home | books | poetry | plays | translations | online | criticism | video | collaboration | press | calendar | bio

| Art Books and Catalogues | Curatorial | Poetry | Translation |

|

|||

|

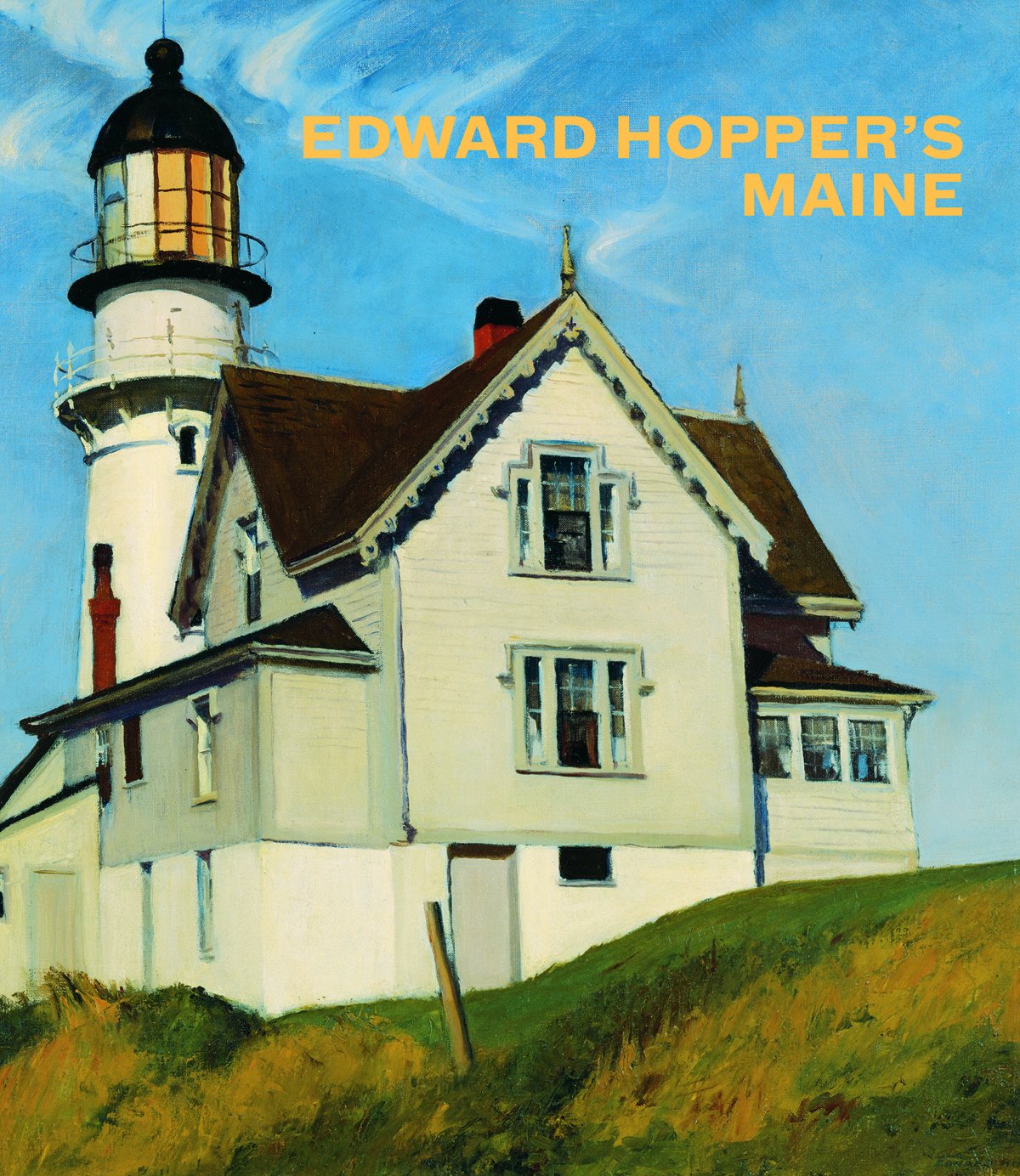

___EDWARD HOPPER’S MAINE, (2011, Prestel Publishing) |

|||

|

Mastering The Vernacular: The Role Of Maine In Edward Hopper’s Early Work by Vincent Katz Maine was in some senses an intermediary experience for Edward Hopper. Not so much in terms of chronology, but rather stylistically, Maine lay between France, where Hopper achieved his first intimations of a new image, and New York, where he found the subjects to create some of his most iconic paintings. Although he may have made his defining works elsewhere, however, we can find vital clues in his Maine work as to how he saw and experienced the visual world. Hopper’s first stint in Maine was in the mid-teens of the twentieth century, when he was in his thirties; at that time, he painted in Ogunquit and Monhegan. The second was about ten years later, when he worked in Rockland, Portland, and Cape Elizabeth. In the earlier period he did many small oils on canvas, wood, and board, while in the later period he dedicated himself primarily to watercolor. On his trips to Europe, particularly in France, Hopper had learned to master oil painting technique and also discovered his inclination for empty spaces, sharply defined by abrupt angles and radical cropping. One can see this clearly in [Steps in Paris] (1906, oil on wood, 15 x 9 ¼ inches, Whitney), which suggests a photographic awareness in its cropping, the view restricted to the steps’ steep ascension, with only the barest details lining those steps. Yet, the details — including a handrail, a balustrade, and a bit of statuary in the distance — are precise, conveying a particular place, time period, time of day and weather. Hopper would by and large follow the same approach in his mature work. Unusual compositions, as in the 1909 painting in which river boats jockey for primacy with the fanciful structure of the Pavillon de Flore, already begin to dominate. In some works, such as Canal at Charenton (1907, oil on canvas, 23 ¼ x 28 ¼ inches, Whitney) and Canal Lock at Charenton (1907, oil on canvas, 23 ¼ x 28 5/8 inches, Whitney), one can observe the deliberate use of the brush stroke as a carrier of semantic force, particularly in depictions of leaves and the textures of grey skies. In the summer of 1912, working in Gloucester, Massachusetts, Hopper chose to paint houses, sailboats, masts, and rocks. He also made a seascape, Briar Neck, Gloucester (1912, oil on canvas, 24 x 29 inches, Whitney), which, apart from some sails in the distance, is devoid of the evidence of human presence. According to the catalogue raisonné, Hopper later told Lloyd Goodrich that this was the first plein-air painting he did Stateside. In 1914, and again in 1915, Hopper spent the summers in Ogunquit, Maine, where he made a number of oil paintings, many of them seascapes of the type he began in Briar Neck, Gloucester. Often, Hopper was going down to the seashore and trying to capture in oils the light, the air, the moving water and sky. These challenges are represented physically in the rough patches of paint Hopper used to depict to his subjects. Although the results can seem more improvisatory than in paintings in which Hopper evoked a still emptiness, on the other hand, the bravado of the handling shows he was still experimenting with how paint could function. The Dories, Ogunquit, although dull in its edges, is bright in tonality. Cove at Ogunquit was painted with an assured confidence. Its composition, taking something from Hopper’s Paris days, seems deliberate in its contrast of shadowy foreground with brightly lit middle and background. Rocks and Houses, Ogunquit, makes use of an unusual composition, with a strange, hulking landmass and flowering weed occupying the foreground, while a group of small, bright, buildings lies clustered behind them. The most singular piece, in the context of the others he created that summer, but conversely the one most like what we might associate with mature Hopper, is Road in Maine. Here, the particular notes of the telephone poles lining the road anchor the image in one’s memory in a definably Hopperian manner. The empty road carries the symbolic function that train tracks would in his later work, while the acid greens of the grass cause the picture to pulsate. Hopper began going to Monhegan Island in Maine in 1916 and continued to go there every summer, through 1919. Painting mostly at the coast, Hopper worked freely with his medium. The marks are always distinct, although they also function in the service of the depiction. At Monhegan, Hopper found a working situation conducive to experiments he wished to make in terms of form and color. The colors are often rich and vibrant, and the brushwork makes its presence known. Interpreted through a psychological lens, the deep blues and dark areas can suggest unexplored areas of the unconscious. Through the action of paint, Hopper began to tap into larger cultural spaces. A few paintings delve into other topics, and it is there one can see glimmers of another Hopper lurking behind the summer-colony enthusiasm of the seascapes. One alternative effort is Landscape with Fence and Trees, which is possessed of an intriguing tentativity. It is not a product of the location per se but rather exists as an opportunity for experimentation in technique, with layers of lighter color patches in the tree leaves lying without modulation on top of layers of darker colors. In another piece, Hopper includes a lighthouse, which will become an important symbol in his later Maine watercolors. There is also a fascinating pursuit of a geologic subject — in this case Blackhead in Monhegan, a giant outcropping leading down to the sea that Hopper portrayed over and over, in drawings as well as paintings, an image of Mont-Saint-Victoire-like significance for him. One painting, in particular, catches the eye: Waves Crashing On Rocks, Monhegan. One can perceive several passages of different browns, a tonal approach, in the foreground; the foam of the crashing waves is painted with controlled gestures, while the distant horizon line is delicate and precise. According to the catalogue raisonné, Hopper began to make watercolors in the summer of 1923 in Gloucester, at the encouragement of Josephine Nivison, the future Mrs. Hopper. He had used watercolor for commercial illustrations before that but hardly at all for fine art works. He worked prolifically in watercolor at Gloucester during the summers of 1923 and 1924. There he clearly set forth his vision of the place, with the directness of a photographer. He depicted the Italian and Portuguese quarters; he painted people on the beach in bright light under beach umbrellas; he painted beam trawlers and old Victorian homes. His point of view, where he situates himself physically, is always arresting, as is the way his eye frames his subjects. He worked extensively in these years in watercolor, less frequently in oil. He also made watercolors in New Mexico and in New York, before returning to Maine in the summer of 1926. This time he went to Rockland, where he was engaged again in watercolors, usually devoid of human presence. He painted beam trawlers from odd angles, up close, focusing on their cordage and construction, radically cropping these elements to charge his compositions. He also made watercolors of the Rockland lime quarry, where he found outcroppings that became strange, organic forms in his works. Several of the watercolors reference railroad tracks, a motif that would grow for Hopper in compositional force, sociological import, and philosophic weight. The compositions in the 1926 watercolors are fascinating: how did he decide from precisely which angle, and at what range, to view the beam trawlers he portrayed? There is definitely evidence in these extreme, precise, compositions of Hopper’s awareness of modernist artists, abstract ones like El Lissitzky or Moholy-Nagy as well as representational ones such as Charles Sheeler or Charles Demuth. What these artists share is a sense of meticulousness, of the fine balance of lines and spaces in a composition that almost resembles an architect’s rendering, as opposed to the freer approach to landscape of artists like John Marin or Arthur Dove. In addition to the boats and buildings near the docks, one finds other images attracting Hopper’s attention. Civil War Campground is reminiscent of Road In Maine in its use of the strong lines of telephone poles as compositional elements; it is also an example of Hopper’s interest in the ravages of history. Talbot’s House, with its elaborate Mansard roof, provides a counterpart, both socially and formally, to more hardscrabble structures, such as those depicted in Rockland Harbor. In summer, 1927, Hopper was back in Maine, this time in Two Lights, halfway between Prout’s Neck, where Winslow Homer had painted coastal scenes in 1890s, and Portland. Hopper developed on his work from the previous summer with additional unusual compositions, improving his ability to capture the changeable Maine light. In Two Lights Village, he used a telephone pole’s erratic tilt to signal the modernity of his view of a tiny community directly confronting the implacable elements. This image has a timeless, ancient, feel, while simultaneously being a thoroughly accurate depiction of a contemporary American place. The unfinished Coast Guard Station is useful for the information it provides regarding how Hopper used white paper to reflect Maine’s sun on the sides of buildings and rocks. A singular notion of composition proliferates, as in Hill and Houses, where the current lighthouse captain’s house and lighthouse seem to rise out of the former lighthouse captain’s house. After spending the summer of 1928 in Gloucester and doing numerous watercolors there, Hopper returned in 1929 to Maine. The pictures he did at Two Lights that summer are different from those he did in Rockland in 1926. Instead of the detailed, close-up views of beam trawlers, he was now content to show Coast Guard surfboats at rest and a dory with sailor in the water. He seems to have taken an interest in broader forms and broader subjects. The Dory is even reminiscent of images by Homer. There is more space in his 1929 images, and one senses he wanted to make pictures with a grander sweep now. He did one large, unusual oil, Maine in Fog, during 1926-29. Chronologically, it comes between two other oils: a confident, detailed depiction of a Gloucester street and the classically urbane Automat of 1927. Seen in this context, Maine In Fog makes sense in terms of scale and ambition in what it insists on leaving out. Four oils from this period, done in Maine, indicate how far Hopper had matured as a painter. While their subject matter may not be as defining as that of Hopper’s city works of the 1920s, these four paintings — Lighthouse Hill (1927), Captain Upton’s House (1927), Lighthouse at Two Lights (1929), and Coast Guard Station (1929) — show a mastery of architectural form and scale of composition that is light years away from works from only a few years earlier. In particular, these paintings evince Hopper’s fascination with the forms of the vernacular — architecturally composed in this case — that distinguish his work. Devoid of human presence, they are full of the evidence of human endeavor. They show, in an American style, images from American life. This differentiates them from French painting and from his own small-scale exercises of waves crashing against the shore. From that point on, Hopper would spend his summers in Truro, Massachusetts. The watercolors he did at Truro, like the paintings he made in Maine, serve an important role in the study of Hopper’s work. In both cases, they show him working on technical issues and exploring a visual study of American commonplaces. Beautiful works in themselves, they also have much to say about iconic painter of emptiness. |

|||