powers of observation but Fish’s powers of presentation, of painting technique, have grown greater and more diverse.

As though one is observing a performance, one is tempted to linger over this piece, witnessing one, then another, tiny explosion of painted brilliance. One can find many pictures within this picture. To call those areas ‘’abstract” is to miss the point, which is that this is plainly a picture of glassware of a particular nature. The painting says, “This is what glassware does when seen in such a light.” That it may shock the viewer is all to the good. There is an additional level of meaning to the painting, determined by the title, which comes from the initials one can see inscribed on two of the tall goblets in it. They are the initials of Florence Whistler Fish, the painter’s mother. Just as, in the future, Fish will more and more include in her paintings objects and ultimately people of personal significance to her, so will she allow her pictorial field of vision to expand accordingly.

In 1975, Fish was able to buy a loft on Prince Street, in Manhattan’s SoHo, in the same building in which Chuck Close was living. For the first time in New York, Fish had vistas of buildings and distances that intrigued her. It was time to leave the world of iconic jars and bottles, a world she had discovered on her own and which now felt safe, as well as exciting. Despite its attractions, she knew she could not continue in that same vein indefinitely.

At different times, I’ve had a crisis of light, feeling that I had plumbed the depths of some place where I was, and I was feeling that way. When I moved to Prince Street, there were all the buildings out the window. Before, I had not wanted to suggest any other world than the world of the object. Then I really did need to move, so I thought I’d let other elements in, and at first I got really negative reactions from my friends and other people, even some collectors. They thought it was a big mistake. I remember this collector just cornering me at a Whitney opening and telling me how much he hated what I was doing. But you have to do what you have to do. I thought that would be best, so I started to add things in, first by putting buildings with the glass objects, and I was starting to look at different shapes.

Fish’s paintings were changing. August and the Red Glass (1976, 72 x 60 inches) moves away from simplicity of water in clear glasses. The variety of colored glasses in this piece accentuates the varying depths (unlike the frieze of Florida Jellies and other earlier pieces, which concentrated objects in a shallow space). By increments, Fish is allowing more illusion of depth into spaces, and at the same time she is adding more detail. The crimson glass at the top left starts a diagonal to the pink glass at lower right, with the crimson echoed near the center of the canvas via the reflection in a third glass. Meanwhile, an opposing diagonal is set up, from the blue glass at upper right (with its concomitant reflection on the mirrored surface below) to a blue reflection at lower left. It should be noted that the angle of the blue diagonal is less extreme than that of the red diagonal, the variety adding formal interest to the visual play. Fish has long been concerned with having the eye move through the painting by varying paths, and by the mid-1970s, she is readily achieving this goal. She has referred to this as a “revolving composition: your eye goes to one end of the picture and then revolves back through the painting in a different way.”7

August and the Red Glass is complex in other ways as well. The glance of the observer is observable this time, striking the plane on which the glasses rest at a slightly oblique angle. As in F.W.F., there is an interplay between areas of pure color (the reflections) and passages of architectonic precision (the rounded and rectilinear ridges of a goblet). That this precision may remind us of architecture is not at all fortuitous. When we look to the top edge of the canvas, a final bit of patterning reveals itself in the rectilinear grid of shadows cast by a fire-escape (not visible) falling on the building opposite. Simultaneously, Fish was able literally to paint a grid (instead of alluding to one as she had done in earlier work) and also to allow the dimension of the outside world, of landscape, into her work.

continued

|