Painting Maine: A Look At Artists’ Interpretations of the Maine Landscape

by Vincent Katz

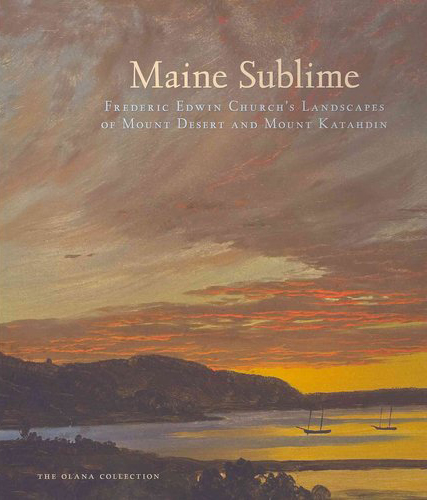

People have always been drawn to the region now known as Maine. They have been summoned by Maine’s natural beauty, its verdant lushness — even in winter — its clear light, and its plentiful fauna, both on land and in the waters. Regarding painting, and in relation to thinking about Frederic Edwin Church’s paintings of Maine, it is worthwhile to compare some approaches that followed his. In terms of subject matter, style, and technique, later painters tackled the Maine experience with a variety of approaches, incorporating innovations of their times or making innovations themselves.

Winslow Homer (1836–1910) was based, for the last twenty-seven years of his life, at Prout’s Neck, Maine, where he created enduring images of northern waves pounding massive boulders. Whereas Church was more drawn to the open serenity of Maine’s inland skies, Homer attempted to fix in paint moments in the midst of terrific explosions of energy at the coast. The coast itself is symbolic of the border between relative stability and the dangerously pulsating, unfixed, rhythms of the places one must go in order to survive, to earn one’s living, and in a larger sense to move to the next phase in life. Homer’s images contain this symbolism, and his way of painting conveys those borderline emotions.

Some of Homer’s Maine seascapes, such as Breaking Storm, Coast of Maine (The Art Institute of Chicago), an 1894 watercolor, possess an air reminiscent of Church’s oil on paper Sunset, Bar Harbor, 1854(see fig. 39). In both cases, an area at the lower right of the image portrays a calm extension of the water’s plane, reflecting dying afternoon sunlight, which has the effect of bathing that plane in a light-hued monochrome. The point of view of the observer in each is slightly different — that of the Church is more elevated — but there is an even greater difference in the emotional tone of each painting. Where the Church is painted with his characteristic delicate precision, the Homer has a wildness to the depiction that suits the meaning of the piece, which is the calm before the storm. Homer’s attraction to instability goes much farther than even that example. He reveled in the actual, bounding, crash of the ocean, as evinced in his 1887 watercolor Prout’s Neck, Breaking Wave(fig. I). Here, he devotes the entire right-hand portion of his image to the foaming wave, and the result is remarkable, considering that watercolor, despite its name, is quite a dry technique. Oil paint is a medium more conducive to portraying water, and Homer made good use of it as well. He gives a foothold at the lower left of Prout’s Neck, Breaking Wave, where he uses a more precise line to describe boulders lining the shore, in contrast to the rewet, blotted, and scraped surface of the gargantuan waves and imposing gray sky.

One can discern a link between Homer’s paintings of the Maine coast and those of Edward Hopper (1882–1967), mainly in the way each man characterized the juncture of sea and land, with its implications for men whose livelihoods depended on assaying the hazardous deep. Whereas Homer tends to be more narrative, giving the viewer details of fishermen’s travails and dangers, Hopper is more concerned with painterly effects, in attempts to convey the light, air, and surfaces of the rock and grass he sees. Later, Hopper develops a metaphoric level to his work, particularly in his series, done in the late 1920s, of watercolors and oil paintings of Maine lighthouses, in which the difficulties of living on the sea are alluded to, while the formal elements effected by his cropped views of vernacular architecture give his work a distinctly modern tone.

Marsden Hartley (1877–1943) was not drawn to Maine. Rather, he was born there, in Lewiston, and during the first decade of the twentieth century devoted part of each year to painting there. His life and career were spent alternately denying and embracing this heritage. In the 1910s, he worked mainly in Germany and France, and in an essay written in 1918, he stated, “Something must take the place of the America, of New England, in all our ways, esthetically speaking.” Like many artists of his generation, he went to New Mexico, and then he went back to Europe. In the late 1920s, he returned to New England, where he complained of the “commercialism of the nouveau riche. . . . I shall be happy enough to get out of New England never to enter it again.” Yet, finally, in 1937, he decided to return to Maine to live, and he was based there for the rest of his years. It could be argued that he painted some of his most significant works during this time, taking inspiration not only from coastal life, but also from the woods and lives of those in the interior of the state.

Unlike his contemporary John Marin (1870–1953), also long associated with Maine, who used the landscape more as a ground for modernist compositions, Hartley sought the cataclysmic stories of the common man testing his strength against the elements. In Northern Seascape, Off the Banks, 1936–37 (Milwaukee Art Museum), which Hartley painted in Nova Scotia just before moving back to Maine, the principal subject is the battering of waves on shore rocks. He makes these waves into physical objects, at least as solid as the rocks. Solid, too, are the great triangular clouds in the sky, outlined in white. Hartley seems to be equating these natural elements of wave, rock, and cloud, endowing them all with stability, while man is dwarfed, his presence represented by two sailboats, small in comparison to the natural elements and caught between them, with only a narrow path to ply between wave-battered rocks and heavy, descending clouds. Many of his Maine seascapes present the sea in similarly elemental terms.

Hartley reveled in the strangeness, too, of the regional experience in Maine. Abundance, 1939–40 (fig. II) is an odd image. A picture of logs being floated down a river, it has an almost geometric, two-dimensional, abstract effect. And yet, in the brutal economic realism of the place and time, Hartley creates an unexpected image of wood as plenty, as nourishment.

Fairfield Porter (1907–1975) came from the Midwest, but his family had ties to Maine and in fact owned a small island, Great Spruce Head Island, in Penobscot Bay. The siblings shared the island, with Fairfield’s family inheriting the Big House his father had built. Over the years, Porter painted many defining images at Great Spruce Head Island. He painted trails and paths on the island, but he is most known for sun-soaked images of the Maine grasses and conifers leading down to seaweed-laden rocks. One can almost smell the air in Porter’s paintings. Another type of painting he did in Maine is reminiscent of work he did at his winter home in Southampton, Long Island. In these works, Porter painted family and friends inside the Big House, often on the screened-in porch, where he was able to expand upon the fascinating senses of interior and exterior he admired in the paintings of Vuillard.

In this brief survey, we have been able to see how different generations of artists responded to Maine, using their own versions of the art of their time to reinterpret familiar visual elements. Hartley’s 1941 painting of Mount Katahdin (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.), for instance, is much more cropped than Church’s expansive vistas (see figs. 60 and 66), and Hartley treats the landmass as a hulking darkness, as distinct from Church’s more nuanced tonal, approach. Porter, influenced by Vuillard’s use of static marks within realistic compositions, as well as by Willem de Kooning’s powerful dynamics of paint handling, attempted to meld these approaches in images that were intentionally familial and domestic (fig. III). Alex Katz also responded to earlier artists’ achievements and expanded on them in his images of Maine (fig. IV).

Katz (born 1927) first went to Maine as a student at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1949, and it was then that he discovered his predilection for direct painting from life. While he would later transfer this type of painting to urban subjects, he began in the countryside in Maine, and he continues to this day to spend every summer there, in Lincolnville, looking for new ways to envision the landscape. Techniques for renewing the idea of landscape have included the turbulent use of visible brushstrokes in the early work, details of clothing, buildings, furniture, and cars that pinpoint a contemporary time and place, and, since the 1980s, large-scale paintings that wrap around the viewer, creating what the artist calls “environmental” paintings. Another important element, underlying all of these, is an appreciation and use of abstraction, whether it be a solid bank of color, standing in for a sky, or a field of flowers whose all-over energy was inspired by the paintings of Jackson Pollock.

Lois Dodd (b. 1927) began spending summers in Lincolnville in 1954, later buying a place in Cushing, and she has come back to Maine every summer since. Her Maine paintings, including close-up views of windows of farmhouses, doubling as mirrors, and moonlit landscapes, have gained acclaim for their individual vision.

Many other artists have come to Maine since and worked with its particular landscape as subject matter. Neil Welliver (1929–2005) was born in Pennsylvania and moved to Lincolnville, becoming identified with the state because of his paintings of the Maine woods. He intentionally used artificial-seeming colors, claiming that he was not interested in painting from nature. His paint handling often seems perfunctory, yet his imagery is personal. Rudy Burckhardt (1914–1999) bought a house in Montville, not far from Lincolnville, joining the growing artists’ enclave there. His first summer in the Lincolnville area, Burckhardt rented a house with his wife, the painter Yvonne Jacquette (b. 1934), the poet and critic Edwin Denby (1903–1983), and painters Red Grooms (b. 1937) and Mimi Gross (b. 1940). The summer of 1964, they all collaborated on a film entitled Lurk, based on the novel Frankenstein. Further summers resulted in further film collaborations, often with visiting poet, dancer, and painter friends, photographs and paintings by Burckhardt, and Jacquette’s developing explorations of aerial views, many of them done by renting small planes and flying over local towns. Painter Rackstraw Downes(b. 1939) had a place not far from Lincolnville in the 1970s, and it was there that he began to develop his defining wide-angle format, as well as a taste for subjects such as that portrayed in his 1986 painting Dragon Cement Plant, Thomaston, Me.: The Rock-Crushing Operation(United Missouri Bank Collection). We have come a long way from Church’s Romantic visions of a pristine nature surrounding Mt. Katahdin; surely artists in the future will find other ways of representing Maine’s singular vistas.